| By Taylor Madgett, Sonam Vashi, Sanai Meles, Nelson Adams |

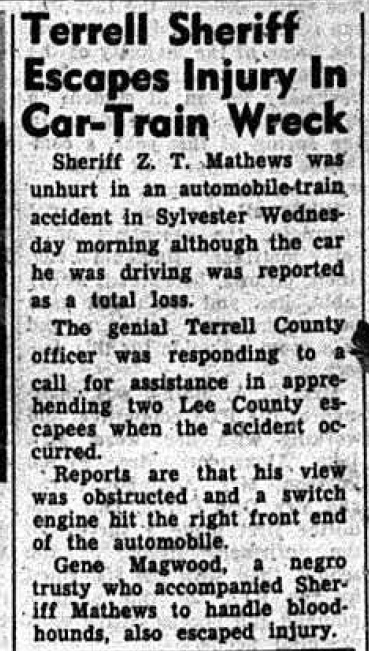

The May 15, 1958, edition of The Dawson News reported upon a seemingly ordinary incident that took place the previous morning: a car accident. The vehicle was completely totaled but its driver, Terrell County Sheriff Z.T. Mathews, survived. The description of Sheriff Mathews’ front-seat companion may have come as a surprise to readers. His passenger, who also survived the crash, was Eugene “Gene” Magwood, a convicted murderer. Magwood was not holding Sheriff Mathews hostage from a kidnapping, nor was he in handcuffs and under arrest. Rather, he had been accompanying Sheriff Mathews on a twenty-mile trip to nearby Lee County to aid in catching two inmates who had escaped from jail. Magwood was a black prisoner at the Terrell County jail who came along in the car to assist the sheriff with handling bloodhounds.[1]

The Dawson News reports on a car accident involving Sherriff Mathews and trusty, Eugene Magwood, The Dawson News, May 15, 1958

On this and many other occasions, Magwood was by Sheriff Mathews’ side to help with any duties.[2] Different from an ordinary prisoner, Magwood was the trusty. As the Terrell County jail’s sole trusty, Magwood was responsible for carrying out numerous tasks and maintaining “order” in the jail, even when—and perhaps especially when—that meant serving as an informer on other inmates. He followed all orders from Sheriff Mathews in return for special privileges, developing a mutually beneficial relationship. On the evening of April 20, 1958, Eugene Magwood performed his role to its fullest, assisting the men who assaulted James Brazier, even though Magwood, like Brazier, was an inmate himself.[3]

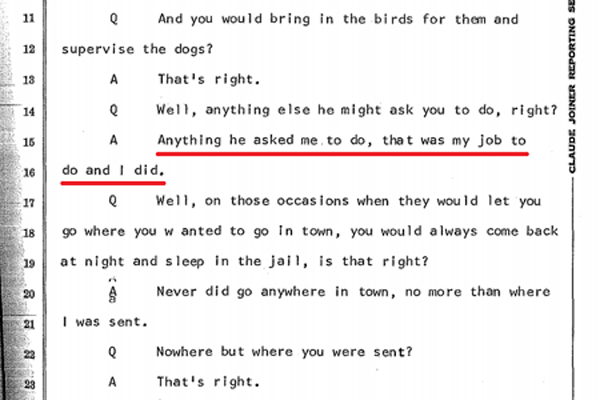

“Anything he asked me to do, that was my job to do and I did.”[4]

On the overcrowded and impoverished penal plantations in the post-Civil War Deep South, prison authorities gave certain inmates, called trusties, operational or custodial responsibilities normally performed by civilian staff.[5] At Mississippi’s Parchman Farm state penitentiary, perhaps the most infamous penal plantation, trusties’ duties included counting inmates, controlling keys to cells or gates, and taking care of bloodhounds. Furthermore, trusties were armed.[6] These unpaid “trusty-shooters” comprised 20 percent of the total prison population and were distinguished from the other prisoners in several ways. In addition to carrying weapons, they dressed differently—wearing vertical stripes instead of the conventional horizontal striped outfit—and lived separately from regular inmates, called “gunmen” (because they “toiled under the guns of the trusties”).[7] No written criteria existed for choosing a trusty, other than prison authorities’ “instinct and observation” of inmates. Many were serving life or extended sentences for violent crimes and so were picked for their ability to intimidate other prisoners.[8] Trusty duties might also include shooting and killing escapees (for which a trusty-shooter might receive “credit in addition to his other good conduct” or even a pardon).[9] Thus, trusties often earned their positions through willingness to use violence to enforce rules.[10]

