| By Nathaniel Meyersohn |

A Murder on a Warm Winter Day

The Atlanta Constitution ran this headline on Maybelle Mahone’s murder, The Atlanta Constitution, December 7, 1956.

On the morning of December 5, 1956, B.T. Dukes, a 71-year-old white retired farmer from Molena, Georgia, a small farming town sixty miles south of Atlanta, drove to Maybelle Mahone’s house, two miles outside of Molena.[1] Dukes had worked with Mahone, a 30 year-old black mother of six, at a plantation near Molena and “sometimes went by the Mahone home to talk to them,” according to then-Pike County Sheriff J. Astor Riggins.[2] Dukes spent the unseasonably warm day drinking whiskey with Mahone,[3] whose husband had left for work earlier that morning.[4] By the end of the day, Dukes had shot Mahone dead in front of her young children – he told the sheriff she “sassed” him – triggering a murder trial and conviction in rural Pike County Superior Court, and a retrial with an unexpected outcome. In 2006, fifty years after Maybelle Mahone was killed, then-United States Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales announced a civil rights cold case initiative, with the pledge to re-examine more than 120 unsolved civil rights-era killings that appeared to be racially motivated. The events that led to Mahone’s death placed her on the FBI list of victims.

At around four in the afternoon on December 5, Mahone’s sons, Walter Lee, 11, and Robert Lee, 12, returned home from school.[5] When they walked into the house, they found Dukes and their mother in Walter Lee’s bedroom. Dukes was “laying on the hearth by the fireplace,” and Mahone was “laying on the bed,” Walter Lee would later say. “My mama, she told him to leave and he wouldn’t leave, and he kept laying down on the fireplace…then he went to leave…[but] he [didn’t] leave… She kept on telling him to leave and he still wouldn’t leave, and my Mama told me…to make him leave, and he [still] wouldn’t leave,” Walter Lee recalled.[6]

The situation deteriorated quickly, the young Walter Lee would later tell a Pike County Superior Court jury during Dukes’s trial for murdering Mahone. Finally, Lee testified, Dukes left the house and went to his car. He returned with his single-barrel shotgun (a Winchester Ranger 12-gauge, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation later determined) and put a shell in it, Walter Lee told the court. Mahone headed to the back door of the house. Dukes called to her from the side of his car and said he “wasn’t going nowhere,” Walter Lee testified. Dukes fired his shotgun through the back door, striking Mahone in the neck. [7] Mahone fell, bleeding excessively from her shoulder and neck. Dukes drove away.[8]

