| By Sonam Vashi |

Four days before Christmas in 1957, on a Saturday morning, Clarence Horatious Pickett, a preacher and advertising salesman in Columbus, Georgia, walked into town to pick up his paycheck. About 42 years old and known as “Reverend” to many, the tall, lean man with the mustache and glasses left his home and headed toward The Columbus World, a black newspaper where Pickett worked as a part-time, commissioned advertising salesman.[1]

Before the day was over, Pickett would be arrested, jailed, and beaten senseless by a white police officer, and his injuries would lead to his death two days later. Pickett’s murder would spur a police and FBI investigation where a remarkable number of eyewitnesses would come forward to testify on what they saw. But would an all-white criminal justice system bring charges against a white cop for beating a black man?

Pickett walked to the World, which was located in the same building as another center of black cultural life and identity, the Dixie Theater. Both were owned by Pickett’s longtime friend, Percy L. Taylor, 63.[2]

Pickett had been having some difficulties.[3] He shared his home with his sister, Lillie Banks, who would later say that Pickett had a lengthy arrest record related to his drinking.[4] “He would get drunk and get in jail,” Banks said.[5] Earlier in the year, he had spent six months at the Milledgeville Asylum for “insanity.”[6] After his release from the state hospital in June, he returned to Columbus, resumed his job at the World and was not supposed to drink alcohol.[7] Did he? “Well, he would take him some beer,” Banks said.[8]

After Pickett arrived at the Dixie Theater on December 21, 1957, he called his longtime friend Bessie Smith, 40, and asked her to come pick him up.[9] Pickett called Smith often just to check in with her; she had visited him regularly at Milledgeville. “I have been his personal friend — wherever he goes … he would call me and let me know whether he was all right or not,” she once explained.[10] Bessie Smith brought Pickett’s sister Lillie Banks along. As they arrived at the Dixie, Taylor was about to pay Pickett. But Pickett, for some reason, didn’t want to be paid while the women were there. He showed his displeasure by beginning to talk loudly, and Taylor sensed Pickett did not want his sister to see him getting paid.[11]

Percy L. Taylor, newspaperman in Columbus, was present at Clarence Pickett’s arrest, The Pittsburgh Courier, May 24, 1958.

Pickett had had at least one beer earlier that morning, and while Taylor saw Pickett was not fully drunk, he worried that Pickett might draw police attention and bring new trouble on himself.[12] Taylor had acute memories of another incident that put the black community on edge. Almost two years earlier, local civil rights champion Dr. Thomas Brewer, who had started the NAACP chapter in Columbus and been a driving force in getting federal courts to strike down Georgia’s all-white primary, had been murdered, likely due to his activism.[13]

Brewer’s death had shaken the town’s black community, and Taylor knew to be cautious. So he urged Pickett to go home. Pickett got into Smith’s car but suddenly changed his mind about leaving — Banks thought her brother just wanted to pick up more ads from the newspaper office upstairs.[14] Pickett started getting out of the car just as Taylor attempted to push the door shut to keep Pickett inside.

Columbus Police Officer J. D. Quattlebaum and City Court Investigator Jimmy Scoven were driving by when they noticed the commotion.[15] Quattlebaum got out and walked up to Pickett as Taylor backed away. Quattlebaum and Scoven, both white, would later say they saw Taylor violently forcing Pickett into the car, “hitting him hard” down the front of his body and midsection.[16] Taylor denied ever striking Pickett.[17]

“Reverend, is you — yes, you are drunk again,” Quattlebaum said as he approached Pickett.[18] Pickett insisted he was not drunk, but the patrolman told Pickett to get out of the car and stand up, both Quattlebaum and Smith would later recall. Smith pleaded with the officer to give Pickett a break, so Quattlebaum told Pickett to get back into the car and to go home.[19]

There were other sightings of Pickett that day. Fannie Buckner, 56, later said that Pickett was at her house that afternoon. When asked if Pickett was drunk, she said “she could not tell, as he acted strange since he came back from Milledgeville.”[20]

