| By Lily Weinberg |

As 21-year-old Marvin Goshay walked through the streets of Dawson on a hot August day in 1958, Police Officer Weyman Cherry abruptly stopped him.[1] Goshay, who had been an eyewitness the night James Brazier was taken from jail and beaten four months earlier, had been subpoenaed to testify before the federal grand jury Macon. The grand jury was investigating whether Cherry and other law enforcement officers were Brazier’s abductors and had delivered his fatal beating. Confused, Goshay asked Cherry why he was being arrested. “You just need to be in jail,” the officer replied.[2]

Although it is unclear what charges, if any, were lodged to justify arresting Goshay, the Dawson Police Department held him in the Terrell County Jail for one week. During this time, the federal grand jury met and refused to indict Cherry and other officers identified by jailhouse witnesses as Brazier’s abductors.

“I never was brought to…court during this time,” Goshay revealed to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission that examined the Brazier case in 1961. “I just stayed in jail. I can only guess, although no one ever told me, that the only reason I was locked up was because they didn’t want me to go to Macon.”[3]

Throughout the civil rights era, white people, especially white local policemen, used their power and authority to sustain a racial hierarchy and create an environment of fear among blacks.[4] Rather than enforcing the law, many policemen felt their main duty was to uphold white supremacy by “[taking] the law into their own hands, assuming the roles of judge, jury, and, sometimes, executioner.”[5]

When black Southerners were finally given the right to testify in court cases, they believed that it gave them a constitutional protection whites had long enjoyed.[6] “But even that precious right,” Leon Litwack wrote in Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, “amounted to little if whites intimidated witnesses and refused to grant black testimony any credibility.”[7] If a black person witnessed a crime, he/she could subsequently fall victim to witness intimidation by police officers. Litwack further explained, “Incidents in which blacks who testified against whites were threatened, murdered, or beaten were commonplace, making many black witnesses to a crime reluctant to become involved in a legal proceeding.”[8] To cover up crimes committed by white people, white policemen routinely coerced black witnesses through beating, arbitrary arrests, verbal intimidation, or eavesdropping. [9]

If Goshay had been free to speak about what he saw, he might have provided critical testimony identifying Brazier’s abductors, information that might have been useful in the federal investigation. The police officers thought to have been involved with Brazier’s death might then have been indicted.[10]

On the night of the beating, Goshay sat in his cell in the Terrell County Jail. [11] At about 6:30 p.m., he would later say, he noticed Cherry and Officer Randolph McDonald bring James Brazier, who was bloody and beat up around his head, into the jail. The handcuffed Brazier, who wore a suit, tie and white shirt, was placed in Goshay’s cell. After some time had passed, Brazier turned to Goshay, struck up a conversation and described his past few hours. Brazier spoke of his father’s interaction with the police officers and his own arrest.[12] Cherry and McDonald “had beat him at his home because [McDonald] hit his daddy and he told [McDonald] not to hit his daddy any more, that he would put him in the car and he [McDonald] could carry him to jail,” Goshay said Brazier explained.[13]

At around 9:30 p.m., McDonald came into the cellblock and directed Brazier to go to the jail office. Brazier, who left without any help, asked the officer where he was taking him. McDonald replied that he was taking him to the office where a doctor could bandage up his head.[14]

A half-hour later, McDonald returned Brazier to the cell and locked him in. Brazier had four bandages on his head, Goshay said. As Brazier sat on his bunk in the jail, he complained that his head hurt, Goshay recalled, and from time to time got up and walked around a little bit.[15]

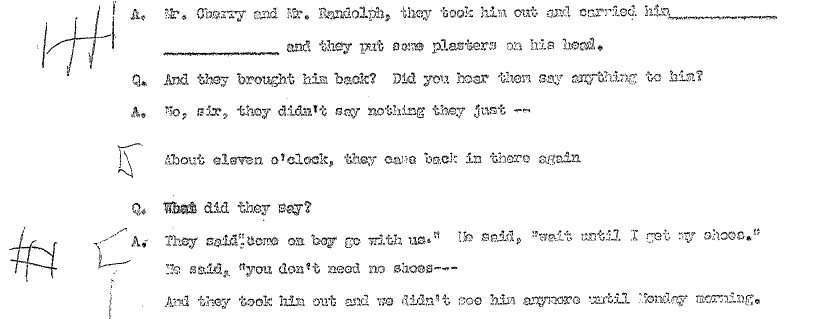

At about 10:30 p.m., Goshay saw Cherry, McDonald and two other men whose faces he could not make out, come back to the cellblock door. [16] The two officers opened the door and walked into the cell where Brazier was locked up. The exchange between the police officers and Brazier went like this, Goshay recalled:

“Come on boy, go with us,” an officer said.

“Wait until I get my shoes,” Brazier responded.

“You don’t need no shoes,” Cherry said with dark portent.

The officers handcuffed Brazier and the three men left the cellblock, with Cherry leading the way and Brazier following without any assistance.[17] “And they took him out,” Goshay told Donald Hollowell, Hattie Bell Brazier’s attorney, in an interview, “and we didn’t see him anymore until Monday morning.”[18]

Marvin Goshay recounts police telling James Brazier he “won’t need no shoes” when they took him from his cell, excerpt from the Donald Hollowell papers, courtesy Auburn Avenue Research Center.

About a half-hour after Brazier and the officers left, around 11 p.m., Eugene Magwood, the prison trusty, came to Goshay’s cell. Magwood told Goshay that Cherry and McDonald had taken Brazier to the hospital. On Monday morning at about 8, Magwood walked through the cellblock area and told Goshay that the officers had brought Brazier back to the jail at about 6 a.m. and “he was getting along fine.”[19]

But Brazier did not look fine to Goshay on Monday morning when Goshay saw Brazier in the hall, which extended from the men’s side of the jail to the women’s side. Brazier looked battered and crippled. Brazier was leaning against a wall and needed help walking, Goshay said. Police Officer Shirah Chapman told Goshay to grab hold of Brazier’s arm. Odell Brazier, James Brazier’s father, had the other arm, and the two men helped him walk out. “His head hung downwards, he didn’t talk. He didn’t appear to hear his daddy when he asked what was the matter with him and where had he been,” Goshay explained.[20] Brazier did not have on the white shirt he wore into the jail and his undershirt was torn in several places.[21] “Look like somebody had beat him and dragged him,” Goshay would later tell Hollowell in an interview. [22] Goshay also noticed that Brazier had blood on his back in addition to welts all across his back, sides and stomach.[23]

Goshay never got to tell his story to the public. He was found dead in a Dawson undertaker’s parlor on March 14, 1961, three years after he shared a cell with Brazier on the night of his beating. The cause of death was “apparently” asphyxiation.[24] The FBI investigation failed to uncover evidence of foul play, although FBI agents thought he died under suspicious circumstances.[25] Goshay would have had another opportunity to testify in court during the trial of Hattie Brazier’s civil suit, which took place in February of 1963, but because of his early death he could not do so. As evident in Hollowell’s interview with Goshay right before his death, it is clear that Goshay would have been an active witness in court and might have helped the Brazier family win justice for James Brazier.

Edited by Hank Klibanoff

Gunnar Myrdal, “The Police and other Public Contacts,” in An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2003), 538.

Interview Report with Marvin Goshay, FBI, June 18, 1958, JAMES BRAZIER, Bureau File 44-13064 (hereafter cited as FBI Files on James Brazier).