| By Taylor Madgett |

“They Done Killed A.C.”: The Death of Justice in Macon

On October 13, 1962, at around 9:30 p.m., seventeen-year-old A.C. Hall left the Middle Georgia Veterans Club in Macon, GA, with his friend Eloise Franklin and began walking to their homes. They stopped in the driveway of the G. W. Carver Elementary School so Franklin could rest her feet. Almost immediately, Macon Police Officers James L. Durden and Josh T. Brown pulled into the driveway, their cruiser’s headlights directed at the pair. Frightened, Hall pleaded with Franklin to run. She refused. Hall then fled the scene on foot alone.[1]

Earlier that evening, officers Durden and Brown had received a call from a couple, Barnett and Doris Hopper, who claimed that an African American man had stolen a .22 caliber pistol from the glove compartment of their car. Doris Hopper reported that she had seen an unfamiliar figure exit the driver’s side door of her husband’s car and walk down the street. At first glance, Doris Hopper thought that her husband had taken the car to the service station and that the man was a mechanic returning the vehicle. When her husband said the car had not been at the service station, the Hoppers rushed outside and discovered that the glove compartment had been opened and his .22-caliber pistol was missing. They called the police.[2]

Durden and Brown responded, proceeded to the couple’s house and asked Doris Hopper if she could identify the suspect. The Hoppers got into the patrol car and joined the officers in searching the neighborhood, including the area surrounding the Carver School. After a short period of time, Officer Brown said, “Well, we’ll check behind the school. It’s doubtful he’s there, but we’ll check anyway.”[3]

As they pulled into the driveway of school, their headlights cast upon Hall and Franklin. “That’s the man!” Mr. Hopper would later recall Doris Hopper exclaiming. [4] She claimed to recognize the suspect by his white shirt and build.[5] As Hall attempted to run, Brown stopped the car and Durden yelled out of the window several times for the young man to halt. Durden fired at Hall from the cruiser window. He would later say he thought Hall was reaching in his pocket for a gun. Durden got out of the police car and shot at Hall again. Officer Brown also fired a number of shots in Hall’s direction. Durden then chased Hall down a path behind the school and down a nearby street to a point where the young man collapsed under a streetlight. Hall rolled over and sat up. Durden ordered him to raise his hands. Hall raised his hands in surrender and then fell over backwards, mortally wounded.[6] Franklin, who had trailed the officers during their pursuit, arrived at the scene, saw Hall on the ground, and exclaimed, “They done killed A.C.!”[7]

The police shooting was one of innumerable incidents in the Jim Crow South in which African Americans were abused and killed by white, southern police officers. Unlike many other cases of police misconduct and brutality against African Americans in the Jim Crow South, however, both officers were suspended pending an investigation.

On October 17, 1962, a five-man, all-white coroner’s jury, which was charged by the coroner to investigate the cause of the victim’s death, convened to hear the circumstances surrounding Hall’s death.[8] Under questioning from Assistant Solicitor General J. J. Gautier, pathologist and Bibb County Medical Examiner Dr. Leonard Campbell testified to the cause of Hall’s death. Campbell had performed the autopsy on Hall’s body and determined that a bullet had entered the left side of Hall’s back, traveled a circuitous route through his left lung, diaphragm, spleen, and liver, then exited the upper region of the chest. “Death,” Campbell concluded, “was due to gunshot wound of the chest.”[9]

The officers offered their testimony to the coroner’s jury in unsworn statements. Durden recalled that they had received a report that “a colored fellow” had stolen a pistol. During their canvass of the area with the Hoppers, they encountered Hall on the side of the school, they told the coroner’s jury, and pursued Hall after he ran. Durden testified that he observed Hall with his hand in his pocket and that he fired his own weapon when Hall turned on the officers. Brown, the other officer, offered a similar account in his unsworn statement. After stopping the car, he said, Hall had turned towards the officers. “I pulled out my gun and held it to the left side,” Brown said. “I was shooting to the left side, just pulling the trigger fast as I could pull it because whenever he turned, first thing that popped in my mind was the danger that we was in and Mr. and Mrs. Hopper was in the car with us.”[10]

The officers described how they pursued Hall around the back of the school and to the corner of Ash and First Streets where the wounded man collapsed and then attempted to surrender to the police. After calling an ambulance to assist Hall and after securing the scene, the officers searched the area for a weapon. “We didn’t find the gun,” Brown reported in an unsworn statement to the coroner’s jury.[11] Indeed, it took officers until the next morning, as Officer A. M. Huffman testified, to find a gun. He recalled that he had located a .22 caliber pistol during a search of the grass bordering the path down which Hall fled and checked it into evidence at the City Hall. Mr. Hopper testified, however, that the gun the police officers found did not match the weapon that the couple had reported missing the previous evening.[12]

