| By Erica Sterling |

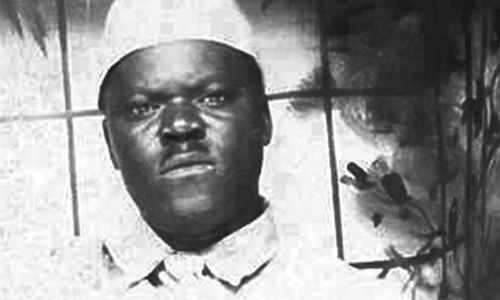

A Man whose Death Inspired the Teenager who Led the Movement

Maceo Snipes must have felt a great sense of pride after he cast his first vote in the contentious 1946 Democratic primary for governor. Like many black World War II veterans, Snipes returned home, to Butler – a town in western Georgia with 1,972 residents[1] – with an honorable discharge and a determination to exercise his rights as a citizen.[2]

For months, Snipes had considered the risks associated with his exercise of the franchise. Even by Jim Crow standards for racially charged elections, this was a particularly fragile time for a black man to seek to vote. The most provocative campaign issue was specifically whether any African-Americans should be allowed to vote in the Democratic primary. Georgia had long allowed only whites to vote in the Democratic primaries; advocates of the whites-only primary said blacks could vote instead in the general election. But since Georgia was essentially a one-party state where winning the primary assured victory in a pro forma general election, the black vote had no influence.

In a decision the Georgia political establishment vowed to defy, federal courts earlier in 1946 had struck down the whites-only primary.[3] So Snipes was seeking to vote in the first election held without the statewide ban on black voting. That campaign pitted one of the most racially polarizing figures in Georgia history, two-term former Gov. Eugene Talmadge, who pledged to reinstate the all-white primary, against a somewhat more progressive James V. Carmichael.

Despite threats from the Ku Klux Klan in the run-up to the July 17 primary, Maceo Snipes took the bold step to become the first African American to cast a vote in Taylor County.[4] What happened over the next several days in Butler and two hours away in Monroe, Georgia, would grab headlines across the nation, especially in the African-American press, and prompt a young Morehouse College student, Martin Luther King Jr., to write a letter of response to the editor of The Atlanta Constitution.[5]

The day after Snipes voted, four white men arrived in a pick-up truck outside of his grandfather’s farmhouse, where Snipes and his mother Lula were having dinner. The men, rumored to be members of the local Klan chapter, called for Snipes, who came outside to meet them. During their encounter outside the house, Edward Williamson, who sometimes went by the name of Edward Cooper, shot Snipes in the back. Williamson, like Snipes, was a World War II veteran.[6]

As recounted by his descendants, Snipes was wounded and struggling but still ambulatory as he and his mother walked about three miles to the home of Homer Chapman for help. Chapman owned the land where Snipes and his mother worked as sharecroppers. By one account published at the time, Chapman “helped take the wounded Negro to the hospital.”[7] Snipes’ descendants today say Snipes and his mother went to the home of Snipes’ sister Katie, whose two sons, Sam and Eddie D.,[8] drove their uncle to Montgomery Hospital in Butler.[9] Snipes waited in a hospital room that better resembled a closet, as the doctor on duty attended to other patients.

Approximately six hours lapsed from the time Williamson shot Snipes until the doctor performed surgery to remove the bullets, the family would later say. The story that still resonates from that day in the Snipes family carries the same theme of medical neglect found in other Georgia civil rights cold cases: Not long before he died, Snipes was talking actively with his family. The white doctor at one point said Snipes would need a transfusion, then said it would be impossible because there was no “black blood” available at the hospital.[10] Mirroring every other facet of life in the Jim Crow South, the enforced separation between blacks and whites extended to blood transfusions.[11] Without a transfusion, Snipes died from his injuries two days later, on July 20.

Five days later, in Monroe, Walton County, two black couples — Roger and Dorothy Malcom and George and Mae Murray Dorsey — were abducted and taken by a mob of 15 to 20 white men to the Moore’s Ford Bridge above the Apalachee River near the Walton and Oconee county lines. Tied to trees, they were being beaten and shot to death. Mae Murray Dorsey was seven months pregnant.

