| By Isabel Hughes, Ross Merlin and Nitin Aradhya |

On Sunday, December 22, 1957, residents of the bustling West Georgia city of Columbus were busy with holiday preparations. But not Clarence Pickett.

“Baby, I am dying,” he told his friend Bessie Smith. “I feel like every breath will be the last.” [1]

Just a few hours earlier, Pickett, who was around 42-years-old and African-American, had been discharged from the Medical Center in Columbus after being examined by a white physician Dr. John Edgar Harris. A medical intern, Harris, 24, was a recent graduate of the Tulane School of Medicine. [2] Whatever he had done during his examination had brought no relief to Pickett, who was suffering from stomach pain so severe that he could barely walk or stand. [3] It then fell to Smith to help her friend. She went to a local pharmacy and bought Milk of Magnesia (an over-the-counter antacid medication), as well as rubbing alcohol and liniment, which she rubbed on Pickett’s stomach. [4] Smith, who had no professional medical training, couldn’t have known that she was attempting to fight the onset of peritonitis, an infection of the tissue lining the digestive system. Left untreated, the infection could be fatal.

In contrast to Smith, John Edgar Harris was a trained doctor of medicine. Given the medical knowledge about peritonitis at the time, as well as x-rays presented to Harris during his examination of Pickett, the doctor should have recognized that his patient was in mortal danger and admitted him to the hospital for treatment. Instead, an internal Columbus police report uncovered by the FBI in 1958 indicates, Harris told a police officer, Harris told a police officer, “I definitely think he is putting on.”[5] He then ordered that Pickett be given 75 mg of the painkiller Demerol, wrote him a prescription for Empirin, a form of aspirin,[6] and discharged him from the hospital.

The next day, Clarence Pickett was dead.

The medical cause of his death is explained in an autopsy conducted on December 23, 1957. However, the larger, more complex reasons why he died emerge when the findings of that autopsy are compared with the findings in the medical report filed by Harris on Deember 22, shortly after his examination of Pickett. Taken together, these two reports raise several key questions: Why did Harris fail to properly treat Pickett? And what, if anything, does that failure reveal about the quality of medical treatment received by African-Americans in the South during the Jim Crow era?

Harris’s examination of Pickett had its roots in events that occurred a day earlier, events that reflected the intense racial hostility often faced by African Americans living in the segregated South. Pickett, a preacher and ad salesman for a black-owned newspaper, had been arrested on a charge of public drunkenness. Pickett had faced similar charges on earlier occasions.[7] He’d also spent six months at the state mental hospital in Milledgeville in early 1957 for what his sister later described as “insanity” [8] By December of that year, Pickett, who was tall and lean and sported a mustache, was a recognized figure to the white police officers of Columbus. In fact, the day before Pickett’s death, Officer J. D. Quattlebaum, had encountered Pickett, his friend Bessie Smith, and his sister Lillie Banks on the street and inquired: “Reverend, is you – yes, you are drunk again.”[9] Quattlebaum was inclined to arrest Pickett, but he relented after some pleading from Smith. He allowed Pickett to leave with Smith and Banks.[10]

Later that same day, police did arrest Pickett near his sister’s home following a complaint that he had cursed and made “smart remarks” to the white female manager of a grocery store. [11] Behind bars at the city jail, Pickett became restive and started to rant loudly. Enter Columbus Police Officer Joseph Eugene Cameron. Determined to stop Pickett’s outbursts, he went to the preacher’s cell and beat, kicked, and stomped him, according to other prisoners at the jail. [12] Cameron later acknowledged his conduct, but said he’d acted only after Pickett had grabbed the officer’s legs.[13]

