| By Jordan Friedman |

Irene Gladden sat quietly in her jail cell at Terrell County Jail during the evening of April 20, 1958. Her roommate, Mary Carolyn Clyde, was staring out the jail cell window. Suddenly, Clyde saw something that caught her attention.

“Come here,” she said to Gladden. “They bringing a man in.” Gladden joined her at the window and, to her surprise, saw a familiar face. A man in handcuffs was being led through the jailhouse entrance.

“Who is that?” Clyde said to Gladden, according to an account Clyde would later give in a deposition.

“Some Brazier boy,” Gladden replied.

“I don’t know him,” Clyde said.

“Well, I do,” Gladden responded.[1]

Gladden was referring to James Brazier, who had been arrested and charged earlier that day for interfering with Dawson Police Officer Randolph McDonald’s arrest of Brazier’s father, Odell Brazier, for driving recklessly. McDonald would claim Odell Brazier, who was driving from church, was drunk.[2]

After James Brazier’s death — which his wife, Hattie Brazier, later claimed in a lawsuit was a murder carried out by police officers at the jail — Gladden provided the Brazier’s attorney, Donald Hollowell, firsthand information that indicated she would be a crucial eyewitness in his case had she not died in 1962, three months before depositions began and six months before the trial started. During the trial, civil rights attorney Donald Hollowell said Gladden died under “peculiar circumstances.”[3]

Gladden’s perspective offers a firsthand account from an inmate who was present in the jail the night police officers physically beat and perhaps murdered Brazier. Despite her death, FBI and court documents reveal her importance in the case. Her death also raises questions about the issue of witness intimidation in the case.

Gladden was 35 years old at the time of Brazier’s death and 40 when she died, according to death records.[4] In April 1958, she was serving an 18-month sentence for selling untaxed whiskey, court and FBI documents show.[5] [6] Other FBI documents, including a list of inmates and an interview with the jail cook, Nettie Cate, confirm Gladden’s presence in the jail the night of Brazier’s beating.[7] [8]

Indeed, at the time of Brazier’s death, FBI investigations into the murders of blacks were becoming increasingly common, as they had grown significantly in number starting in the 1940s.[9] The fact that the FBI gathered information on Gladden through interviews and other documents, therefore, is not all too surprising.