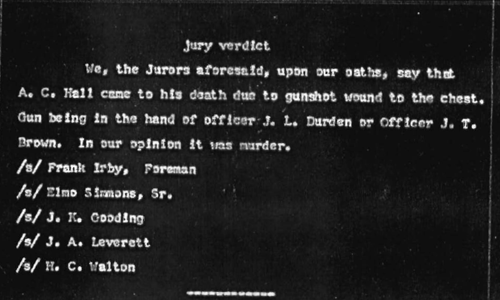

At the end of the inquest, the coroner’s jury determined that the wounds Hall suffered had indeed come from one of the officers’ pistols, though the jury was not able to determine which officer fired the fatal shot. It was rare for all-white panels in the Jim Crow South to find that white police officers had acted excessively, much less murderously, in investigating and apprehending a black suspect. In this case however, the coroner’s jury concluded, “In our opinion, it was murder.”[13]

At the end of the inquest, the coroner’s jury determined that the wounds Hall suffered had indeed come from one of the officers’ pistols, though the jury was not able to determine which officer fired the fatal shot. It was rare for all-white panels in the Jim Crow South to find that white police officers had acted excessively, much less murderously, in investigating and apprehending a black suspect. In this case however, the coroner’s jury concluded, “In our opinion, it was murder.”[13]

The coroner’s inquest’s responsibility extended only to determining the cause of Hall’s death; the coroner’s jury had no authority to bring criminal charges against the officers. Local law enforcement officers could arrest the officers and take them into custody – and they did, based on the inquest; the officers were freed after posting $3,000 bond – but only a grand jury and a prosecutor could charge them with murder.

Still, the jury’s conclusion was so startling and uncharacteristic that it was widely misinterpreted in African-American newspapers. “Two Macon Police Charged With Murder In Slaying of Youth, 17,” said an erroneous front-page headline in the Atlanta Daily World. “JURY CHARGES 2 GA. COPS MURDERED BOY,’ the Chicago Defender said in its headline. The Pittsburgh Courier went even further: “White Jury Convicts Dixie Cops of Murder.”[14] But the grand jury, when it met in early November, had a different idea. In very short order, it met and decided against indicting the officers for the death of Hall. Police Chief L. B. McCallum re-instated the officers on November 11.[15]

Hall’s death was one of a number of incidents in the Macon area in eighteen months that spurred local protests against racial segregation and discrimination. Located approximately eighty miles southeast of Atlanta, Macon is positioned almost dead center in the state’s Black Belt, a region ripe with urban civil rights agitation in the post-World War II era—particularly surrounding voter registration campaigns, desegregation, and equal opportunity in government jobs—and occasional Ku Klux Klan retaliatory violence.[16] The day of the coroner’s jury, William Randall, the head of the Bibb Coordinating Committee, led 3,000 protestors on a march on the town center, three and four abreast, wearing black bands of mourning representing, in Randall’s words, “the death of justice in Macon.” They also carried placards reading, “Stop this senseless killing.” Local authorities allowed the march to proceed despite a city ordinance forbidding such activities. Unlike civil rights protests in nearby Albany, local authorities adopted an “attitude of non-intervention” and the march unfolded in an orderly manner.[17]

As the holiday season approached, community leaders formally announced plans for a citywide boycott of local businesses in an effort to get the officers’ suspension reinstated. At an overflow meeting at the Beulah Baptist Church, between 500 and 800 members of the community signed petitions demanding suspension of the officers. Randall reserved special condemnation for the grand jury: “Those 22 men who refused the other day to indict those cops knew, too, it was murder.”[18] Local organizers also reached out to Atlanta civil rights attorneys Donald L. Hollowell and Howard Moore, Jr. with a request to represent Hall’s mother in an attempt to prepare another case for the grand jury. They planned to request the appointment of Hollowell as a special solicitor general so that he could assist the state in presenting another case to the grand jury, which was scheduled to convene in February.

Over a hundred members of Macon’s African American community presented the petition to the City Council at the end of November and urged the body to take action against the police. They then officially launched an economic boycott against local businesses. The Council referred the petition to the Police Aid Traffic Committee. A majority of the committee denied the charges against the officers however and refused a proposal by two members of the body to censure the officers.[19]

The protests of the black community did not produce the desired results. The officers returned to duty and were never tried for the killing of A.C. Hall.[20]

— Edited by Brett Gadsden and Hank Klibanoff

“Negro March Protests Dixie Cop Shooting,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1962;

“Murder Charged to Ga. Cops,” Chicago Daily Defender, October 23, 1962.

On white on black violence, see Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, (New York: Vintage, 1999), 253.

Chicago Defender, Oct. 23, 1962, 1;

Pittsburgh Courier, Oct. 27, 1962, 23.

“Angry Macon Negroes Launch Huge Boycott,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 1, 1962.

Andrew Manis, Macon Black and White: An Unutterable Separation in the American Century (Macon: Mercer University Press, 2004), 157, 210.

“Negro March Protests Dixie Cop Shooting,” Chicago Tribune, October 18, 1962;

“Murder Charged to Ga. Cops,” Chicago Daily Defender, October 23, 1962;

“Jail Two Policeman in Slaying of Boy 17,” Call and Post, November 2, 1962.