| By Lauren Browning |

On Thursday October 29, 1970, the front page of The Dawson News greeted its readers with the stunning news that the police chief, Weyman Burchle Cherry, had died instantly the previous Saturday when his car crashed into the abutment of a railroad underpass. The crash had injured his two passengers, his friend Jerry Thurmond and Thurmond’s wife Lois.[1] At the age of 44, he was described as a husband, father, friend, coach, and prominent local figurehead. Known as ‘Cherry,’ he coached Little League baseball and “Midget Football” and was praised as a constant presence at all local sporting events.[2] Chief Cherry’s influence within the Dawson community was clearly evident at his memorial service. Members of the Dawson City Council served as pallbearers, while officers from multiple counties formed an escort in honor of their deceased colleague.[3] The Dawson News reported in Cherry’s obituary that he “was instrumental in preserving law and order in the community.”[4] He had served Dawson as a police officer for four years and as chief for 10 years; to many he was a local hero and model citizen.

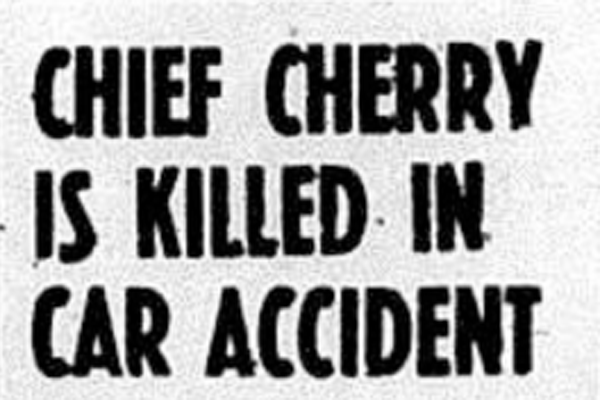

Headline from the Dawson News announcing the death of Police Chief Weyman Cherry, The Dawson News October 29, 1970.

But not everybody felt that way. Black citizens of Dawson saw him as a hateful, cruel monster. “W.B. Cherry had steely eyes, a menacing look, and virtually every black in Terrell County feared him because of his long list of atrocities against blacks,”[5] Alan Bradley Schrade, a history graduate student who later won a Pulitzer Prize as a newspaper reporter, wrote in his 1995 masters thesis about Terrell county.

Cherry operated in a Jim Crow culture that gave law enforcement officers a sense of immunity in responding violently against blacks. By his own admission, Cherry had killed two people when he was a police officer and, in a month’s span, beat one Dawson citizen and shot another.[6] Cherry could walk the streets of Dawson as two men, one as a beloved local hero, the other as a feared and hateful white policeman.

Born in 1926, Cherry grew up in the Jim Crow South. In 1945 he enlisted in the U.S. Army for one year. He was 19 years old at the time and only had three years of high school education.[7] Before joining the Dawson Police Department in 1955, he had worked at an auto parts store in Albany and had never done any police work.[8] He fit Gunnar Myrdal’s description, in An American Dilemma, of Southern law enforcers: “The typical Southern policeman is thus a low-paid and dependent man, with usually little general education or special police schooling. His social status is low.”[9] The minimal qualifications necessary to be considered a police officer in the Jim Crow South gave considerable power to an otherwise lowly regarded white citizen. “Almost anyone on the outside of the penitentiary who weighs enough and is not blind or cripple can be considered as a police candidate,” Myrdal wrote, adopting language provided by a contributor to An American Dilemma, notable sociologist Arthur F. Raper.[10] At the trial brought about by Hattie Bell Brazier’s lawsuit regarding her husband’s death, Cherry admitted that it was not until four years into his law enforcement career that he received any sort of formal training.[11]

In the Jim Crow South, policemen were just slightly above blacks in the social “caste system” while they simultaneously acted as the ultimate enforcers of white supremacy. “This weak man with his strong weapons—backed by all the authority of white society—is now sent to be the white law in the Negro neighborhood,” Myrdal wrote.[12]

On April 20, 1958, when James Brazier was driving through Dawson in his new Chevrolet Impala and came upon Officer McDonald trying to force his father, Odell Brazier, into the police car, the younger Brazier demanded that McDonald stop hitting his father and offered to help get his father into the police car peacefully.[13] In the Jim Crow Guide to the U.S.A., Stetson Kennedy explained that under the dictates of racist etiquette, many blacks lost their lives by talking back to whites.[14]

In his trial testimony, McDonald stated that he was a plain patrolman while Cherry, as the acting assistant chief at the time of Brazier’s 1958 arrest, held more authority.[15] After a mere three years of police service and no formal training, Cherry had risen to the ranks of assistant police chief. As a patrolman, Cherry earned a modest salary of $200 a month[16] while Brazier earned $300 per month working multiple jobs.[17]

Cherry had expressed disgust at what he believed was Brazier’s ability to own new Chevrolets in 1956 and again in 1958. In November 1957, Cherry had arrested James Brazier on a speeding charge. “You smart son-of-a-bitch,” Cherry said to Brazier at the time, according to a statement Brazier’s wife Hattie later gave investigators for the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. “I been wanting to get my hands on you for a long time…You is a nigger who is buying new cars and we can’t hardly live. I’ll get you yet.”[18] Cherry also hit Brazier on the head, she said.

Cherry’s actions imply an existing hatred and vendetta toward Brazier as well as clear abuse of police powers. His actions were reflected in Stetson Kennedy’s assessment of white reaction to black displays of financial comfort. “Your race may be judged quite as much by the etiquette you employ [in the Jim Crow South] as by the physical characteristics you manifest…(if you look black, but act white), needless to say, only gives rise to homicidal tendencies in the Southern white community.”[19]

In his deposition, under questioning by Hattie Brazier’s attorney, Donald Hollowell, Cherry explained why he did not shoot James Brazier on April 20, 1958: “Because I had no reason to shoot him.”[20] Hollowell continued questioning Cherry:

Hollowell: Well, you’ve shot many other men, haven’t you?

Cherry: If I had reason to, yes.

Hollowell: How many men would you say you have killed altogether?

Cherry: Two.

Cherry identified Willie Countryman as one of his victims. He shot and killed Countryman exactly one month after Brazier’s death[21], but Cherry never clarified the identity of the second person he killed.[22] “[The police officer’s] word must be taken against Negroes without regard for formal legal rules of evidence,” Myrdal wrote, “even when there are additional circumstantial facts supporting the contention of the Negro party.”[23]

Eyewitnesses insisted that when Cherry arrested James Brazier at his home, he used a black jack, containing metal, to beat Brazier and threatened him with his gun before taking him to jail. However, Cherry asserted that he used the less injury-inducing leather slap jack to hit him twice and that he never pulled his gun on Brazier.[24] Brazier entered his cell walking, conscious and clothed. He exited his cell covered in blood, barely conscious, carried by others, and died due to brain injuries on April 25, 1958.[25] Brazier’s words evidently triggered the “homicidal tendencies” Kennedy referred to. Cherry’s brazen debut on the stand suggested that he was not afraid of the repercussions of his actions.

Cherry’s actions shocked the nation but the laws of the Jim Crow South enabled him to continue his violent reign without showing remorse. In an interview with the Brazier family, James Brazier’s sister Sarah talked about how she, as a restaurant worker, had to continue to serve Cherry and other officers involved in her brother’s death, and had to treat them as if nothing happened. James Brazier’s second daughter, Hattie Polite, stated in the same interview, “People were just prejudiced back in those days…I guess they got it from generation to generation…they were just hateful and mean, just had a lot of hate in their heart.”[26]

Edited by Hank Klibanoff