An hour later, Columbus Police Officers S. D. Wright and Bartow J. Robinson received a call from Malone’s Grocery, where the white, female store manager said a black man had caused a drunken disturbance, cursed and made several “smart remarks.”[21] She directed the officers toward 10th Avenue where they found Pickett, who was almost home and who Robinson recognized from previous arrests. The officers said Pickett was “staggering” on the road and looked disheveled, like he had been in a fight.[22] “I have arrested Pickett before and it is the same thing,” Robinson said.[23] When they brought him back to the police station, one of them wrote down a description of the official charge against him: “Plain drunk.”[24]

As the officers brought Pickett in, police switchboard operator Ruby Welch watched and, she later said, saw Officer B.J. Robinson strike Pickett, who walked “bent over” afterward.[25] His bond set at $12, Pickett was placed in Tank #1, a cell for drunks, by Officers Wright and Joseph Eugene Cameron, a 31-year-old former Marine with a stout, heavy build, an eighth grade education and a receding hairline.[26] Robert Nelson, a white inmate located across the hall in the main windowed inmate area called the “run-around,” saw that Pickett was walking on his own and did not appear drunk as he was brought into the cell.[27]

After being locked up, Pickett began cursing and shouting, Nelson said. “The sheriff of this County said there would be no god damned head beating as long as he was sheriff,” Nelson reported Pickett saying, adding that Pickett called the police “son-of-a-bitch” and “head beaters.”[28]

As the police and prison trusties began giving the inmates supper around 5 p.m., Pickett yelled at Officer Cameron, “You big son of a bitch, come open this door and let me out. I’ve got the money to pay out,” a black inmate, Charlie Johnson, said.[29] Floyd Clifton, a black prisoner in the run-around who knew well the consequences facing black inmates who insult white police officers in the Jim Crow South, warned Pickett to be quiet. Standing nearby, police officer Cameron, who knew well the rules from the other side of the badge, added, “He don’t know, does he?”[30]

Cameron, as black and white eyewitnesses in the jail would later tell the FBI, proceeded to teach Pickett the consequences of his outburst: Cameron unlocked the drunk tank and went inside, they said, while Pickett backed away from the door.[31] The eyewitnesses reported seeing Cameron shove Pickett against a wall and begin hitting him with his fist around the head and stomach five or six times.[32] Pickett fell to the floor, the onlookers said, and the policeman used his slapjack[33] to hit Pickett around the head and neck twice,[34] kicked and stomped him in the stomach[35] and jumped up and down on his body. “You will be quiet — now, you son-of-a-bitch — now you will be quiet,” Cameron said.[36] Pickett did not fight back nor did he resist Cameron during the beating, the other inmates said.[37]

Four inmates — Clifton, Nelson, Johnson, and Ralph Dudley — saw the fight through the glass in the door of the run-around. “The policeman looked like he was kicking the preacher as hard as he could kick,” Johnson said.[38]

Afterward, Clifton listened as a trusty asked Cameron if he should provide food to Pickett. Cameron replied: “I wouldn’t want to put anything in there for him if he stayed in there 20 years.”[39] Cameron later came to the run-around and gave all of the other prisoners a cigarette.

Cameron provided a different version of what happened in the cell, as well as the outcome. In fact, on two different occasions, he provided two distinctly different versions of what happened.

In his first statement, taken the day of Pickett’s death, Cameron said that when Pickett was brought to the station, he appeared very drunk and belligerent.[40] However, Cameron’s statement said nothing about a fight with Pickett. In his second version, relayed over a week later, Cameron said that Pickett was trying to fight other prisoners in his cell, so Cameron entered the cell to remove the other prisoners from harm. Pickett, he said, grabbed his shirt, and Cameron knocked him down.[41] In Cameron’s account, Pickett fell to the floor and grabbed Cameron’s leg, so Cameron kicked to free himself. Cameron said Pickett was cursing and calling him “a ‘son of a bitch’ and everything else he could think of.”[42] Cameron repeated this version at the trial months later. In both statements, Cameron said he heard Pickett singing in his cell two hours after the incident.[43] Cameron said he assumed that Pickett had “forgotten his troubles” and was happy again.[44]

