| By Ellie Studdard |

Fall, 2015

On September 13, 1948, the Federal Bureau of Investigation headquarters in Washington, D.C., received a copy of a case report from the FBI field office in Atlanta, GA. The report detailed the facts of the assault of Dover V. Carter and the murder of Isaiah Nixon, two black men from Montgomery County, GA. Near the top of the first page of the document are a number of boxes specifying the mundane details of who made the report, when, and where. The last box of the six is simply labeled, “Character of Case.” In this box are five words: “Civil Rights and Domestic Violence.“[i] These five words necessitated the Atlanta field office to file an official case report. They explain why the office would bother the Director of the FBI with the cases of two black men from the middle of rural Georgia. The mere suggestion of a violation of the federal civil rights statutes in the United States Code demanded the FBI’s immediate attention, spurring an investigation in order to bring justice to the men involved in these crimes.

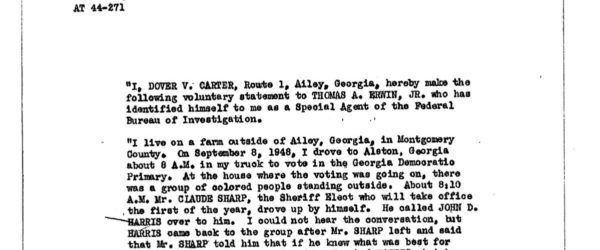

Three days prior, on September 10th, Dover V. Carter gave the statement included in the Atlanta FBI office’s report. In his statement, Carter describes going to the polls to vote in Georgia’s Democratic Primary on September 8, 1948. Carter told the agents that, only hours after voting, he suffered a brutal beating at the hands of Johnnie Johnson and Thomas Wilson, also from Montgomery County.[ii] The beating left Carter bruised and bloody, yet Carter’s injuries paled in comparison to those inflicted on Isaiah Nixon, who also voted in the primary that morning. In the evening of this same primary election day, brothers Johnnie Johnson and Jim A. Johnson paid a visit to Nixon’s home. According to Carter’s statement to the FBI, which was based on a conversation he had had with Nixon after he was shot, Jim A. Johnson asked how Nixon voted and then demanded that Nixon get into his car. Carter said Nixon refused to go. Jim A. Johnson then shot Nixon repeatedly with a pistol.[iii] Nixon was rushed to a hospital. Dover Carter would come to the hospital and speak with Nixon about his story, as Nixon struggled to live. Nixon died from these gunshot wounds two days after he was shot.[iv] In Carter’s version of the events that day, the Johnsons demanded that Nixon reveal who he voted for in the primary.

The possibility that these attacks were directly related to punishing Nixon and Carter for exercising their right to vote prompted the Atlanta FBI field office to begin a formal civil rights violation investigation. Edwin J. Foltz, Special Agent in Charge for the Atlanta office, sent the completed case report in a memo to J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, on September 13th. Foltz suggested in the memo that the information furnished by Carter could be “possibly part of an overall conspiracy.”[v] Foltz’s use of the term conspiracy was likely a purposeful reference to Section 241 of the United States Code; one of only two criminal sanctions the U.S. Department of Justice had at its disposal to punish civil rights violations.[vi] With a preliminary report completed, the go-ahead for any further action would have to come from the FBI Director himself.

The power to open a full-blown civil rights investigation did not rest solely with Hoover. In instances of a possible violation of the Federal Criminal Code, the FBI had the responsibility to conduct a preliminary investigation “upon its own motion,” but those reports were required to be sent to the Attorney General for further evaluation.[vii] The Attorney General would make the final decision as to whether a case should be prosecuted by the U.S. Attorney’s office based on the FBI’s findings. Within a day of receiving the case report from Atlanta, Hoover sent it, along with two memos, to the Assistant Attorney General, Alexander M. Campbell. Hoover, however, made a significant change in his memo compared to the memo sent by Atlanta. All mention of the possibility of a conspiracy was gone. Instead, Hoover mentioned that Campbell “may desire to consider these complaints together” at the very end of his memo about Nixon.[viii] Since neither of the Johnsons nor Wilson were police officers, and thus not “acting under color of law” as required by statute 242, the DOJ was left with only federal statute 241 with which to prosecute the cases.[ix] Yet Hoover didn’t even suggest the possibility of conspiracy— a specific intentionality behind the Johnson’s act the FBI would need to prove in order for this case to fall under federal jurisdiction.