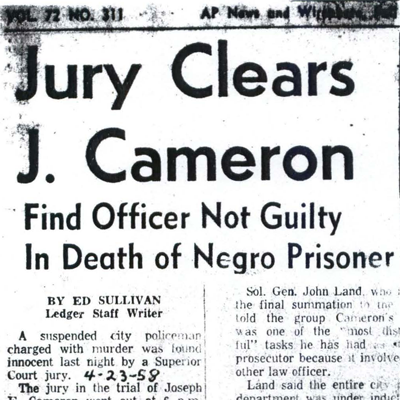

Upon his release from jail, Pickett was unable to walk upright and had to be helped to his sister’s car. Pickett’s sister Lillie Banks was shocked to see her brother’s condition. Pickett told Banks that a policeman had stomped and beaten him.[14] Banks then called an ambulance, which transported Pickett to the Columbus Medical Center where Dr. Harris treated and released him.[15] Within 24 hours Pickett was rushed back to the hospital. This time, he was dead on arrival. Pickett’s death made national headlines, prompted an FBI investigation, and resulted in murder charges against Cameron (a trial jury found him not guilty). However, none of those events resolved the questions about what role race might have played in the poor medical treatment Pickett received before his death. An autopsy revealed that Pickett had died of “shock and toxemia due to peritonitis, resulting from traumatic rupture of duodenum.”[16] However, some experts argue that death’s like Pickett’s reflected a centuries-old pattern of medical racism.

Beginning in the 19th century, race-based ideologies began creeping into modern science[17] and tangibly influencing the study and practice of medicine. [18]Racist ideas, rather than objective knowledge often biased the content and results of scientific studies, which ultimately influenced medical teachings and findings. Among the more pernicious tenets of this quasi-scientific teaching was the doctrine of black “hardiness” which held that the nerves of black people were thicker and less sensitive than those of whites,[19] giving blacks higher pain thresholds.[20] This damaging assumption led many doctors to disregard or under-diagnose expressions of pain by black patients,[21] according to writer and linguist John Hoberman, who has studied medical racism. Hoberman once observed that the hardiness doctrine was so prevalent that it even led many blacks to disregard their own symptoms[22] and decline to seek the medical treatment they needed.

Harris’s notes suggest that he saw little relationship between Pickett’s pain and his injuries. For example, one of Harris’ reasons for not providing a comprehensive initial diagnosis of Pickett was “the apprehension and anxiety shown by the patient during examination not related to the trauma.”[23] In other words, Pickett’s anxiety was not a result of his pain, according to Harris.

There was ample evidence that Pickett’s pain was real. He’d spent much of the day clutching his stomach[24] and had told almost anyone who would listen, including Harris, about the jailhouse beating. [25] Oddly, Harris reported finding no evidence of serious injury but later contradicted himself, noting that Pickett had multiple contusions in the abdomen and pelvic area. [26]

Dr. Mark Allen Edgar, a pathologist at Emory University Hospital wondered if Harris’s early and highly subjective conclusion that Pickett showed no external evidence of violence revealed “a bias on the part of the examiner,” a bias that favored the white police officer who had brutalized his black patient. Dr. Edgar also questioned Harris’s failure to identify Pickett’s abdominal tenderness as a symptom of peritonitis and wondered why, if Harris thought Pickett was faking, he gave him Demerol, a strong narcotic pain-reliever.

“He [Pickett] must have been showing them good signs that he was in significant pain,” said Dr. Edgar.

The Emory pathologist also questioned Harris’ use of Demerol in a patient with acute stomach pain because the powerful analgesic can cause the bowel to “just sort of stop working.”

Harris had other evidence that Pickett was in intense pain and medical distress. His own notes state that Pickett had “rebound tenderness”[27] a possible symptom of acute peritonitis. Then, there were the x-rays. Dr. John H. Deaton, a radiologist at the Medical Center, examined x-rays of Pickett and found “a somewhat bizziare [sic] mottled lucent pattern noted in right side of abdomen.” Deaton speculated that the pattern was feces accumulating in Pickett’s colon,[28] raising the possibility of a painful rupture of the duodenum.

It is impossible to say that Harris could have prevented Pickett from dying, but it is possible to say that if Harris had properly treated Pickett or hospitalized him for closer examination, he would have at least reduced the probability of further damage. Was it possible that Harris didn’t undertake a more aggressive course of treatment because he simply misunderstood his medical responsibility to Pickett? Not likely. In 1956, Dr. Louis Regan, an expert in medical malpractice, articulated a set of responsibilities that all doctors have to their patients. Regan argued that doctors must possess the ordinary skill and learning required of their profession; use care and diligence in applying their skills and learning; and act toward their patients with “utmost good faith.”[29] Those responsibilities, which presaged the Patient’s Bill of Rights adopted by the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons in 1995, are now recognized and accepted throughout the medical community. Whether or not Harris recognized Pickett’s symptoms as signals of peritonitis, he failed to fulfill his responsibilities. If he did not recognize the symptoms, he did not possess the ordinary learning of a doctor about peritonitis. If Harris did understand the significance of the symptoms, then he did not exercise care and diligence in the application of his knowledge. Harris also demonstrated a lack of what Regan called “good faith” in his patient when he asserted that Pickett was “putting on.” With that assertion, Harris established a clear lack of faith in Pickett and his description of his ailment. And it was that lack of faith that ultimately placed Pickett in peril.

