| By Ali Chetkof and Scott Schlafer |

Dr. Charles Ward arrived at the Terrell County Jail in Dawson, on Sunday, April 20, 1958, at about 9:30 p.m. to examine a new inmate, James Brazier. Dawson police had requested that he examine Brazier. Ward, who with his medical partner was appointed by the county and city to examine inmates who might need medical attention, met with Brazier in the jail office and delivered a diagnosis that would become consequential over the last four days of Brazier’s life.[1]

Ward would tell the FBI on April 24, when Brazier was still alive, that while he noticed that Brazier had blood in his ear and nose and that he slurred his speech, he suspected only that Brazier was drunk. He saw lacerations and swelling, he told FBI agents, but he saw “no probability of skull fracture.” He told police working at the jail to put Brazier in a cell by himself and to check on him every couple of hours.[2] He did not ask how Brazier came to be injured. “I never ask such questions,” he said. “I had rather not know.”[3]

By allowing Brazier to sleep alone in a cell and not ordering more urgent action, including an X-ray, Ward appears to have neglected medical protocol. According to Emory University pathologist Dr. Mark Allen Edgar,

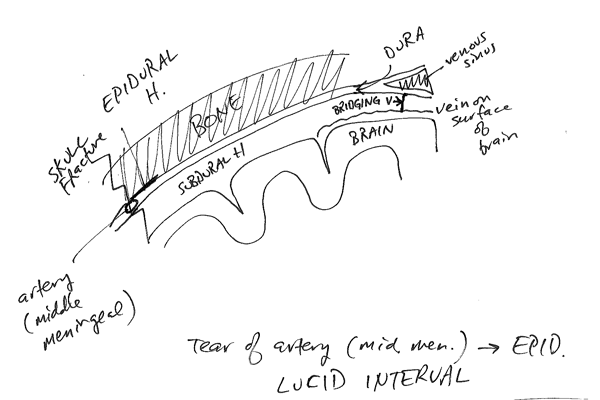

when a patient is bleeding from his ear or nose as a result of blunt force trauma, the doctor should urgently call for X-rays to confirm whether a skull fracture exists. Skull fractures often result in an epidural hematoma, which refers to a ruptured artery leaking blood into the brain’s spatial cavity known as the dura.[4]

Emory University pathologist Dr. Mark Edgar drew this depiction of James Brazier’s injuries, image courtesy Dr. Mark Edgar, Emory University School of Medicine.

Ward’s decision to leave Brazier alone in jail instead of rushing him to the hospital was the first of many instances of doctors’ systematic neglect of Brazier, in all likelihood because he was a black man in the Jim Crow South.

Both of the physicians who would examine Brazier over the next four days failed to properly diagnose Brazier’s injuries, missing opportunities to avert his death. Brazier’s lack of proper medical treatment was common in the South where racial disparity in health care perpetuated inequalities and caused “excess deaths among Blacks.” [5] The fight for racial integration in the South is typically identified with education, voting rights, and public transportation. However, the struggle to overcome discriminatory practices in health care was just as common and important.[6] The Hospital Survey and Construction Act, also known at the Hill-Burton Act, was passed in 1946 to improve the nation’s treatment of black people within hospitals. The grant required hospitals to stop discriminating based on race or color, but allowed them to continue to operate according to the “separate but equal” clause, encouraging racial segregation within the entire health care system and condoning the lack of treatment given to African American patients by white doctors.[7] “Not only were the races to be kept apart in hospitals (including a special section for black infants requiring medical attention), but some denied admission to blacks altogether,” wrote historian Leon Litwack in Trouble in Mind.[8] Because there were so few black physicians, African Americans had to rely on Southern white physicians for their health care.[9] Racial prejudice and discrimination toward black patients led to their poor treatment and, often, poor outcomes.[10]

During his first examination Sunday night, Ward noted Brazier’s unstable health but neglected to make any follow-up appointment to reassess his injuries. Five years later, in his deposition during a civil lawsuit filed by Brazier’s widow, Ward’s story would change in key respects: his diagnosis and his instructions to police on how frequently to check on Brazier. At the deposition, he recalled noting small bruises and cuts around Brazier’s scalp and a likely hemorrhage in his left ear, where he found blood and swelling.[11] “I thought it quite possible that he could have a basal [skull] fracture,” Ward would say in a deposition to attorney Donald Hollowell, who was representing Hattie Brazier, James Brazier’s widow, in a wrongful death civil suit against law enforcement officers. Charles Bloch, a Macon lawyer who represented the two policemen and the sheriff Ms. Brazier was suing, was also present for the deposition. “That’s the reason I instructed them to put him into a cell by himself and to be sure and ‘rouse him at least hourly; and if at any time they could not ‘rouse him, to let me know, because it’s not far to Columbus and that’s the nearest neurosurgeon, and we still had time to get him there.”[12] In his deposition, Ward again said that he dismissed Brazier’s injuries because he believed Brazier’s unsteady gait, slurred speech, and inability to speak coherently could have been caused by “acute alcoholism.”[13]

