| By Nathaniel Meyersohn & Hannah Coleman |

On April 23, 1958, Odell Brazier appeared at the FBI’s field office in Atlanta. His son, thirty-two-year-old James Brazier, lay in critical condition in a Columbus, Georgia, hospital after suffering a brutal beating at the hands of local law enforcement officials following his arrest three days earlier. The elder Brazier furnished a signed complaint to FBI agents alleging that Dawson, Georgia, officers Weyman B. Cherry and Randolph E. McDonald assaulted Brazier while in custody at the Terrell County jail.[1] Following the interview, Atlanta Special Agent in Charge Nathaniel R. Johnson, Jr. ordered a preliminary investigation into Brazier’s complaint.[2]

The investigation of James Brazier’s death was immediately complicated by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s attitudes toward civil rights, FBI protocols regarding these types of investigations, and state laws governing the working relationships between federal and state authorities. Hoover, a longtime antagonist of the civil rights struggle, believed that communist influence had pervaded the movement, and considered civil rights investigations to be “fishing expeditions.”[3] The director, sympathetic to Jim Crow racial customs and states’ rights, resisted sending FBI agents “rushing pell-mell into cases” of racial violence.

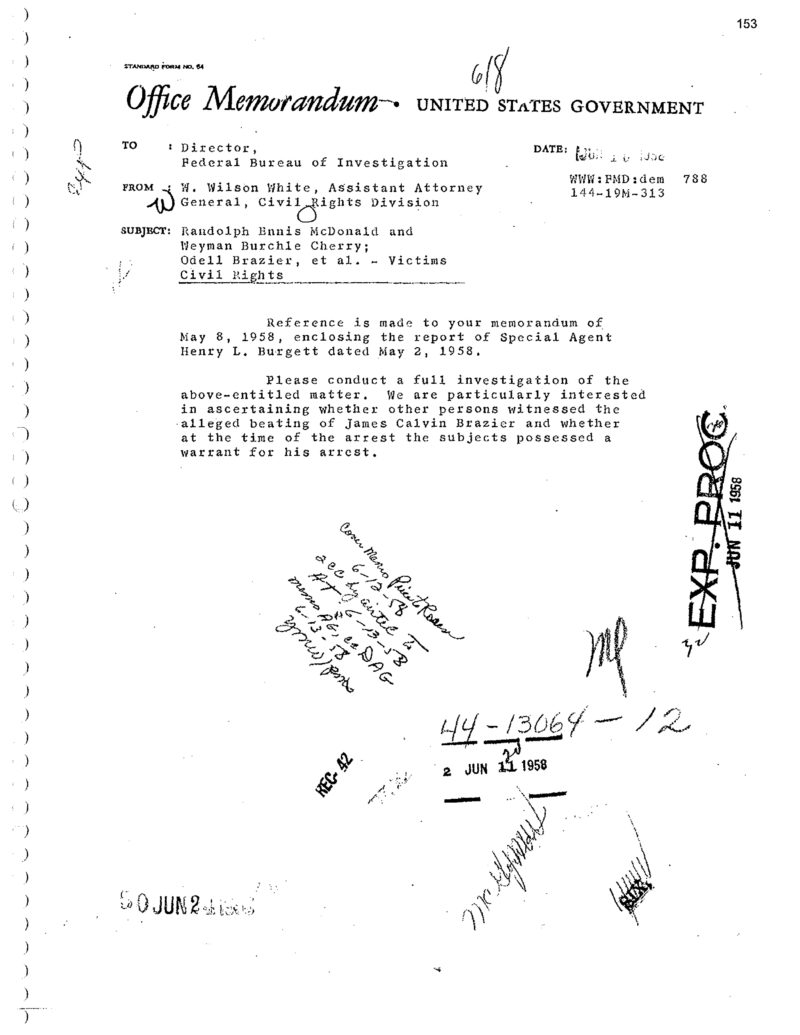

On June 10, 1958, two days after The Washington Post story exposing police brutality in Terrell County, the head of the newly-created Civil Rights Division in the Justice Department ordered the FBI to conduct “a full investigation.” Document from the FBI file on the James Brazier case.