Emory pathologist Edgar observed that when Harris ignored Pickett’s explanation for his suffering (the jailhouse beating), [30] he may have been trying to downplay the severity of Pickett’s condition. And once that occurred, it was unlikely that Pickett would have received care appropriate to his condition.

It’s possible that Harris knew that Pickett had peritonitis but failed to understand the mortal danger it represented. However, if that’s true, Harris failed to grasp the magnitude of a condition that was all-to-obvious to Dr. Joe M. Webber, the physician who performed the autopsy on Pickett the next day. Webber reported finding a hole in Pickett’s duodenum (the upper part of the small intestine) and discovered “[a] severe hemorrhage within the mesentery of the great bowel.”[31] Webber also found “severe peritonitis of all the serosal surfaces of all the intestinal tract,”[32] which ultimately led to Pickett’s death. Ironically, Harris’ own notes both foreshadow Webber’s findings and contradict his own statement about Pickett “putting on.” Pickett, the notes said, had abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, and voluntary muscle guarding.[33] All of these, according to Emory’s Edgar, are indicators of peritonitis.

With so much evidence right under his nose, Harris must certainly have recognized the signs of Pickett’s peritonitis. In fact, medical literature describing the symptoms of the disorder was rife long before Harris examined Pickett. As early as 1910, Dr. John Deaver had published an authoritative article in the “Boston Surgical and Medical Journal” (a precursor of the “New England Journal of Medicine”) that listed pain, rigidity, and tenderness as “the cardinal symptoms of acute peritonitis of the upper abdomen.”[34] So even by 1910 standards, Harris had found two of the three “cardinal symptoms” of the disease.

Just eight years prior to Pickett’s death, Dr. W.A. Altemeier gave an indication of the state of contemporary medical knowledge about peritonitis in his article “The Treatment of Acute Peritonitis.” The article, published in 1949 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, cites statistics indicating that both surgery and chemotherapy decreased mortality rates for various forms of peritonitis.[35] Pickett received neither treatment despite the likelihood that Harris, a graduate of a modern medical school, would have been privy to medical knowledge widely accepted for 50 years.

Harris’ own notes seem to reveal a conflict between the reasoned objectivity of modern medicine and a reliance on observations colored by Jim Crow-era misperceptions. Harris noted that following the examination, Pickett became very relaxed and went to sleep on the examination table without sedation.[36] However, given the pain associated with peritonitis, it’s unlikely that Harris would have dozed off, said Dr. William Pendergrast. A 95-year-old former surgeon who practiced in the 1950s, Pendergrast said it is highly unlikely that a patient with a ruptured duodenum — as Webber’s autopsy of Pickett showed — would have been able to sleep.[37] Did Harris’s report of the sleeping patient owe more to racist fancy than to scientific fact? According to writer Hoberman, many white doctors of Harris’ time subscribed to the belief that African Americans were more capable of and apt to sleep. This so-called “sleepy Negro syndrome” even turned up in early medical texts, according to Hoberman. It is possible that Harris’ note about Pickett’s sleeping reflected a belief in this “syndrome.”

The reason why Harris failed to properly treat Pickett might well have been rooted in his inexperience or even simple incompetence, but his notes clearly indicate that he had the ability to identify the symptoms of peritonitis. Harris also knew enough to order x-rays, but apparently concluded that they showed nothing that warranted further examination, even the “somewhat biziarre mottled lucent pattern” reported by radiologist Deaton.

It is probable then that Harris’ lethal decision to discharge Pickett wasn’t driven by inexperience or medical ignorance.