But inmates said that Cameron had beaten Pickett so badly – he did not move or speak until the next morning, they said — that when Cameron brought another black prisoner into the drunk tank, the new prisoner looked inside and said, “I don’t want to go in. That man’s dead, ain’t he?” Cameron replied, “No, I don’t think so,” and checked to see that Pickett was alive.[45]

Around 6 a.m. on Sunday morning, Police Officers J. B. Forrester and Albert O’Malley moved Pickett to the run-around with the other prisoners.[46] The other inmates watched as Pickett, bent forward, walked slowly, holding on to the bars with one hand and groaning in severe pain.[47] For the rest of the morning, Pickett held a hand to his stomach and moaned, “Those officers should not have done me this way.”[48] Johnson said, “I know you are in pain but you brought it on yourself.” Henry Batts, an inmate who was arrested after Pickett’s beating, said, “That man seems to be in awful pain.” Another prisoner responded, “You would be in pain too if you had taken a beating like Reverend Pickett had.”[49] A police officer gave Pickett some aspirin later in the morning, but it did not seem to help.[50]

Taylor, Pickett’s newspaper boss and friend, and R.C. Edmonds, a doorman who said Pickett was supposed to preach for him at an event that day, arranged to pay Pickett’s $12 bond.[51] Pickett was released from jail around noon on Sunday, and Taylor instructed Jimmy Owens and Albert Carter, two boys who worked at the Dixie Theatre, to pick up Pickett. The boys first took Pickett to the Dixie Theatre, where Pickett told Taylor that his stomach hurt and that he couldn’t walk.[52] The boys then took him home, where they had to physically help him inside and onto his bed.[53]

“Baby, they done killed me,” he told his sister. “I’m dying. A white policeman at the jail came into my cell and kicked and beat me.”[54] She called an ambulance to take them both to the Medical Center at 1 p.m.[55] When they arrived, Banks told hospital clerk Willena Burke about Pickett’s beating, and Burke called the Columbus Police to tell them about Banks’ allegation.[56] Pickett was examined by a medical intern, Dr. John Edgar Harris, but Police Officer A. L. McCrone, who had come from the police headquarters to ask Pickett about the beating, interrupted them.[57] Pickett told McCrone that a white policeman had beaten him. As the interview ended, Dr. Harris walked outside of the room, and Officer McCrone followed, asking what Harris thought about Pickett’s condition. “I definitely think he is putting on,” the doctor replied, McCrone’s police report said.[58]

Dr. Harris reported that Pickett showed “marked anxiety” during the examination, as well as abdominal tenderness and “multiple contusions … but an absence of internal injuries” and no recent evidence of trauma.[59] He determined that “the trauma was not of serious nature”[60] and discharged Pickett after prescribing him 75 milligrams of Demerol, a substantial dose of a narcotic pain reliever, and Empirin, an aspirin.[61]

Pickett died at his home the next day, two days before Christmas. His nephew checked his pulse around 1:30 p.m. and told Banks to call an ambulance, but Pickett was already dead on arrival at the Medical Center.[62] Dr. Joe M. Webber performed the autopsy and found his death to be due to a “massive blow to the abdomen” and “shock and toxemia due to peritonitis, resulting from traumatic rupture of duodenum.”[63] Earlier that morning, Pickett had said to Smith and Banks, “Baby, I am dying. I feel like every breath will be the last. I want you to take care of yourself and the children and do what I told you to do.”[64]

As news of Pickett’s death spread through the town, Nelson, the white inmate eyewitness, asked Cameron, “Aren’t you kinda scared you’ll get in trouble about that Negro?” Nelson told the FBI that Cameron retorted, “No, he waited too long to say anything about it.”[65]

That night, Lillie Banks went to the police headquarters and recounted Pickett’s beating. Captain Clyde R. Adair of the Columbus Police Department immediately began a police investigation, which included collecting witness statements from officers and prisoners.

