| By Nathaniel Meyersohn |

On September 6, 1966, hours after Atlanta police shot and seriously wounded a black suspected car thief, hundreds of blacks rioted in the area around the newly built Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the $18 million project Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. had supported to lure a major league baseball team to the city. Crying, “Black power!” and decrying “the white bastards!” protestors hurled rocks and bottles and overturned police cars and television trucks. At least fifteen people were injured in the violence, including four policemen. Mayor Allen rushed to the scene and pleaded for calm from atop a police car, but protestors chanted “white devil, white devil!” Police arrested sixty-three people, including Stokely Carmichael, the fiery leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, and other SNCC officials.[1] More than a year after the Selma March drew thousands of supporters to Alabama and the Watts Riots in Los Angeles shocked the nation, and only months after racial tensions escalated in Cleveland and Chicago, Atlanta drew national attention as the latest major city forced to confront urban unrest. The riots stained Atlanta’s well-maintained reputation as the “city too busy to hate,” a model of racial harmony in the South, and particularly alarmed Mayor Allen, whose congressional testimony in support of the 1964 Civil Rights Act helped bolster the city’s progressive national image.

Four days after the riots, William Haywood James, a white 42-year-old carpenter and tree-trimmer, and his wife, Edna Ruth, were driving their 1959 Chevrolet through the Boulevard neighborhood of Atlanta in the early evening.[2] James and his wife were heading south on Boulevard, a predominantly black section of the city’s Old Fourth Ward, while Hulet M. Varner Jr., a sixteen-year-old black teenager, and a few of his friends had gathered on the curb in front of the apartment building where Varner and his family lived. James and his wife drove past the boys, then suddenly stopped and put the car in reverse, witness Ronald Barnes told police. [3] James’s fateful decision to back his car up to the crowd of boys would lead to a series of events that left a young man dead on the street, produced a high-profile criminal trial with a surprising outcome, and led the Supreme Court of Georgia to trump the trial verdict with an unexpected decision of its own.

The Atlanta Constitution reported on the arrest of William and Edna James, The Atlanta Constitution, September 14, 1966.

Earlier that evening, according to a statement of the facts for the case that reached the Supreme Court of Georgia, James and his wife had had a confrontation with a separate group of black teenagers. Someone had called “Hey baby,” or “Hey, sweetheart,” to Mrs. James while she and her husband were driving.[4] Incensed, Mrs. James pulled a gun out of a paper sack, but the group dashed from the car and ran away. Several minutes later, the couple drove past a group of people standing outside Varner’s home at 420 Boulevard, two miles from the gold dome of the Georgia state Capitol. James suspected that someone in the group had called out to his wife, and he stopped the car, the high court’s statement of the facts show.[5] Witness Ronald Barnes told police that James backed up the Chevy to the apartment building and yelled out to the crowd, “You talking to us?” Alex King, one of the teenagers in the group, replied that no one had said anything, but James pushed his wife back and fired his pistol six times through the open car window, King told authorities. One of the bullets struck Roy Wright, Varner’s sixteen year-old friend, wounding him in the back and side, and another bullet hit Varner in the left eye.[6] James and his wife raced from the scene, speeding south on Boulevard, witnesses told police. Shortly after, Atlanta police sergeant Marvin J. Spears arrived on the scene and was shot in the head. Ambulances rushed to take Sgt. Spears to Grady Hospital, while the two boys were taken after Spears in a second ambulance, a delay that many black observers criticized.[7]

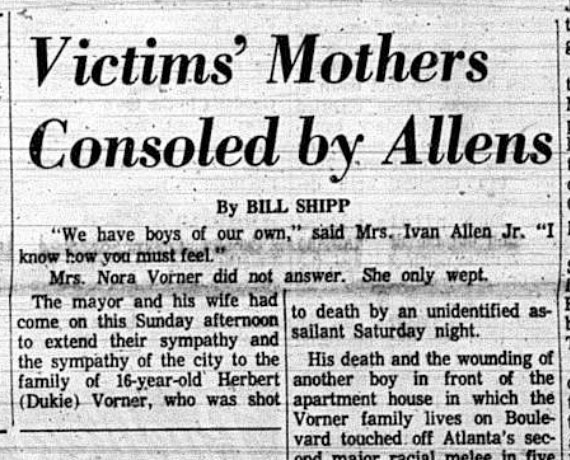

The Atlanta Constitution ran this article about the attention paid to Hulet Varner Jr.’s mother, Nora Varner, by Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen and his wife, The Atlanta Constitution, September 7, 1966.

The shooting death of Varner incited another round of racial violence that evening, the second in five days. Mayor Allen and his wife visited the mothers of Varner and Wright the following day to offer their sympathies. “We have boys of our own. I know how you must feel,” Mrs. Allen told an inconsolable Nora Varner.[8] Mayor Allen offered a $10,000 reward for the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators of the shooting and pledged “the full forces of the city government…to apprehend and convict the person or persons guilty.”[9]

Two days later, William Haywood James and his wife, Edna Ruth James, were arrested and arraigned for the fatal shooting. James, who had a seven-page police record dating back to 1942, and was already on bond from a September arrest for robbery, pleaded not guilty.[10] A state grand jury indicted James for murder.