Had Pickett been a white man, his story might have turned out differently. However, as writer Hoberman observed, the tragic dynamics of Jim Crow medicine dictated that “people who were worth less than whites simply did not warrant proper medical attention.”[38] Of course, the record does not indicate whether Harris had his own set of racially biased convictions that influenced his practice of medicine.[39] But as a doctor in the South in 1957, he certainly would not have been an anomaly if he had. In any case, this much is certain: Clarence Horatious Pickett was not “putting on.”

Edited by William R. Macklin and Hank Klibanoff

[1] SAC Maurice Foshee, Atlanta, to Director, FBI, 1/17/58, JOSEPH EUGENE CAMERON, CLARENCE HORATIUS PICKETT-VICTIM. Bureau File 44-12692-10. Transcript of Coroner’s Hearing, January 8, 1958.

[2] Obituary of Dr. John E. Harris, Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, Dec. 12, 2014

[3] Testimony of Lillie Banks, Coroner’s Hearing Report

[4] Testimony of Bessie Smith, Coroner’s Hearing, January 8, 1958, 23-24

[5] Statement of Columbus city patrolman A.L. McCrone to Columbus Police Department, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, December 30, 1957.

[6] Medical Examination from Dr. John Edgar Harris, The Columbus Medical Center, December 22, 1957

[7] Testimony of Lillie Banks, Coroner’s Hearing Report, 21.

[8] Testimony of Lillie Banks, Coroner’s Hearing Report, 21

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Statement of (arresting officer) Bartow J. Robinson to Columbus Police Department, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, December 23, 1957

[12] Interview Report with Ralph Dudley, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, January 3, 1958.

[13] Interview Report with Capt. Clyde Adair, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, January 3, 1958.

[14] Prisoners at the jail also confirmed that Pickett had been severely beaten by a white police officer

[15] Statement of Willena Burke, Interview with Willena Burke on January 2nd, 1958

[16] Foshee Report: Autopsy Report by Dr. Joe M. Webber.

[17] Science became professionalized and institutionalized in the 19th century and many consider this the beginning of the modern scientific age

[18] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 100

[19] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 92

[20] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 100

[21] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 100

[22] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 127

[23] Foshee Report: “Medical Consultation” by Dr. John E. Harris

[24] Interview Report With Henry A. Batts, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, January 2, 1958

[25] Statement of A.L. McCrone to Columbus Police Department, FBI Files on Clarence Horatious Pickett, December 30, 1957.

[26] Medical Examination Report by Dr. John Edgar Harris, Coroner’s Hearing Report, December 22, 1957

[27] U.S. Department of Justice, “Clarence H. Pickett FBI Report, compiled by SA Maurice L. Foshee”

[28] FBI File – C Pickett MD’s Testimony to Coroner’s Jury

[29] Louis Regan, Doctor and Patient and the Law (St. Louis, MO: The C.V. Mosby Company, 1956), 41.

[30] Dr. Mark Allen Edgar, interview by Brett Gadsden, Hank Klibanoff, & Emory Undergraduates, October 1, 2014.

[31] Autopsy Report of Clarence H. Pickett, The Medical Center, Coroner’s hearing, January 8th, 1958

[32] Autopsy Report of Clarence H. Pickett, The Medical Center, Coroner’s hearing, January 8th, 1958

[33] Dr. Mark Allen Edgar, interview by Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class, October 1, 2014.

[34] Dr. John B. Deaver, “The Diagnosis and Treatment of Peritonitis of the Upper Abdomen,” Boston Surgical and Medical Journal 162.15 (1910): 486.

[35] Dr. W.A. Altemeier, “The Treatment of Acute Peritonitis”, The Journal of the American Medical Association, 139.6, 1949: 347-352

[36] U.S. Department of Justice, “Clarence H. Pickett FBI Report, Transcript of Coroners hearing,” 20.

[37] Pendergrast, William, Interviewed by Isabelle Hughes, iPhone recording, Atlanta, GA, October 24, 2014

[38] Hoberman, John. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism, 100

[39] In early January, 2015, the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project tried to contact Dr. Harris by phone in Mississippi, where he practiced medicine from 1961 until he retired in 2011. His wife said he had died three weeks earlier, in December 2014, at age 81.