Hoover’s reluctance to push for a federal pursuit of Nixon and Carter cases could be traced back his personal views of race and the civil rights movement. His upbringing may be one of the sources of such reluctance. Hoover was born in 1895 in Washington, D.C., where segregation was not just the norm, it was “respectable.”[x] Hoover grew up in a country that embraced segregation as the American way of life. However, he was a very private man, and very little official record exists that clearly outlines Hoover’s personal views on race.

It is possible to look at Hoover’s actions as director of the FBI for evidence that even if Hoover did not pronounce himself to be a white supremacist, he had unfavorable views toward the civil rights movement. Hoover attempted to undermine the credibility of the civil rights movement by insisting it had been incited and infiltrated by communists. Both communist and black activists alike were labeled as subversives, posing a threat to the American way of life through racial unrest.[xi] Playing on the fears of the white American public was only one tactic Hoover used to avoid involvement in civil rights issues.

Hoover was also argued for state jurisdiction over federal jurisdiction in these cases. Hoover maintained they were not civil rights violations but instead racial violence cases. In a letter to Attorney General Tom Clark in September 1946, Hoover expressed frustration that his bureau’s time was being wasted on investigating cases that did not actually violate federal statutes related to civil rights.[xii] Hoover charged that allegations of civil rights violations often involved a private citizen acting against another private citizen, and thus it was the responsibility of the state government to uphold State laws.[xiii] Hiding behind the limited crimes prohibited by federal criminal statutes for civil rights violations allowed Hoover to skirt involvement in civil rights cases.

Tom Clark responded to Hoover’s letter writing:

“…There is no question but that a large percentage of investigation[s] initiated in this field prove in the end to be fruitless, but in each case the complaint made is indicative of the possibility of a violation, and if we do not investigate we are placed in the position of having received the complaint of a violation and of having failed to satisfy ourselves that it is or is not such a violation.”[xiv]

Clark conceded to Hoover’s argument about how infrequently the cases proved to be the Department of Justice’s responsibility, and yet still insisted that the FBI investigate each allegation of a civil rights violation. Clark, however, only insisted that the DOJ must “satisfy ourselves” that the cases are not a violation. The ambiguity as to what constituted satisfaction gave Hoover leeway to claim FBI dissatisfaction with the cases as a way to follow his personal prejudices.

Clark himself was hesitant to pursue a federal investigation. On September 28th, Assistant Attorney General Alexander M. Campbell, wrote in a memo that the DOJ was originally inclined to defer to the ongoing state prosecution. It seems that Clark and Campbell were satisfied with Hoover’s opinion of the cases as not a violation of the U.S. Code. Campbell, however, wrote that Henry H. Durrence, the Assistant U.S. Attorney in Savannah, was not yet satisfied. Durrence expressed his desire for a more thorough federal investigation, leading Clark to request further investigation from the FBI into the Nixon and Carter cases. [xv] Clark handed the reins of the federal investigation over to Henry H. Durrence, the only one unsatisfied as to whether the case should be left to state jurisdiction. However, by September 30th, Durrence called off federal investigation into the Nixon case in favor of the ongoing state prosecution in the Montgomery Superior Court. [xvi] Within less than three weeks from the creation of the first official FBI case report on these cases, all federal investigations had come to a halt.

On November 4, 1948, the prosecution for the murder of Isaiah Nixon by Mr. N. G. Reeves of Johnnie Johnson and Jim A. Johnson led to a verdict of not guilty for Jim A. Johnson and nol prosse for Johnnie Johnson.[xvii] With the close of the trial came the end of all prosecution sought by the state, and yet the Carter case had not even been brought to trial in the Superior Court. On December 17, 1948, Clark reopened the FBI investigation into the Carter case. If the attorneys prosecuting for the state wouldn’t ask for an investigation, the FBI would have to step in.