Brazier’s physical condition seems certain to have worsened after an additional police beating hours after he arrived at the jail. Multiple witnesses claimed that police officers took Brazier out of his jail cell Sunday night or early Monday morning to beat him before returning him to jail — stripped of most of his Sunday suit, bloody and unconscious — around 3:00 Monday morning.[14] Ward said that both times he examined Brazier in jail, he was incoherent and that Brazier’s pupils, while equal in size, reacted to light slowly. However, those symptoms did not cause suspicion, Ward said, because he detected alcohol on Brazier.[15] Ward stated that he did not order that Brazier undergo a blood test for alcohol.[16] Emory’s Dr. Edgar was skeptical that alcohol caused Brazier’s slurred speech. “From six to ten, that’s four hours to get over intoxication,” Edgar said.[17] Edgar also noted it would be hard to know, even with alcohol, that the slurred speech was not connected to neurological damage. Basal fracture symptoms include abnormal eye movements and slurred speech, he said. If the injuries Brazier sustained from the initial beating had not killed him, surely a combination of the two incidents would, Dr. Edgar said; the second beating gave Ward a second opportunity to examine and diagnose Brazier.[18]

But did he? In 1963, five years after Ward examined Brazier in jail, he took the stand to defend his diagnosis and treatment. After state and local law enforcement authorities had failed to investigate the James Brazier murder – that would have meant investigating fellow law enforcement officers – and after a federal grand jury declined to bring charges against the police officers who arrested Brazier, James Brazier’s widow, Hattie Bell Brazier, finally got her day in court. She brought a civil lawsuit against Dawson Police Officers Weyman Cherry and Randolph McDonald and Terrell County Sheriff Z.T. Mathews for the wrongful death of her husband. She was represented by civil rights attorneys Donald Hollowell and C.B. King.

In his trial examination of Dr. Ward, Hollowell zeroed in on Ward’s neglect to treat symptoms of hemorrhage and skull fracture. Hollowell questioned Ward’s treatment of Brazier’s ear. Ward told Hollowell that when he returned to the jail the second time and thus had a second opportunity to check on Brazier’s condition, he never re-checked Brazier’s ear.[19] When asked, as a witness during the 1963 trial, what a normal response would be for a physician noticing a skull fracture in a patient, the medical examiner for Muscogee County (Columbus) who conducted the autopsy, Dr. Joe M. Webber, responded, “…If he was a general practitioner, he would call for a neurosurgeon and let the neurosurgeon take over as soon as possible.”[20] Dr. Ward was a general practitioner. In trial, Ward himself acknowledged that bringing a patient with signs of a hemorrhage to the hospital was a logical course of action. “Well, let’s say, it’s not uncommon practice for a person that we know has a fractured skull to put them in the hospital and observe,” said Ward.[21]

Still, Dr. Ward did not put Brazier in the hospital to be observed. Instead, he told the police officers to put Brazier in a cell by himself, and to wake him either every two hours, according to his FBI testimony, or every hour, according to the later deposition.[22] Dr. Edgar said if he was presented with a patient who probably had been beaten on the head and had blood in his ear, he would recommend the patient be checked far more frequently. “I would probably do every fifteen minutes, I think, with somebody in this situation,” Dr. Edgar stated. In addition, he said, he would urgently check to see if the patient had a skull fracture. “A skull fracture associates with epidural hematoma… and you’d want to be absolutely sure that wasn’t going to happen. So you confirm that there’s a fracture with an X-ray.”[23] However, Ward said he did not recommend an X-ray for James Brazier.[24]

Brazier was taken to the Terrell County hospital on Monday morning only because his wife, Hattie Bell Brazier, panicked upon seeing him at the courthouse slung over in a chair with “white slobber” hanging out of his mouth.[25] Brazier and his wife arrived at the hospital around 10 a.m. on Monday. Mrs. Brazier pulled into the parking lot and frantically asked Dr. Walter Martin, who was sitting on the porch outside the hospital, to take a look at her husband’s condition.[26] Martin, who was Ward’s medical partner, replied, “There ain’t nothing ail the damn nigger but drunk,” and then slammed the hospital door in her face.[27] Ward then took charge of examining Brazier. But first, Mrs. Brazier said later in her deposition, Ward “went in a little room off from where he was and Mr. [Howard] Lee [the police chief] went in there, and they stayed in there talking for so long.”[28] With Brazier’s physical condition quickly deteriorating, either Martin or Ward should have recognized the emergency and given him urgent care and not wasted valuable time. He finally agreed to see Brazier only after Hattie Brazier interrupted Ward’s conversation with Lee and said she was taking her husband to see another physician.