As the larger Columbus newspaper and TV station reported on Pickett’s death and the investigation over the following week, FBI Special Agent in Charge Jimmy E. Hayes sent a memo about the case to FBI Associate Director Clyde Tolson and began following the case proceedings. With a request from Columbus Police Chief E. S. Moncrieff and Lillie Banks’ attorney Joe Ray, FBI Agents Maurice L. Foshee and Henry L. Burgett began conducting FBI interviews of witnesses of the events.[66] Some black prisoners, including Charlie Johnson, recounted Pickett’s beating to the FBI agents but kept silent when questioned by the police officers.[67]

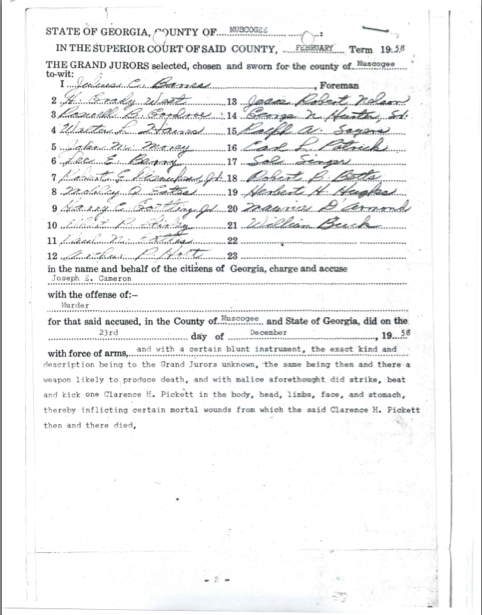

Three days into the new year, 1958, Columbus Police Chief Moncrieff arrested Officer Cameron on charges of murder. Cameron was incarcerated in city jail without bond. As local and state legal action began, Assistant U.S. Attorney Joseph H. Davis requested the FBI to end its investigation and allow state prosecutors to try Cameron as a murder case, rather than a federal civil rights case.[68]

On January 6, a preliminary hearing was held in Recorder’s Court before Judge Frank Girard Jr., and Cameron was charged with murder, suspended from the police department and bound over to the Superior Court of Muscogee County.[69] Two days later, the Coroner’s Hearing, an investigatory inquest to determine a cause of death to justify criminal proceedings, took place. The Coroner’s Jury found that Pickett came to his death as a result of a blow or blows struck by Officer Cameron.[70]

By January 23, the case had caught national attention. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, a black representative from Harlem, visited the FBI and requested an inquiry into the Pickett case. United Press reporter Helen Thomas, Associated Press reporter Jack Adams, and Marie Grebenc of the International News Service also asked the FBI whether it had looked into the Pickett case as an alleged violation of civil rights. The FBI sent information about the case to the reporters and said that it was following the case but authorizing no action at the request of the U.S. Attorney.[71]

On April 23, 1958, exactly four months after Pickett’s death, Officer Cameron was tried for murder in the Superior Court of Muscogee County.[72] Judge J. R. Thompson presided and said the jurors could “find Cameron guilty of murder, involuntary manslaughter, or acquit the officer on the basis of reasonable doubt.”[73]

According to The Columbus Ledger, prosecutor and Solicitor General John Land said that the trial was one of the “‘most distasteful’ tasks he has had as […] prosecutor because it involved another law officer,” and that “the entire Columbus Police Department was under indictment in the public’s eye because of the charge against Cameron.”[74] He added that prisoners were entitled to the protection of the police, and that “The public has got to be reassured this type of thing will not be allowed to exist.”[75]

Three black prisoners — Johnson, Clifton, and Dudley — and one white ex-prisoner, Ralph Nelson, testified as state’s witnesses at the trial that Cameron had beaten Pickett. Nelson added that Cameron had said Pickett “waited too long to tell anyone” about the beating.[76]

Throughout the case, defense attorneys Al Williams and Owen Roberts attempted to prove that the blows that caused Pickett’s death came from someone other than Cameron, especially Taylor during the alleged “scuffle” outside the Dixie. Quattlebaum and Scoven testified about seeing Pickett and Taylor in a “scuffle” earlier that day, although Banks and Smith testified that there were no blows exchanged.[77] Additionally, police switchboard operator Welch was called to testify at the trial about seeing Officer Robinson hit Pickett. This appeared to be an effort to blame Robinson for Pickett’s death — especially convenient, since Robinson had died of a heart attack one week earlier.[78]

Cameron testified, “I don’t think — I know — I didn’t kill him.”[79]

About 90 minutes after the all-white jury started deliberations, it had its decision: Not guilty.[80] Two days later, Cameron was reinstated to the police force.