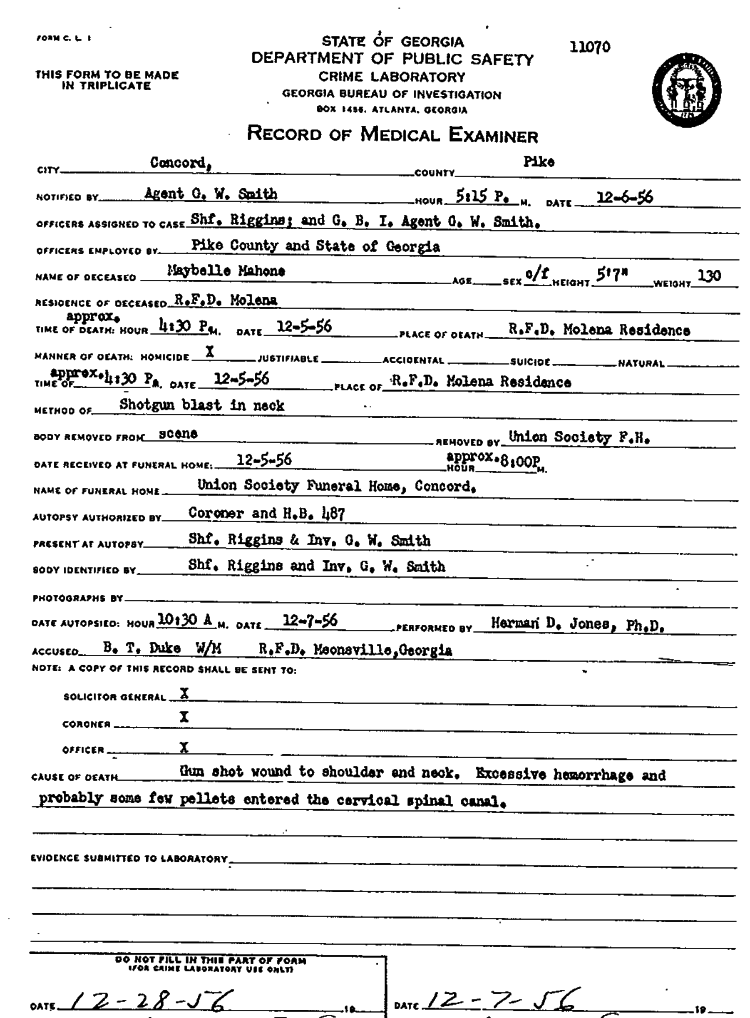

The Georgia Medical Examiner’s report on Maybelle Mahone’s death, from her file with Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

About twenty-five minutes later, Georgia State Trooper Billy Mitchum received a call from the Pike County Sheriff’s office in Zebulon about a shooting at a “colored home west of Molena,” Mitchum later told the Pike County court. Mitchum and another Georgia trooper drove to the home of Mr. and Mrs. J.B. Lawrence in Molena, where they were directed to the Mahone residence. When Mitchum arrived, he “went into the home and [found] the body of a colored female, fully clothed, lying in the rear of the house in the hall. She was lying with the left side of her face down. There was a puddle of blood around the head, and the back door was closed, and her feet were about half a foot or a foot away from the door,” Mitchum told the court.[9]

Walter Lee and Robert Lee told the troopers and Mr. Lawrence that Dukes had been over during the day, so Mitchum and Mr. Lawrence drove to Dukes’s house. Dukes was eating dinner at the kitchen table with his wife when Mitchum arrived. Mitchum placed Dukes under arrest and drove him to the Mahone residence to wait for Coroner Herman D. Jones and Georgia Bureau of Investigation Agent G.W. Smith to arrive.

On the drive to Mahone’s house, Mitchum spoke to Dukes about the shooting. Dukes told Mitchum that the two boys had come home from school around four, “and the deceased ‘sicced’ them on him. [She] made them throw rocks at him and push him down and throw sticks at him…He told [the boys] to quit and they failed to do so. He walked out to his automobile, got out a shotgun, and Maybelle came on the back porch and began to ‘sass’ him. [She] told him wasn’t nobody there scared of him and he fired a shot,” Mitchum testified.[10]

Dukes repeated a similar version of events to Agent Smith during the course of the inquiry by Smith and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. Dukes told Smith that “around three or four o’clock…these two boys of Maybelle’s come in together…and started throwing sticks and rocks at him and pushed him down a couple of times…He told Maybelle to make them quit and she wouldn’t make them quit, and he just went out to his car and got the shotgun and shot her,” Smith would later testify during Dukes’s trial. Smith told the court that Dukes showed no remorse for shooting Mahone, and did not appear to believe he had done anything wrong.[11]

In February of 1957, a grand jury indicted Dukes for murder. Dukes was tried before a Pike County Superior Court jury for murder in the July term. Andrew J. Whalen Jr., the Griffin Judicial Circuit solicitor general, prosecuted the case for the state and sought the death penalty for Dukes. R. Carl Johnson, an attorney from Zebulon, and Dickson Adams, a female attorney from Thomaston, Georgia, represented Dukes, who pleaded not guilty.[12]

Dukes did not testify on his own behalf during the proceedings. None of the testimony provided any explanation for why Dukes was with Mahone – a simple interracial friendship at the time would have been very unusual – but no testimony was sought or given that indicated a sexual relationship, or an attempted one. Throughout the trial, the defense counsel raised questions about Dukes’s mental state. The defense attempted to establish that Dukes was legally insane and therefore not responsible for the murder. Through testimony from Dukes’s children and friends describing his mercurial behavior, the defense sought to establish that Dukes could not distinguish between right and wrong during the time of the shooting and, as a result, should be acquitted. Under Georgia law, suspects were presumed to be sane, so the burden of proof fell to Dukes’s defense counsel to demonstrate––to the reasonable satisfaction of the jury––that its client was mentally ill.[13] The state relied on eyewitness testimony from Mahone’s children, as well as State Trooper Mitchum, G.B.I. Agent Smith, and Sheriff Riggins to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Dukes murdered Mahone.