By February 25, 1949 Special Agents Donald L. Kimble and Bruce B. Greene produced a second case report on the Carter case. This report is much more thorough than the first FBI report from September. Special agents Donald L. Kimble and Bruce B. Greene collected statements from 16 different people besides Dover Carter, unlike the first report from September 13th that included just one statement.[xviii] In a letter on February 2, 1948, however, Durrence cited statements from only four of these 16 statements in a letter to the Attorney General’s office. [xix] He was satisfied that the contradictory statements provided by Johnnie Johnson, Thomas Wilson, and two passengers in the car with Carter when he stopped that day were evidence that “a successful prosecution could not be maintained… and no further investigation is warranted.”[xx] Campbell formally closed the federal investigation into the Carter case on March 7, 1948.[xxi]

The following day, March 8, 1949, Clark requested that the trial of the Johnsons for the Nixon case be reopened by the FBI since “Nothing in [DOJ] records indicate whether the prosecution was bona fide… Further we have not had the statement of any eye-witness.”[xxii] In contrast to the FBI’s second investigation of the Carter case, the second investigation into the Nixon case produced much less evidence in part because of Campbell’s requests for the investigation. Despite having no witness statements taken by FBI field agents, Campbell limited the request to just “interviews with the State prosecuting attorney or other official familiar with the trial in the State court and to an interview with the widow of the victim.”[xxiii] SAC Bruce B. Greene interviewed a total of five witnesses: Sallie Nixon, widow of the victim; J. H. Peterson, superior court clerk for Montgomery County; Judge Eschol Graham; N. G. Reeves Jr., attorney acting as Solicitor pro tem during the trial; and finally Ella Mae Frye. Judge Graham recalled that three attorneys were in charge of prosecuting the case—N. G. Reeves, Fred T. Lanier, and William H. Dampier—and that the case was “ably presented.”[xxiv] Reeves shared Graham’s opinion, again stating that the case was ably presented.[xxv] Based primarily on the statements of these two men, as they were the only statements that gave information about the trial itself, Attorney General Tom Clark was satisfied that the case had been fairly tried and ordered the matter closed on April 29, 1949.[xxvi]

Neither the state prosecution, nor the federal investigations of 1948-1949 resulted in convictions for the men accused of the murder, the assault, or the alleged civil rights violations of Isaiah Nixon and Dover Carter. With the completion of the first formal case report, SAC Edwin J. Foltz gave the first indications of the possibility of a federal prosecution under statute 241 of the U.S. Code. By the time J. Edgar Hoover passed this case report on to Tom Clark however, any mention of a conspiracy had fully disappeared. From that moment on, the driving force in the federal actions surrounding the Carter and Nixon cases was Hoover’s desire to have nothing to do with them. Attorney General Tom Clark only minimally resisted Hoover’s wishes, insisting that an FBI investigation must be completed, but only to the DOJ’s satisfaction. Henry H. Durrence, Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Savannah District, resisted only slightly more. Yet Durrence eventually agreed that the prosecution of the cases was best left to state jurisdiction. Hoover used limited federal statutes on civil rights violations, as well as the ambiguous direction of Tom Clark, to his advantage in an attempt to avoid investigative responsibility in civil rights. This ultimately led to the federal governments’ failure to bring the men responsible for these crimes to justice.

Edited by David Beasley

[i] Thomas A. Erwin Jr., “Johnnie Johnson; Thomas Wilkes; Claude Sharp; Jim A. Johnson; Dover V. Carter, Victim; Isaiah Nixon, Victim” September 13,1948, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[ii] For clarity purposes, the alias “Thomas Wilkes,” used in early FBI files on the case, has been the corrected to Thomas Jefferson Wilson. This corrected version of Wilson’s name is first used in the document: Bruce B. Greene, “’Changed’ Johnnie Johnson, WA Johnny; Thomas Jefferson Wilson, WA Thomas Wilkes; W. Claude Sharpe, WA Claude Sharp; Dover V. Carter, AKA Dovie Carter, Dobbie Carter-Victim,” January 25, 1949, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[iii] Erwin Jr., “Johnnie Johnson;…” September 13, 1948, 4.