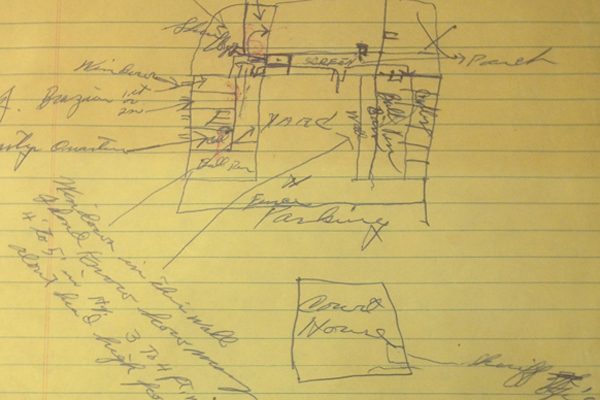

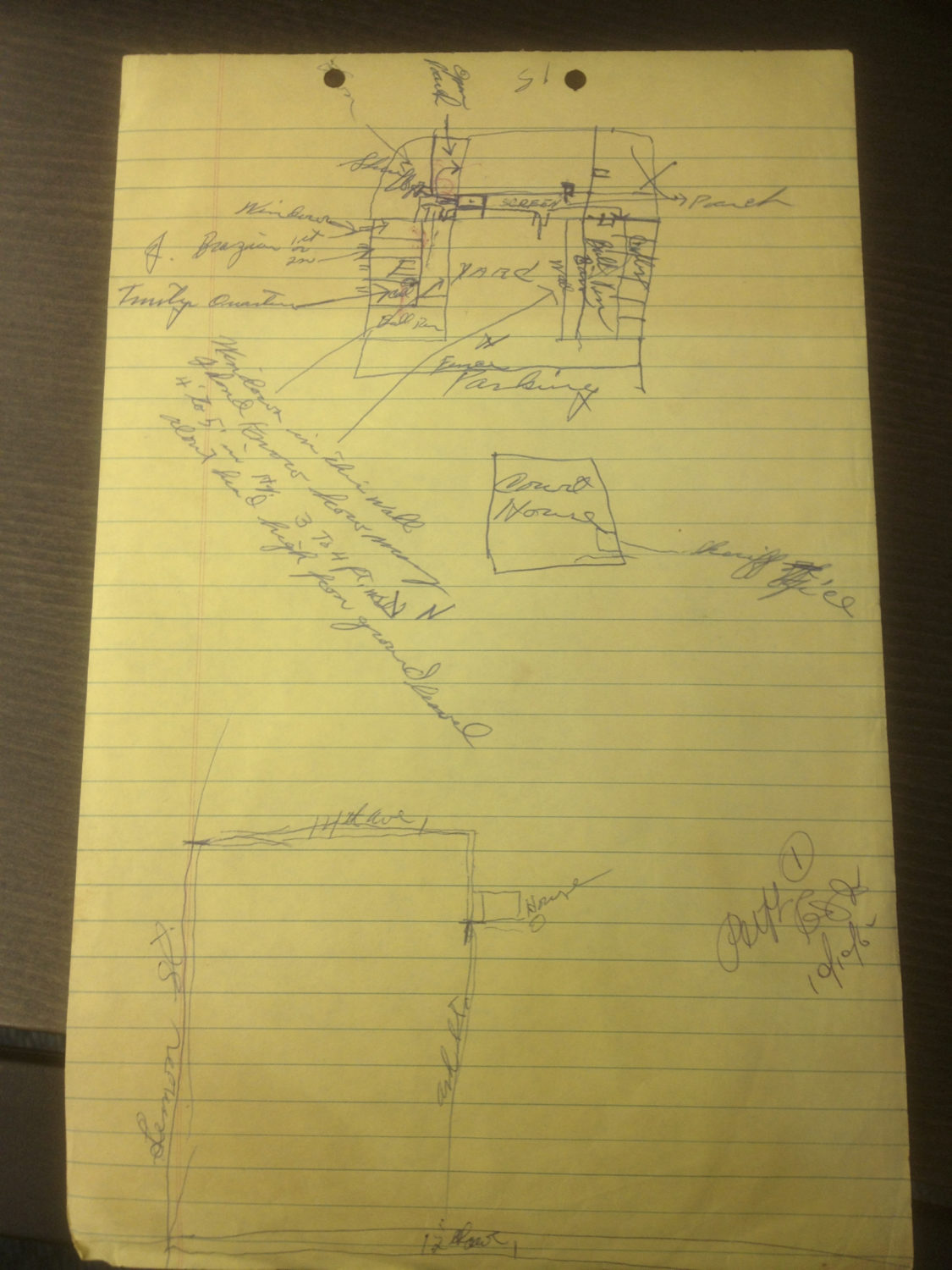

Upon his arrival at Terrell County jail, Brazier was placed in the men’s wing in a cell with Marvin Goshay, who had been arrested for disorderly conduct, Goshay would later tell Hollowell in a pre-trial interview.[10] A map Hollowell drew by hand shows the women’s wing on the left side, and the men’s on the right, with the two wings separated by a screened-in porch.[11]

Soon after Brazier’s arrival — a precise time is not known — McDonald woke up Eugene “Gene” Magwood, a black prison trusty who slept in the women’s wing, telling him to “go and get James,” Gladden would later tell Hollowell.[12] Gladden lay awake in her cell and recognized something unusual taking place: Magwood was bringing Brazier over to the women’s wing, placing him in a cell next to her and Clyde.[13]

With the lights on in Gladden and Clyde’s cell, Gladden could see through the cell door window that Dawson Police officers W.B. Cherry and Randolph McDonald were removing an inmate from the cell next door, though she couldn’t see Brazier himself. Still, she could hear them exiting the cell and walking away. Then there was silence.[14]

After a little while, the officers returned, escorting Brazier. Gladden could hear the officers put Brazier back in the cell next to hers.

