The Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory University is both a class and an ongoing historical and journalistic exploration of the Jim Crow South. Emory undergraduate students are examining Georgia history through the prism of unsolved or unpunished racially-motivated murders that occurred in the state during the modern civil rights era. By using primary evidence – including FBI records, NAACP files, personal archives, family photographs, old newspaper clippings, court transcripts and more – and by immersing themselves in the scholarship of historians, journalists and memoirists, students come to see and understand a history that is little known from the inside looking out and long forgotten from the outside looking in.

The Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory University is both a class and an ongoing historical and journalistic exploration of the Jim Crow South. Emory undergraduate students are examining Georgia history through the prism of unsolved or unpunished racially-motivated murders that occurred in the state during the modern civil rights era. By using primary evidence – including FBI records, NAACP files, personal archives, family photographs, old newspaper clippings, court transcripts and more – and by immersing themselves in the scholarship of historians, journalists and memoirists, students come to see and understand a history that is little known from the inside looking out and long forgotten from the outside looking in.

Taught by Profs. Hank Klibanoff and Brett Gadsden, the civil rights cold cases course is cross-listed in Journalism, History, African-American Studies, and American Studies. As Emory undergraduates have discovered and revealed, James Brazier, Clarence Pickett, Willie Countryman, Lemuel Penn, Hulet Varner Jr., A.C. Hall and others were targeted for death because of their race, beliefs, or civil rights work – or in some cases merely because of what they drove, how they spoke, or the ever-shifting lines of racial etiquette they crossed. In most cases, these murders prompted no state or local investigations or prosecutions, and received inconsistent investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

In Georgia, unrestrained agents of white supremacy, sometimes believing their actions were legitimized by the fiery words of their political leaders, killed and inflicted great injury to untold numbers of African-American men and women between the end of World War II and the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. When the Department of Justice in late 2006 released a list of more than 100 unsolved racially-motivated civil rights-era murder victims in the South, 19 were from Georgia. But that list, which the Justice Department received from the Southern Poverty Law Center, was never seen as being complete; since then, others have come to light. Indeed, Emory students have gathered 50-year old documents that reveal names of many more African-Americans who were killed because of their race during the modern civil rights era.

Emory students have focused their attention less on figuring out who-done-it (because in most cases, the assailants were known) and more on exploring why. Why would white police officers be so offended that a black man owned a nicer car than they could afford that the officers would kill the black man? Why would white physicians, examining black patients who had been brutally beaten by police, so readily conclude the victims were drunk or faking pain and ignore the signs of grave injury, withhold medical treatment, and send the patients home or back to their jail cell to die? Why would a black inmate agree to become the “trusty” to a white sheriff who openly reviled and belittled blacks, knowing his role meant spying on other black inmates and covering up for violent acts by law enforcement officers? After an all-white coroner’s jury’s concluded, based on testimony, that a white police officer murdered a young black man, why would a grand jury refuse to bring charges against the officer? After an all-white grand jury concluded that a white police officer likely murdered a black inmate by beating him to death in a jail cell, why would a trial jury, after only a one day hearing, take less than an hour to find a police officer not guilty?

Our purpose

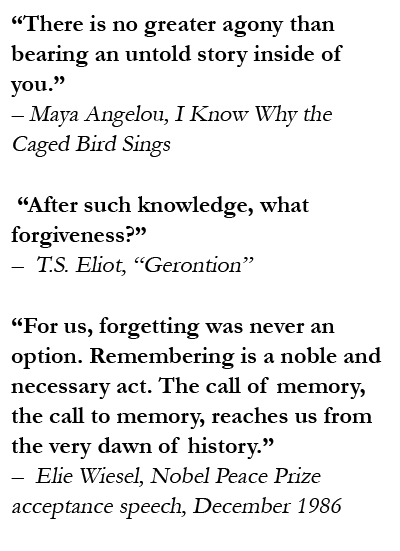

So the purpose of the course and the project is not simply to solve a crime, name perpetrators and push for prosecution. Our purpose is to teach our students how to locate, dig out and analyze the documentation of those crimes, then engage them in understanding the difficult and fascinating (and, for many families, enduring) history of the life and times of these victims. Students are tasked with finding the truth, producing answers that families of victims have long despaired they will never know, and to present accounts of their findings through a public platform that serves to reveal truth, close gaps in history and bring closure to families of victims.

Cold case students in fall 2012 workshop their findings in Brazier case.

More than 50 Emory College students have taken the cold cases course in six semesters since the fall of 2011. The earliest classes focused on the case of Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, who was killed in 1964 as he and two other African-American men drove from Army reserve training at Ft. Benning, Georgia, back to their homes in Washington, D.C. That classes’ essays are being edited for posting on this site. Since then, classes have examined even more extensively the killing of James Brazier in Dawson, Terrell County, in April 1958; you will find those papers on this site now. The latest class has dug into the case of Clarence H. Pickett, who died just before Christmas, 1957, two days after being beaten inside a jail cell in Columbus; those student papers will be edited for this site.