[iv] Thomas A. Erwin Jr., “Johnnie Johnson; Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon – Victim” September 20,1948, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[v] FBI Atlanta field office, memo to Director of FBI and SAC (Savannah) on Johnnie Johnson, Thomas Wilkes, Claude Sharp, Jim A. Johnson, Dover V. Carter, Victim, Isaiah Nixon, Victim. September 13, 1948, 1, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon

[vi] The federal statutes that applied to civil rights violations are discussed in O’Reilly. Two statutes, Sections 241 and 242 of Title 18 of the Federal Criminal Code, provide criminal sanctions of up to 10 years in jail and a $5,000 fine against two or more persons who conspired to deprive citizens of their constitutional rights (241) or a misdemeanor for local government officials who deny citizens their civil rights under “color-of-law,” (242). However since 241 required proof of conspiracy by two or more people, and 242 required the specific intent to deny civil rights, these statutes were largely ineffective at providing a specific charge for which the DOJ could charge private citizens.

[vii] Kenneth O’Reilly, “Racial Matters”: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960-1972, (New York: The Free Press, 1989), 33.

[viii] J. Edgar Hoover, FBI, memo to Mr. Alexander Campbell, Assistant Attorney General, on Johnnie Johnson; Thomas Wilkes; Claude Sharp, Dover V. Carter – Victim, Civil Rights and Domestic Violence. September 14, 1948, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[ix] The FBI defines acting under color of law as a person using authority given to them him or her by a local, state, or federal government agency. The FBI self-identifies as “the lead federal agency for investigating color of law abuses, which include acts carried out by government officials operating both within and beyond the limits of their lawful authority.” “Color of Law Abuses.” The FBI: Federal Bureau of Investigation. FBI, n.d. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.

[x] O’Reilly, “Racial Matters”, 10.

[xi] O’Reilly, “Racial Matters”, 13.

[xii] J. Edgar Hoover, “Letter of September 24, 1946 from J. Edgar Hoover to the Attorney General (File No. 144-012.), Documents related to the “President’s Committee on Civil Rights” in the Harry S. Truman Library.

[xiii] O’Reilly, “Racial Matters”, 28-29.

[xiv] Tom C. Clark, “Reply, dated September 24, 1946; Attorney General to J. Edgar Hoover,” September 24, 1946, Documents related to the “President’s Committee on Civil Rights” in the Harry S. Truman Library.

[xv] Alexander M. Campbell , memo to The Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation on Johnny Johnson, Jim A. Johnson, Thomas Wilkes, Claude Sharp; Isaiah Nixon and Dover V. Carter – Victims; Civil Rights and Domestic Violence, September 28, 1948, 1, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xvi] Ibid, 2, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xvii] Bruce B. Greene, “Johnnie Johnson; Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” January 1, 1948, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xviii] Bruce B. Greene, “’Changed’ Johnnie Johnson, WA Johnny; Thomas Jefferson Wilson, WA Thomas Wilkes; W. Claude Sharpe, WA Claude Sharp; Dover V. Carter, AKA Dovie Carter, Dobbie Carter-Victim,” January 25, 1949, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xix] Henry H. Durrence, memo to The Attorney General re; Johnnie Johnson, alias Johnny; Thomas Jefferson Wilson, alias Thomas Wilkes; W. Claude Sharpe, alias Claude Sharpe, Dover C. Carter, alias Dovie Carter, alias Dobbie Carter-Victim, February 2, 1949, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xx] Durrence, memo to The Attorney General re; Johnnie Johnson…, February 2, 1949, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xxi] Alexander M. Campbell, memo to Director of FBI on Johnnie Johnson, wa Johnny; Thomas Jefferson Wilson, wa Thomas Wilkes; W. Claude Sharpe, wa Claude Sharp; Dover V. Carter, aka Dovie Carter, Dobbie Carter – Victim; Civil Rights and Domestic Violence, March 7th, 1949, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon

[xxii] Alexander M. Campbell, letter to Director of FBI on Johnny Johnson, Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon- Victim, March 8th, 1949, 1, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon

[xxiii] Alexander M. Campbell, letter to Director of the FBI on Johnny Johnson, Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon-Victim, March 8, 1949, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xxiv] Bruce B. Greene, “Johnnie Johnson, Jim A. Johnson, Isaiah Nixon-Victim,” March 3, 1949, 3, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xxv] Ibid, 4, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.

[xxvi] Alexander M. Campbell, letter to J. Saxton Daniel United States Attorney, April 29, 1949, FBI files on Isaiah Nixon.