Once Ward finally examined Brazier in the hospital, he quickly determined that the severity of Brazier’s head trauma required the expertise of a neurosurgeon, which Terrell County did not have. It was “quite obvious,” he would later say, that Brazier had intracranial injury.[29] Ward said his main concern was to get Brazier to a neurosurgeon due to his internal head injury. Mrs. Brazier had to then drive her husband more than 60 miles to Columbus, Georgia, to be seen by Dr. John Durden, who specialized in general surgery.

At about 1 p.m., Durden met with and examined Brazier. Durden noted that Brazier “was semi-conscious or irrational and thrashing about from time to time.”[30] Although Ward would later say in his deposition that Brazier was unconscious around 10 a.m., Durden concluded from his examination three hours later that Brazier had gained some degree of consciousness.[31] If Durden had diagnosed Brazier as unconscious, he would have known to operate sooner to increase the chances of Brazier’s survival. Durden would later say he “examined the ears for possible internal bleeding, they showed no evidence of internal bleeding.”[32] Perhaps if Durden had correctly diagnosed Brazier’s level of consciousness and apparent hemorrhage above his left ear, he would have immediately operated on Brazier instead of waiting four hours to perform the surgery.

At 6:05 p.m., about five hours after Brazier arrived at the hospital, Durden performed a craniotomy, removing the portion of Brazier’s skull located above a blood clot, which was then itself removed from the dura.[33] In 1958, there would have been nothing else for Durden to do following the operation other than wait and hope for Brazier’s recovery.[34] Aside from Durden’s neglectful examination and diagnosis of Brazier, his treatment was sufficient and followed medical protocol.[35] Brazier never regained consciousness following the surgery and died Friday, April 25, at 10:22 p.m.[36] The coroner report on April 26, 1958, states that Brazier suffered from a skull fracture and extensive epicranial hemorrhage, causing his death.[37]

Edited by Kate Tuttle and Hank Klibanoff

Dr. Ward would say four years later that he was the County Medical Examiner, appointed by the state and paid on a per-case fee basis. He conducted autopsies but also handled physician duties at the jail with his medical partner, Dr. Walter Martin, who had been named the county physician. “Since he and I work very closely together, his patients are mine and mine are his, and vice versa. If there is a prisoner that they think requires or needs medical attention, we are called and whichever one of us is available goes,” he said.

“A skull fracture associates with epidural hematoma a lot, and you’d want to be absolutely sure that wasn’t going to happen, so you confirm that there’s a fracture with an X-ray,” Edgar said.

An American Health Dilemma covers the various methods of racial discrimination that could be seen in the Jim Crow South’s health care systems. The book noted “the elite, discriminatory, nihilistic, and exclusionary health policies that had the effect of perpetuating inequities, disparities, and excess deaths among Blacks.”(5)

Dr. Edgar said Brazier may have been conscious when Ward visited him in jail because he was in a lucid interval. A lucid interval refers to the period of consciousness between the head injury and the hemorrhage filling the skull with blood. Although Ward reported Brazier as incoherent with slurred speech, in retrospect his health was declining as he was transitioning from a lucid interval to being comatose, and was likely not intoxicated, Edgar said.

The injuries Brazier sustained from his initial beating may have been enough to cause his death, Edgar said. Therefore despite his condition having worsened, Ward should have taken the same precaution Sunday night as he did Monday morning.

Dr. Edgar said a patient with a possible skull fracture should be aroused at least hourly, “I don’t know, I would probably do every fifteen minutes, I think, with somebody in that situation.”

Ward said he did not conduct an X-ray because he said, “…I thought it was quite possible that the blood that I saw was in the tissue of the ear-drum itself.”

Martin was Ward’s associate and both doctors were on call to treat prisoners, depending on which one was available

Mr. Lee was chief of the Dawson Police Department who followed Brazier and his wife to the hospital from the mayor’s court.

After reviewing Brazier’s medical records, Edgar said the surgery was properly performed.