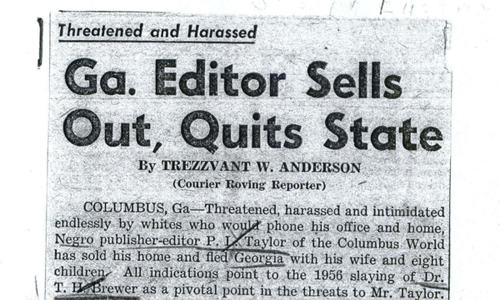

Now, Taylor had lost two friends through brutal means — Dr. Brewer in 1956 and Clarence Pickett in 1957. And just like Dr. Brewer’s surviving family, Taylor sold his home and fled Georgia a few days after the trial, abandoning the town that had again failed to serve justice.[81]

Edited by Hank Klibanoff

Pickett had been selling advertising with Taylor off and on for five or six years.

It was December 21, 1957. Taylor and Pickett had known each other for seven or eight years.

In the months after Dr. Thomas H. Brewer, a black activist who helped found the Columbus chapter of the NAACP, was killed by Luico Flowers in early 1956, Pickett was arrested four times for being drunk. Pickett was arrested 18 times from 1952 to 1957, all on charges involving drunkenness.

Pickett arrived at the Milledgeville Asylum on December 11, 1956, and returned on June 4, 1957.

Smith also visited Pickett every month while he was in the Milledgeville Asylum.

Statement of Bessie Smith to Columbus Police Department, FBI, 12/26/1957, 44-12692.

Taylor said at this point, he suggested paying Pickett later to prevent friction between Pickett and his sister.

Dr. Brewer had openly pushed and raised funds to finance a voting rights lawsuit brought by an African-American man, Primus E. King, against Georgia’s all-white primary. The courts, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, backed the black activists.

“Primus E. King,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/primus-e-king-1900-1986.

Malone’s Grocery store was located at 601 12th Avenue.

Nelson was arrested on 12/19/57 at 8:35 p.m. and was being held for Alabama authorities.

During the Columbus Police Department investigation, Johnson said that he had not seen a fight. When FBI Special Agents Maurice Foshee and Henry Burgett began interviewing witnesses, Johnson then recounted the fight.

Clifton was arrested December 1, 1957 at 1:30 a.m. with Ralph Dudley.

Dudley was arrested on 12/1/57 at 1:30 a.m. with Floyd Clifton.

Dr. Harris died in late 2014 before the Civil Rights Cold Case team was able to interview him. The radiologist who took Pickett’s X-rays was John H. Deaton, who found a “mottled, lucent pattern in right side of abdomen,” which he said probably was fecal matter.

Harris wrote, “Because of: 1) the negative physical and laboratory findings listed in the above examinations; 2) the aprehension (sic) and anxiety shown by the patient during examination not related to the trauma; 3) and because the patient became completely relaxed following examinations (without sedation) and went to sleep on the examining table, it was concluded that the trauma was not of serious nature.”

Pickett was prescribed 75 mg of Demerol and three tablets of Empirin to be taken every four hours. Banks said she was told she could only fill the prescription at the Medical Center. Later that night, Bessie Smith went to Doctor Coffee’s drug store on 8th Street to get a bottle of rubbing alcohol, a bottle of white liniment and a bottle of Milk of Magnesia. Pickett tried eating mushroom soup but as it went down, he jumped up and hollered because he couldn’t take it.

Pickett arrived at the Medical Center around 2:30 p.m.

The request read: “It appears from the facts and circumstances that the charge of murder that has been made is justified and that, therefore, State prosecution should be undertaken. In view of the gravity of the matter it should be handled by State officials in State court as a murder case. Even though, in our opinion, the facts would constitute a misdemeanor violation of the victim’s civil rights in that he was summarily punished without due process. Furthermore, we believe that no further steps, including the filing of charges by the government, should be undertaken until it has been determined what course the State prosecution will take. Furthermore, it is our opinion no further investigation is necessary in this case at this time other than to follow up on State prosecution.”