Rumors subsequently spread throughout the community that anyone attending Snipes’ funeral would meet the dead man’s fate.[12] And so — in the dead of night — the funeral director of McDougald Funeral Home in Butler, joined by Snipes’ uncle Felix, buried the deceased in an unmarked grave in Butler Cemetery.[13] To this day, no one knows the precise location of Snipes’ burial site.[14]

A coroner’s court convened on Monday, July 29, 1946, to review the cause of Snipes’ death. Williamson told the coroner’s jury that Snipes owed him ten dollars. Williamson, accompanied by a man named Linwood Harvey, a sawmill operator, said he went to Snipes’ home to collect the debt. The exchange between the men turned hostile and escalated. Williamson claimed that Snipes pulled a knife. Pleading self-defense, Williamson testified that he retrieved a gun from the glove compartment of his car, and shot Snipes twice. Coroner J.D. Cooke and the jury found that Williamson’s actions were justified, despite relatives’ testimony that the victim neither owed Williamson any money nor possessed a knife.[15]

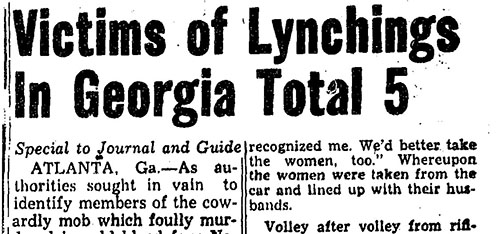

National newspapers covered Snipes death and the murder of two Georgia couples, the Malcoms and the Dorseys, New Journal and Guide, August 3, 1946.

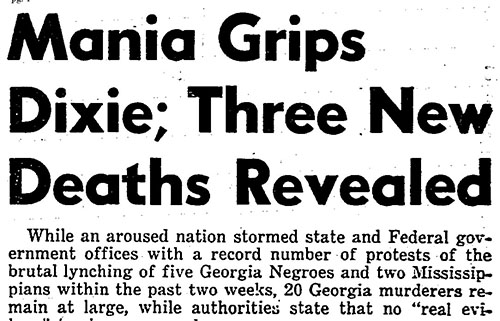

The five racial killings got widespread news coverage, and strong editorial response in the black press. “Victims of Lynchings in Georgia Total 5,” the Norfolk Journal and Guide, an African-American newspaper, reported on Aug. 3.[16] A week later, the Chicago Defender added some Mississippi cases to its story about Georgia and some urgency to its headline: “Mania Grips Dixie; Three New Deaths Revealed.”[17]

“A thunderhead of lynch race-war is burgeoning up on the horizon,” the New York Amsterdam News wrote in an editorial titled “A Call to Arms” on August 3. “The future calls for all hands to ‘put to’ with everything we have.” It closed: BRING THE GEORGIA LYNCHERS TO JUSTICE!”[18] A week later, in an editorial urging New Yorkers to honor Snipes by registering to vote and casting ballots, the New York Amsterdam News called Snipes “a new martyr to the cause of Democracy and freedom in America,” then added, “Maceo Snipes lies cold in his grave because he knew that by means of the ballot is the surest way to destroy the artificial barriers that shut out large segments of America’s population from the full enjoyment of the life which is our heritage.” The editorial closed:”The blood of Maceo Snipes cries out from the redder clay of Taylor (County), Georgia. Register. Vote. Help Build America’s future.”

The story of the deaths were also reported alongside killings in Mississippi, The Chicago Defender, August 10, 1946.

