| By Arianna Skibell |

The day Dawson Police Officers Weyman B. Cherry and Randolph McDonald arrested James Brazier, seemingly without warrant, was not anomalous in Southern history. When the officers walked onto James Brazier’s lawn, blackjacks in hand, they carried with them the weight of Jim Crow and the social and psychological constructs that accompanied it.

In the post-Civil War South, hierarchies of power and authority were destabilized, creating a hostile environment for black people — liberated slaves and their descendants — and laying the groundwork for the environment in which the Brazier case took place.[1] With the post-emancipation era arose a system of racial discrimination perpetuated by a small group of elite white southerners that sought to maintain their political and economic power. This desire for political dominance was coupled with the ideology of white supremacy, which many defended with dogmatic vigor.[2]

A greater understanding of the forces and context that facilitated James Brazier’s death can be gained through an examination of the psychological basis of white supremacy and the effects of these principles in Southern society during the Jim Crow era. White supremacy functioned as a societal structure that emphasized the inherent inferiority of black people, while reinforcing the superiority of whites. The origins of white supremacy can be traced back to emancipation,[3] however the development, reinforcement and psychological effects of such a social structure is harder to understand.

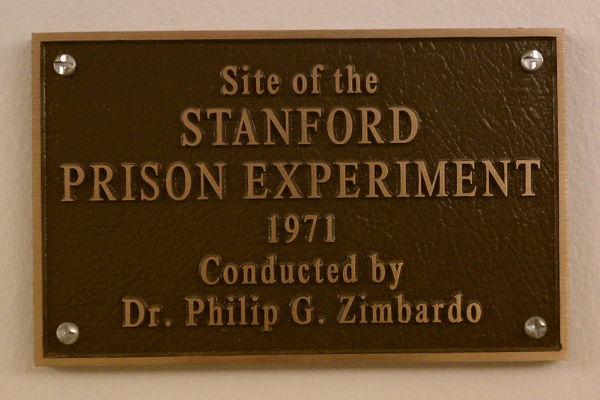

Plaque marking the Stanford Prison Experiment on the campus of Stanford University, photo courtesy Brandon Burke

In 1971, Professor of Psychology at Stanford University Philip Zimbardo sought to gain a greater understanding of human relations and hierarchies of power. He selected 24 male students to participate in his study. He randomly assigned half to the position of “guard” and half to “prisoner.” Zimbardo arranged for police to arrest the “prisoners” and bring them to the basement of the Psychology building, which had been remodeled as a prison. Within a day, the guards, who wore uniforms, became oppressors and predators of their own classmates. They used shame, sexual humiliation, verbal abuse, and other tactics to suppress prisoners. The extreme abuse and lack of an escape for the prisoners created a sense of hopelessness and a loss of identity. The experiment was scheduled to span two weeks, but Zimbardo cancelled it after six days. Zimbardo admitted he was so wrapped up in his position as “warden” of the prison that it took an outsider, a graduate student named Christina Maslach, to convince him to terminate the study.[4]

The results of Zimbardo’s experiment led him to delineate an important phenomenon in human psychology: All that is necessary for ordinary individuals to become predatory and violent is “a group structure that permits and encourages the scapegoating and dehumanization of one subgroup by another.”[5] Zimbardo’s students returned home after six days. The victims of the white supremacist South, on the other hand, lived in a similar environment with no reprieve.

The Jim Crow South was a societal, large-scale example of the phenomenon Zimbardo defined. Black people were considered second-class citizens, and many faced persecution and abuse from law enforcement. James Brazier was no exception. Before Cherry took Brazier to jail, witnesses reported he beat Brazier severely,[6] at one point pulling out his pistol and striking him in the stomach. Cherry said, “I oughta blow your goddam brains out,” kicked Brazier twice in the groin and slammed the car door on his leg before driving off.[7]

One crucial component of white supremacy that produced notable psychological effects was the system of racial etiquette, a form of Social-interaction Theater. Racial etiquette outlined the way blacks were to speak, gesture, and even gaze in an interracial setting. Black people adhered to these rules not out of a feeling of inferiority, but rather as a survival tactic, as the consequences of breaching the dictates of racial etiquette often included verbal and physical rebuke.[8]

Hattie Bell Brazier, James Brazier’s wife, recounted that Brazier was driving home from church when he saw an officer had pulled over his father, Odell Brazier. The officer had started to beat Odell Brazier with a blackjack. The younger Brazier told Officer Randolph McDonald to stop hitting his father. [9] This command can be seen as a breach of racial etiquette. Black people were expected to mind their own business and not interfere with a white man’s affairs, especially not a white police officer.

This violation arguably led to the James Brazier’s murder. The night he was taken to the Terrell County Jail, Cherry and McDonald, and possibly others, woke Brazier up and told him, “Come on boy, go with us.” Brazier responded, “Wait until I get my shoes,” to which the officers replied, “You don’t need no shoes.”[10] The next morning when Brazier was taken from his cell, he was unable to support himself, he could not talk or walk, and he was covered in blood.[11] Five days later, James Brazier died; his skull had been crushed.[12]

James Brazier’s murder is one example of the crimes committed against black people in the Jim Crow South; and these lawless murders had tremendous consequences. It is well documented that stress associated with racism negatively affects the mental health of African Americans;[13] however, the mental distress that arises from experiencing racism can also be felt through the collective memory of slavery and the Jim Crow era.[14] This phenomenon is called Segregation Stress Syndrome (SSS).

The symptoms of SSS are “the chronic, enduring, extremely painful responses to the total institution of Jim Crow which includes physical reactions such as sweating and avoidance of events that remind them of the initial trauma that occurred sometimes when they were very young.”[15] SSS is similar to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in that it results from trauma and cumulative stress, leading to potential long-term psychological consequences.[16] However, PTSD tends to affect individuals in different ways depending on the trauma that occurred; whereas SSS results from sustained traumatic events, including lynchings, sexual violence, Klan attacks, and killings. SSS can also affect those who share a culture and intergenerational knowledge of the abuse. Because the collective and historical trauma is cumulative, African Americans in the 21st century are predisposed to suffer from SSS.[17] The murders and violent attacks, much like that of James Brazier, reared a community to act, think, and cope in a way that has transcended generations and continues to affect the well-being of African Americans.

The murder of James Brazier did not occur in a vacuum, but was facilitated by the dogmatic belief in white supremacy and the dehumanization of blacks that occurred as a result. His death was abetted by the strict rules of racial etiquette that enabled whites to maintain a sense of superiority – Brazier broke those rules and lost his life as a consequence. The psychology of the era, and the consequences that persist must be comprehended in order to contextualize and begin to understand the murder of James Brazier.

— Edited by Danielle Wiggins