When the FBI was compelled to send agents to investigate civil rights violations, federal policy dictated the implementation of a preliminary investigation into citizens’ complaints.[4] The Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice was responsible for ordering full investigations into potential violations—a step that could delay the investigative process.[5]

If the Civil Rights Division requested a full inquiry, FBI policy required federal agents to work in close cooperation with local law enforcement officials during the investigation. Agents were obliged, for example, to notify the heads of local enforcement agencies when subordinate officers were under investigation. In 1958, Georgia law also included the extraordinary requirement “that a member of the prison staff be present when a complainant prisoner is being interviewed by an FBI agent.”[6] Since FBI agents were prohibited from interviewing witnesses in the absence of prison officials, the Georgia statute empowered local officials to terminate witness interviews before the circumstances surrounding possible crimes could be discovered.

In view of the fact that FBI agents were not allowed to remove prisoners from county jails to conduct private interviews, potential witnesses were also vulnerable to various forms of intimidation.[7]

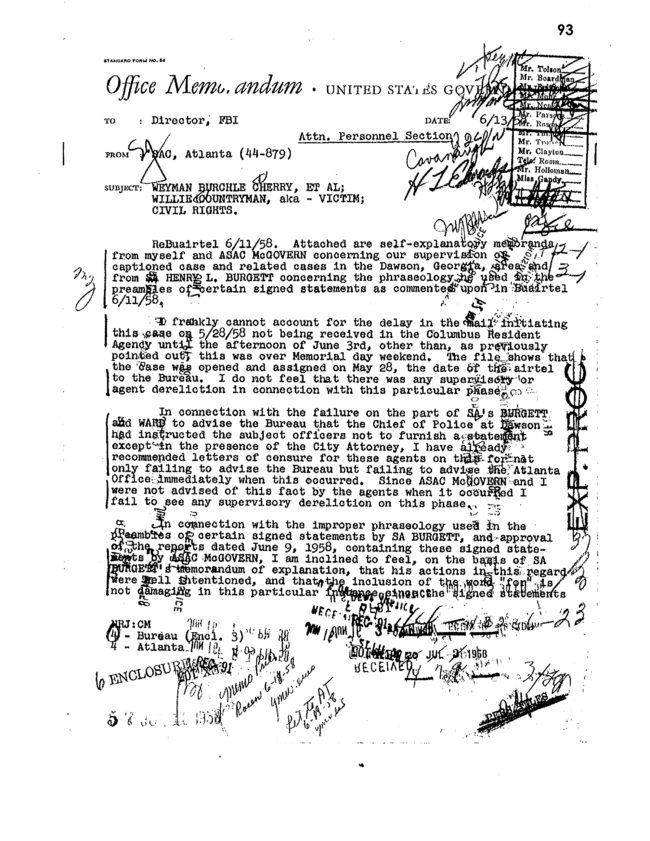

The FBI Special Agent in Charge in Georgia devoted considerable time responding to scolding from Hoover’s office over seemingly minor infractions. The memo was routed throughout FBI headquarters a dizzying number of times. Document from the FBI file on the James Brazier case.

The FBI investigation into James Brazier’s murder—which expanded a month later when Dawson police killed another black man, Willie Countryman—was one of the first cases to land at the newly-created Civil Rights Division, a unit of the Department of Justice established by the 1957 Civil Rights Act. The Civil Rights Division would grow over the next five decades into the federal government’s most powerful institutional force in criminal and civil attacks on discrimination in voting, housing, employment, education and other arenas of public life. But correspondence between the Division and the FBI in the Brazier case—as well as in the Countryman investigation— reveal early stutter steps, divergent approaches to the cases, and tension between the two agencies as the Division and the FBI headquarters struggled to gain traction in the cases. Memos within the FBI suggest annoyance in Hoover’s office with the performance of the Georgia agents, often over minor procedural issues.[8]