At the Texas Department of Corrections, where the trusties known as “building tenders” outnumbered legitimate corrections officers, penitentiary authorities rewarded tenders with special privileges, including protection from officers, freedom of movement within (and sometimes outside) the facility, and potentially time subtracted from prison sentences.[11] Since many trusties were serving life sentences, they were motivated by the possibility of reducing a sentence and freedom. Additionally, trusties could hunt, take extended leaves of absence, and even have conjugal visits or the opportunity to visit a prostitute.[12] Because of these privileges, the trusty system created a prison hierarchy, encouraging trusties to inflict brutality against gunmen. Trusties were loyal to prison officials, under the threat of demotion to gunmen status. Consequently, as historian David Oshinsky describes, “Trustees lived a privileged yet tenuous life … determined to please the white men above them, feared and hated by the black men below them.”[13]

Eugene Magwood joined this system in 1955 as a life-sentence inmate after he was found guilty of murder — by cutting — of a man in Ben Hill County.[14] After serving three months on a chain gang in Ben Hill County, Magwood was transferred to serve his remaining time at the Terrell County jail.[15] Upon his arrival to the Terrell County Jail, he almost immediately became the jail’s trusty.[16] Magwood was unpaid but had a number of privileges. Officers sent him on special errands to the store — sometimes allowing him to drive a car — and permitted him to wear civilian clothing such as blue overalls (“the others didn’t wear what I wore,” he mentioned).[17]Magwood even intimated that he was allowed to hunt with his superior officers; in a deposition he described going hunting with Deputy Mansfield Mathews, Sheriff Mathews’ nephew, “a time or two.”[18]

Eugene Magwood described his role as a trusty during a deposition in Brazier v. Cherry, Hattie Brazier v. W.B. Cherry, Randolph E. McDonald and Z.T. Matthews October 10, 1962.

Yet, Magwood’s privileges extended beyond hunting trips and overalls. The only ‘official’ in the jail at night, Magwood, inmates told attorney Donald Hollowell, had sexual access to female prisoners. As Hollowell interviewed witnesses, he learned that Mathews and Magwood apparently divided female inmates; Mathews, Hollowell recorded in his notes, “would handle keys when white women were involved,” and Magwood “handled all work dealing w/ cld men and women,” a reward for his loyalty to Mathews.[19] Prison cook Nettie Cate reported to NAACP field secretary Amos Holmes that Magwood was a constant “encroachment” on Clyde inside her jail cell.[20] While Magwood was not an officer or sheriff, he was an institutional authority in the jail, and his purported sexual advances on Clyde represented the extent of the abuses of power that were propagated by the trusty system.

Eugene Magwood was the trusty on April 20, 1958, the day James Brazier was arrested and brought to the Terrell County jail. Though he would later deny any knowledge or involvement with the events that led to Brazier’s death, other accounts, such as that of Mary Carolyn Clyde, have him interacting with Brazier, even assisting in the beating that led to the death of his fellow inmate.[21] According to the August 1958 account of Mary Carolyn Clyde, Officer Weyman B. Cherry instructed Magwood to take Brazier out of his cell and bring him to the jail yard. An hour and a half later, Officer Randolph McDonald and Magwood carried the unconscious Brazier back to his cell. “He is all right,” Magwood supposedly laughed to Officers Cherry and McDonald, although Brazier was unconscious and unresponsive.[22] According to Clyde’s statement, the next morning Magwood also assisted in dragging the still-unconscious Brazier out of his cell for his court appearance. Yet, when questioned by civil rights attorneys Donald Hollowell and C.B. King during Hattie Belle Brazier’s civil suit trial, Magwood participated in the cover up of Brazier’s murder and evaded revealing incriminating information. Both his deposition and trial testimony were peppered with discrepancies. Magwood repeately dodged Hollowell’s questions by feigning ignorance, mumbling incoherent replies, and giving a multitude of inconsistent statements.

The dramatic difference between the accounts of Magwood and Clyde — and between Magwood’s own statements — suggests that the jail’s authorities scripted Magwood’s testimony during the Brazier trial. In his closing argument, Hollowell tellingly lamented, “What would you think he’s going to say when they brought him here? This was their boy. He would say whatever they wanted him to say; he would say whatever they wanted him.”[23] Eugene Magwood’s loyalties to the jail officials undermined Hattie Brazier’s endeavor to gain justice for her husband and the victims of police brutality in Dawson.

Eugene Magwood’s position as trusty in the Terrell County Jail and in his role in James Brazier’s death provides insight into the complex legacy of race betrayal, victimhood, and collaboration in the era of white supremacy. In “Worse than Slavery:” Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, David Oshinsky likened the situation of trusties to that of plantation slave drivers in the Antebellum South. On large plantations, masters or overseers appointed particular slaves to assist in the running of the plantation by supervising the slaves. In exchange, slave drivers received privileges that were both material, such as extra provisions, and symbolic, such as a sense of authority in a situation in which slaves were stripped of power. Yet, as Oshinsky described, “they too were black slaves and knew that no accomplishment would change their station—the constraints of being black inexorably prevailed.”[24]