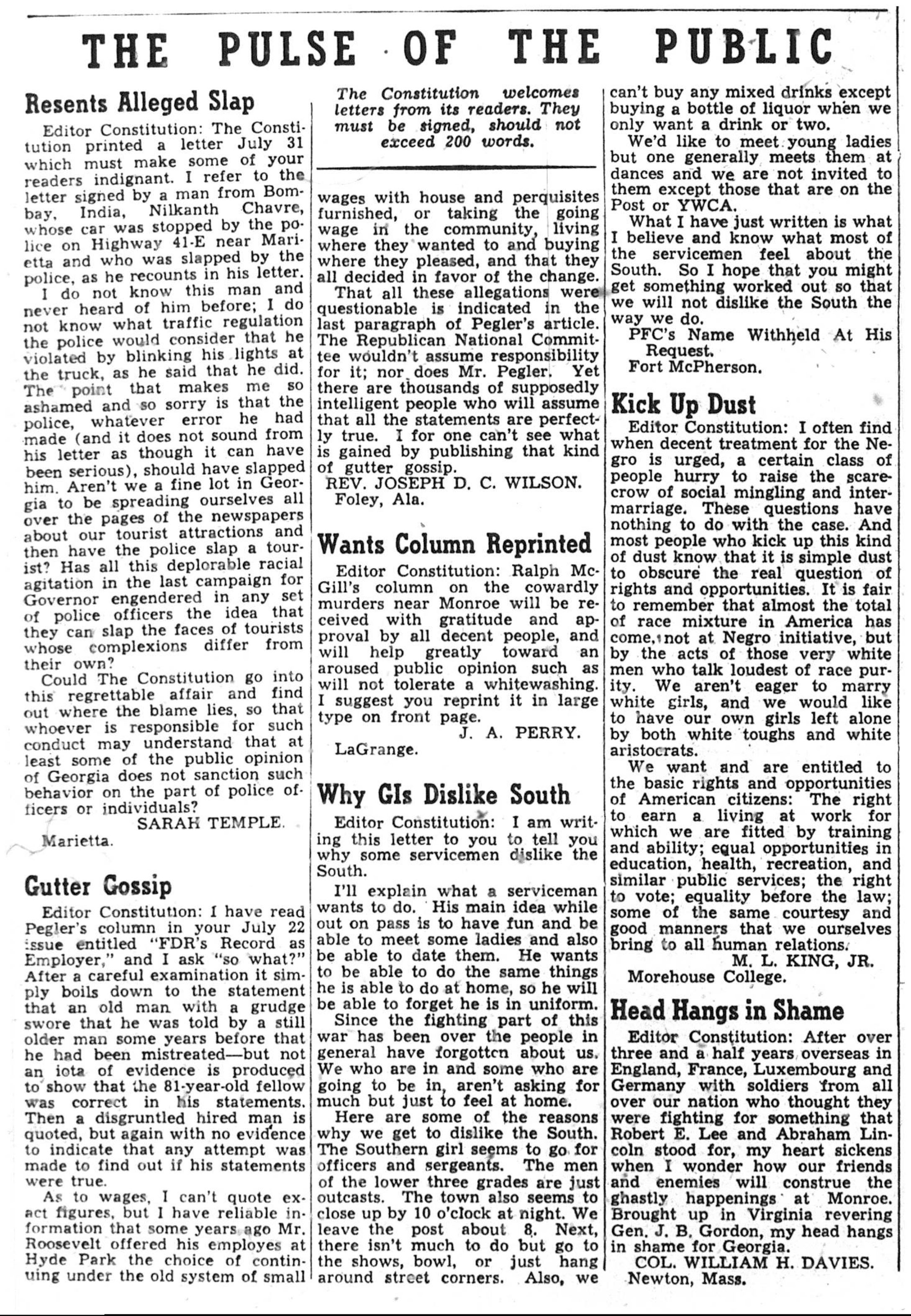

Back in Georgia, a young Morehouse College student, then a teenager, was deeply disturbed by the Snipes and Moore’s Ford killings, and by the overall white response that suggested a misunderstanding among whites about the motives of blacks. In a letter to the editor that Martin Luther King Sr. would later say was the initial “intimation of [his son’s] developing greatness,”[19] Martin Luther King Jr. criticized the white distortion of black interests, that challenged southern white hypocrisy, and provided a sophisticated statement of black goals that would carry him and the civil right movement for the next two decades.

“I often find when decent treatment for the Negro is urged,” the young King wrote, “a certain class of people hurry to raise the scarecrow of social mingling and intermarriage. These questions have nothing to do with the case. And most people who kick up this kind of dust know that it is simple dust to obscure the real question of rights and opportunities. It is fair to remember that almost the total of race mixture in America has come, not at Negro initiative, but by the acts of those very white men who talk loudest of race purity. We aren’t eager to marry white girls, and we would like to have our own girls left alone by both white toughs and white aristocrats.

“We want,” he continued, “and are entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens: The right to earn a living at work for which we are fitted by training and ability; equal opportunities in education, health, recreation, and similar public services; the right to vote; equality before the law; some of the same courtesy and manners that we ourselves bring to all human relations.”[20]

By taking the risk of voting under the threat of death, by his struggle to survive a bullet and medical neglect, and by inspiring the man who would go on to lead perhaps the most significant movement in U.S. history, Maceo Snipes, in the end, prevailed.

Edited and supplemented by Hank Klibanoff

In most 1946 news accounts, Mr. Snipes’s first name was spelled Macio. His family, however, spells his name Maceo.