In February of 1967, James was tried in Judge Stonewall Dyer’s Fulton County Superior Court. George K. McPherson, the Fulton County assistant solicitor general, prosecuted the case for the state, which sought the death penalty. McPherson had the daunting task of convincing an all-white Fulton County jury to convict a white man for murdering a black man, an improbable assignment considering the near-immunity white juries in the South gave to those who committed racially-motivated crimes against blacks.

On Tuesday, February 7, both sides made arguments before the jury of ten men and two women. In what news accounts consistently referred to as “unsworn testimony,” James told the court that he acted out of fear for the safety of his wife and himself. “I didn’t mean to kill anybody,” James said. “I was protecting my wife.” James claimed that he was “struck on the head with a brick and attacked as he and his wife drove through the Boulevard section of Atlanta,” according to The Atlanta Constitution reporter Reuben Smith.[11] James added that he shot “a couple of times” in self-defense.[12] The defense, in an attempt to strengthen its argument that James only fired after blacks attacked him, contended that the riots were in progress before Varner was killed.

Detective Lieutenant J.E. Helms, however, testified that there were no disturbances in the area before the shooting. The state called four eyewitnesses to the shooting, all of whom testified that James had shot Varner unprovoked. McPherson, the Fulton County assistant solicitor general, argued to the jury that James fabricated his story. Then, in a very unusual and blunt pitch to jury members, the assistant solicitor general challenged them to find James, a white man, guilty of murdering a black youth, a crime that often went unpunished in the Jim Crow South. “You have an opportunity to destroy an ugly, malicious stigma––that a white man will not be convicted in the South of murdering a Negro,” McPherson told jurors. “I ask you to find this man guilty of murder regardless of how you feel toward the Negro population. Are we going to be another Alabama or Mississippi?”[13]

The following day, the jury found James guilty of murder. The prosecution asked for the death penalty, but the jury recommended mercy. Upon the jury’s binding recommendation, Judge Dyer sentenced James to life imprisonment.[14] McPherson’s plea to break the South’s well-documented history of acquitting whites for racially-driven murders had resonated with the jurors.

James’s attorneys Charles Muskett and Charles Moore filed an appeal of the verdict to the Supreme Court of Georgia. James’s attorneys claimed the trial judge made twenty errors that should lead the state Supreme Court to reverse the jury’s verdict. On October 9, 1967, a unanimous Georgia Supreme Court handed down its verdict. The court rejected seventeen of those claims. Nothing the court said about the other three suggested it had found the errors fatally harmful to James’s defense.

Led by Chief Justice W.H. Duckworth, the unanimous high court found that Judge Dyer erred in denying the admission of the testimony of two witnesses, Fred Riley and Officer Marvin J. Spears, who was shot the night Varner was killed. James’s attorneys had argued that the officers would have been able to support James’s account that he acted in self-defense in “riotous conditions.” The Supreme Court agreed with James’s attorneys. The high court said that the possible testimony from Riley and Spears was relevant “to show the conditions existing in that neighborhood and to corroborate the defendant’s statement that riotous conditions existed at the time of the shooting.”[15] Yet both Riley and Spears’ testimonies concerned events that occurred after James shot Varner. Neither witness could have provided evidence to confirm James’s allegation that violence had already erupted before he shot Varner.

The court also ruled that a statement Judge Dyer made about James’s defense counsel in the presence of the jury was “prejudicial” and “improper.”[16]

Eight months after a Fulton County Superior Court found James guilty of murder, the state Supreme Court ruled that Judge Dyer’s exclusion of testimony and his “prejudicial” statement during the proceedings constituted sufficient enough error to overturn the conviction. The court concluded: “Judgment reversed. All the Justices concur.” [17]

At the request of the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Case Project at Emory, a former law clerk to two chief justices of the Supreme Court of Georgia reviewed the high court’s 1967 decision. Virginia Looney, who served as law clerk to chief justices Norman Fletcher for 12 years and Carol Hunstein for three years, and served as the City of Atlanta’s ethics chief for eight years, said she was surprised the jury verdict was overturned. “I found the opinion annoying because it did not distinguish between error, harmless error, and reversible error,” she wrote in her analysis.

Looney also asserted that the “trial court was correct [in denying admission of testimony on events that took place after the homicide to show riotous conditions existed at the time of the shooting].” “Of what relevance are events after the defendant killed Varner?” Looney concluded.[18]

On January 22, 1968, more than three months after the Georgia Supreme Court overturned James’s life sentence, James entered a plea of guilty to voluntary manslaughter for Varner’s murder. The historical records that have been gathered on this civil rights cold case are unclear about what led to this outcome. Judge Mack G. Hicks sentenced James to twenty-years in prison to run concurrently with a six-year sentence James was already serving for an assault-with-intent-to-murder charge. On January 29, James’s sentence was amended to serve fourteen-years in prison with six years of probation following the time served.[19]

Not long after James was paroled, he was arrested again, this time for the July 1973 armed robbery of a liquor store. He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Again he appealed to the Supreme Court of Georgia. This time, the high court upheld his conviction.[20]

Edited by Hank Klibanoff

“Parolee Goes Back For Life,” Associated Press, Florence (S.C.) Morning News, Sept. 29, 1973, accessed through newspaperarchive.com.