Dr. Trajan G. Shipley, a psychiatrist who performed a mental examination of Dukes shortly after he was taken into custody, was the defense’s key witness. Dr. Shipley testified that Dukes was “slovenly” and “didn’t seem to care much about what was going on,” when he underwent examination. Dukes, Dr. Shipley said, “showed on the mental examination to be confused. His memory was impaired. His memory for recent…events showed impairment. He had a dream-like attitude about him.” Dr. Shipley told the court that he had diagnosed Dukes with “cerebral arteriosclerosis, a psychosis meaning, in a legal sense, insanity.” Dr. Shipley testified that “[Dukes] was not able to distinguish right from wrong on the 5th of December…[and] was not responsible for his acts.” The doctor also told the court that personality changes were associated with Dukes’s mental condition.

The defense called several witnesses to corroborate Dukes’s pattern of erratic behavior.[14] C.A. Oglesby, a shopkeeper, testified that she’d observed changes in Dukes’s personality over a two-year period; one of Dukes’s daughters, Talmadge Allen, recounted an incident when her father had undressed in the presence of women; his son, Grady Dukes, told the court how he had mentioned the possibility of seeking psychiatric care for his father to his mother; and another of Dukes’s daughters described changes in his personality and his recent detachment from former friends and family members. But the final witness to testify for the prosecution, Sheriff Riggins, told the jury that he had known Dukes for more than thirty years and believed that Dukes was legally sane.

The Atlanta Constitution reported on B.T. Duke’s sentencing for Maybelle Mahone’s death, The Atlanta Constitution, August 1, 1957.

On July 31, 1957, a Pike County jury found Dukes guilty of Mahone’s murder. After deliberating for only two hours, the jury recommended mercy, and Judge John J. McGehee sentenced the 71 year-old farmer to life in prison.[15] Dukes was sent to the State Penitentiary at Reidsville to serve his sentence. The defense sought a new trial in October of 1957, but Judge McGehee dismissed the claim.

On February 17, 1958, the defense filed an extraordinary motion for a new trial, citing new evidence that was discovered after the verdict. In the petition, R. Carl Johnson, Dukes’s attorney, stated that on January 2, 1958, Dukes had been given a mental examination at the Georgia State Sanitarium. Dr. R.M. Bradford and Dr. Edwin W. Allen, psychiatrists at the sanitarium, “found [Dukes] to be psychotic, not mentally able to adhere to the right and refrain from the wrong and not mentally responsible for his actions.”[16]

Judge McGehee held a hearing on the motion and ordered a new trial — for the same day. On February 24, 1958, Judge McGehee convened a Pike County jury and, after a proceeding for which only an outcome and not a full explanation has been discovered in historical records so far, O.C Minter, the jury foreman, read the verdict to the court: “We the jury find the defendant B.T. Dukes not guilty by reason of insanity at the time of the commission of the act alleged.” Judge McGehee ordered Dukes to “be confined at the State Hospital at Milledgeville…or a facility where mental patients are kept,” not to be “released…except with the terms and provisions”[17] set by the Georgia Board of Control, which “[prescribed the]…rules and regulations [for inmates’ admission and discharge to state hospitals].”[18] Dukes died four years later, on June 1, 1962, and was buried at Molena Cemetery in Molena.[19]

In December 2009, three years after reopening the Mahone case and placing it on the list of civil rights cold cases, the FBI closed the case, either because it was satisfied that the ultimate verdict was appropriate, or because Dukes was deceased.

— Edited by Hank Klibanoff