In Roll Jordan Roll: The World the Slaves Made, Eugene Genovese described the complex circumstances that drivers had to maneuver within the social fabric of the plantation at their position. The privileges awarded to drivers varied but usually included the likes of extra food, clothing, tobacco, whiskey even cash bonuses of five and ten dollars around Christmas for the most valued of drivers.[25] Yet, such status presented its own set of anxieties. Drivers risked facing alienation and resentment from their fellow slaves at one end of the plantation and their master’s wrath on the other. As historian John Blassingame explained in The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South, “The most diligent slaves were rewarded and pointed to as models for others to emulate. Black drivers were forced on pain of punishment themselves to keep the slaves at their tasks and to flog them for breaking the plantation rules.”[26] Slave drivers walked a “tight rope” between serving the needs of their master and the needs of their slave communities. Blassingame claimed that in many cases slave drivers chose their masters over their fellow slaves. He wrote, “From the perspective of the bondsmen, however, whenever there was conflict in the loyalties the driver acted out his primary role as the master’s man.”[27] [28] Thus, were the benefits and privileges of the position a worthy exchange for the troublesome sense of betrayal and the perpetuation of the system of brutal oppression? It is a question that Eugene Magwood might have pondered throughout his experience as prison trusty.

The figure of the slave driver can help one understand the pull that an advantageous standing may have in an environment, such as the Terrell County jail, where future prospects were grim. The experiences of individuals in the trusty system were similarly characterized by choices and negotiations, privileges and rewards, consequences and concerns, all of which would weigh heavily on the mind of individuals whose decision-making is skewed towards survival. While it would be an ahistorical stretch to equate the experiences of drivers during the Antebellum South with those in the trusty system, they are, nonetheless, positions and institutions rooted in the exploitation of their disempowered people within rigid social orders like the Jim Crow South.

Possibly as a reward for his cooperation and loyalty to the jail’s authorities, Eugene Magwood was released from prison on April 18, 1962, seven years to the day after he began serving a life sentence.[29] According to prison rules, Magwood could earn time off his sentence for good behavior, but Magwood couldn’t have earned enough through the rules to be released after only seven years.[30] Perhaps not coincidently, Magwood was released from the Terrell County jail prior to the Hattie Brazier’s civil suit. The details of Magwood’s post-prison experience and his personal life remain unknown, although it appears he may have had multiple, separate families — one in Dawson and one in Fitzgerald.[31]

In the years following Magwood’s release, the trusty system came under an attack, culminating in Gates v. Collier (1974), in which the United States Supreme Court ruled the trusty system unconstitutional.[32] But, the trusty system existed at the Terrell County Jail for decades after it obstructed justice for James Brazier and his family. A 1995 report on the conditions of the Terrell County jail found the trusty system alive and well more than thirty-five years after the death of James Brazier. [33] The story of James Brazier is emblematic of the multiple, intersecting elements of the injustice that characterized flawed institutions such as the Southern penal system. These institutions exploited vulnerable individuals like Magwood, using like them like pawns to perpetuate racial discrimination and abuse. James Brazier’s murder was a tragedy and its narrative reveals several facets of the larger tragedy that was the Jim Crow South.

— Edited by Danielle Wiggins and Hank Klibanoff

The quote is from a Mississippi official to a Northern delegate at an American Prison Association meeting in 1925.

The crime occurred in Fitzgerald, Ben Hill County, Ga., Magwood’s hometown. Magwood was unable to name the man he had killed.

Regarding Magwood’s position as trusty, Mathews stated: “At all times, he was.”

Magwood remembered hunting with Deputy Mansfield. Nonetheless, during the trial testimony, Magwood would later contradict himself, stating: “No, I don’t remember it.”

Testimony of Eugene Magwood, Brazier v. Cherry, 957.

A few words were left out of my transcription due to difficulty interpreting Hollowell’s handwriting.

Amos Holmes told the FBI that Clyde told Nettie Cate that Magwood had impregnated her, and that the child would be born in August 1958.

Mathews stated: “he can earn 48 days a year; and then he can also earn 24 more days extra good time and I report to Captain Findley his conduct during the time he’s with me each month.”

see Wylene Terry, “Looking for Lost Relatives,” post on Magwood – Family History & Genealogy Message Board, Ancestry.com, May 2, 2000 (11:30 p.m.), http://boards.ancestry.com/surnames.magwood/1/mb.ashx.

This poster is searching for her father from Fitzgerald, Ben Hill County, whose name is Eugene Magwood. Her father had four children with Lula Terry in Dawson, some who were born around 1965 and 1966, after Magwood was released from jail. The poster mentions that she discovered her father had a separate family in Ben Hill County, and that her father died in 1985, when Magwood would have been around 67 years old.

The judge called for “an end to the trusty system, and the hiring of professional guards,” setting legal precedent for its removal throughout the Deep South.

The report stated that prisoners “rely on the inmate trustee for necessary attention,” and that “inmate trustees should not be the sole aid available to inmates.”