“They done put him in this cell right here by us,” Gladden said to Clyde, according to Clyde’s testimony. Gladden knocked on the wall. Nobody answered.[15]

In the broad daylight of the next morning, Gladden looked out of her jail cell door. She saw Brazier with his head “slightly bowed,” she later said.[16] Two “white men” were helping Brazier move about, at one point picking him up off the floor.[17]

Brazier was covered in blood. His shirt was torn. He wore no shoes, his feet exposed as he dragged his right leg “like it was broken, and he was limpin’ on the other,” Gladden said.[18]

Indeed, in the Jim Crow South, police brutality against blacks was common as a way to illustrate white superiority during that time. “In many, but not all, Southern communities, Negroes complain indignantly about police brutality,” economist Gunnar Myrdal wrote in An American Dilemma. “It is part of the policeman’s philosophy that Negro criminals or suspects, or any Negro who shows signs of insubordination, should be punished bodily, and that this is a device for preventing crime and for keeping the ‘Negro in his place’ generally.”[19]

Once Brazier was taken from the Terrell County Jail to mayor’s court to face charges of resisting arrest, Clyde and Gladden entered his cell during the “runaround,” as Gladden called it in her interview with Hollowell, referring to the period when inmates can leave their cells and are free to roam around.[20] That’s when they spotted Brazier’s blue blanket and the mattress where he had slept. Both items were covered in blood.[21]

In a deposition she gave prior to the trial of Hattie Brazier’s lawsuit against the police officers and the sheriff, Clyde told a story similar to the account that Gladden discussed with Hollowell. At first, she said she and Gladden were together when they entered the jail cell but later, during the trial of Hattie Brazier case, Clyde denied that very statement.[22] Years later, in an in-person interview, however, she acknowledged that she felt intimidated by the presence of the police officers in the courtroom, and felt she had to “say what they told me to say.”[23]

In the Jim Crow South, a black person did not know when a white man or woman might use physical force against him or her. “Violence may occur at any time,” Myrdal wrote, “and it is the fear of it as much as violence itself which creates the injustice and the insecurity.”[24]

Irene Gladden’s story ends rather abruptly. She died in August 1962, according to Georgia death records,[25] six months before Hattie Brazier’s lawsuit against Dawson police officers Cherry and McDonald, as well as Terrell County Sheriff Z.T. (Zeke) Mathews, went to trial. The cause of death is unknown at this time. During Clyde’s deposition, Hollowell refers to the death of Gladden — as well as that of Marvin Goshay — as “peculiar,”[26] and he is likely inferring that the police officers might have had something to do with the deaths to prevent key witnesses from revealing the truth.

“Whites could cheat and steal from Negroes, knowing that when it was white testimony against Negro, white almost always prevailed,” Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff wrote in The Race Beat.[27] Could it have been that Gladden’s testimony might have been so strong that it could have contributed to a guilty verdict? Did the officers therefore have something to fear? While this has not been confirmed, in the Jim Crow South, it was all too possible.

Edited by Hank Klibanoff

The dialogue is not confirmed but is merely what Clyde recounts during her deposition. She later denied much of the information she states in her deposition, then even later said he did not feel she could tell the truth when she saw the accused police officers, including officers Weyman Cherry and Randolph McDonald, in front of her in the courtroom. Clyde also clarifies in an FBI report that Officer Weyman Cherry was holding onto Brazier’s arm so he could not run away. When was this?

Earlier that day, McDonald had pulled Odell Brazier over for allegedly drinking and driving. James Brazier tried to stop the officers from beating him. The officers later showed up at James Brazier’s house, hit him with a blackjack and arrested him for interfering with the arrest of his father.

These are the deaths records for an Irene Gladden. They state she died on August 16, 1962 in Terrell County, GA. Described as “colored (black)” and 40 years old.

Hattie Bell Brazier discusses Irene Gladden and tells the FBI she was arrested for selling untaxed whiskey. This differs from Gladden’s Hollowell interview, where she simply says she was arrested for “selling whiskey.”

The spelling of Marvin Goshay’s last name varies from Goshay to Goshea in various records that are part of the James Brazier case.

The time that this was taking place is uncertain. The jail is unlikely to have had a clock visible to inmates, and their sense of the passage of time, not surprisingly, is inconsistent and perhaps unreliable. Goshay said this happened before midnight, while Gladden said it was around midnight when he was taken out. Gladden said Brazier was returned at about 1 a.m. Clyde said he returned about an hour and a half after he left. Dr. Charles Ward, who had examined Brazier soon after he was brought into the jail, said he checked on Brazier again in the middle of the night, around 2:30 or 3 a.m., and noticed nothing unusual. Clyde said she went to bed before 2 a.m., which she said was after Brazier was returned.

Clyde said in her FBI interview that this occurred at around 9 a.m. that day.