Despite the bureaucratic and legal hurdles, Special Agents James Ward and Henry Burgett initiated a preliminary investigation. The two agents visited Dawson the day after Odell Brazier visited the FBI office in Atlanta and conducted interviews with local residents who had witnessed events surrounding Brazier’s arrest and incarceration. The agents interviewed officers Cherry and McDonald; Dr. Charles M. Ward, who had examined Brazier while in police custody; Dr. John D. Durden, who had performed surgery on Brazier after police beat him a second time; Brazier’s widow, Hattie Bell Brazier; and neighbors James Latimer and Lucius Holloway.[9] Mrs. Brazier and Latimer signed statements testifying that Cherry assaulted Brazier with his blackjack after Brazier objected to the officers’ appearance at the Brazier’s home. Mrs. Brazier also charged that Cherry struck Brazier in the face with his gun and kicked him.[10] About a week after James Brazier died of his injuries on April 25, Burgett submitted the results of the preliminary investigation. Six days later, the Bureau sent the report to the new Civil Rights Division, which would determine if a full investigation was necessary.[11]

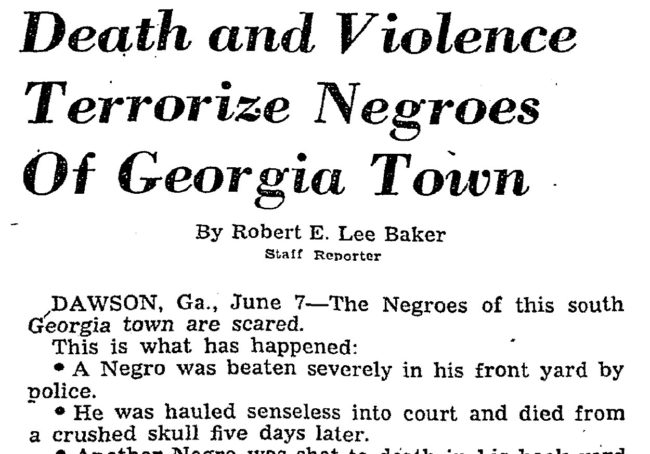

The Washington Post picked up the Brazier story and published an article with this pointed headline. The Washington Post and Times Herald, June 8, 1958.

The FBI had taken no further action on the case when, on June 8, The Washington Post and Times published a front-page article, “Death and Violence Terrorize Negroes of Georgia Town,” by reporter Robert E. Lee Baker. The story, which had a Dawson dateline, offered a scathing survey of systematic racial violence in southwestern Georgia, particularly at the hands of local law enforcement and detailed the Dawson Police Department’s repeated allegations of brutality against several local blacks, including Brazier.[12] “The Negroes of this [South] Georgia town are scared,” Baker wrote.[13] The presence of federal law enforcement looking into the racial violence provoked the particular ire of Dawson Police Chief Howard Lee. “These FBI men investigating everything aggravates me,” he complained to the reporter. “It aggravates me worse because the FBI starts talking to niggers and then the niggers get to thinking they’re important and it stirs them up.”[14] Chief Lee’s attitude reflected a common fear among white southerners that federal intervention in local affairs would upset the prevailing racial order.[15]

The article alarmed FBI and the Civil Rights Division officials, generating a flurry of memos inquiring about the status of the FBI’s investigation. Soon after the Post article, Civil Rights Division lawyers moved to deflect criticism of the Justice Department’s inaction on the Brazier case. Assistant Attorney General W. Wilson White, who recently had been named head of the Civil Rights Division, issued a formal request for a full investigation of Brazier’s death.[16]

The day after the Post published Baker’s story exposing the police brutality — and while the Civil Rights Division was inquiring about the status of the FBI investigation — Hoover’s office and Nathaniel Johnson, the Special Agent in Charge of the FBI office in Atlanta, began to exchange memos about FBI agents’ technical mistakes.[17] The agents, in turn, found themselves tied up typing up their responses and dealing with the prospect of censure during a critical time in the investigation.

Agents Maurice Foshee and Henry L. Burgett returned to Dawson in late June for a five-day period to conduct a series of interviews. The two agents’ interviews with prisoners in the Terrell County jail during the third week of June proved revealing. Inmate Marvin Goshay recalled that he first saw Officers Cherry and McDonald place Brazier in his cell around 6:30 p.m. The officers removed Brazier from his cell around 10:30 p.m., Goshay told FBI agents. When Brazier attempted to put on his shoes and coat, the officers replied ominously that he would not need them. Goshay also recalled how a Dawson police officer asked him to assist a bloody and battered Brazier from his cell to his court date the next morning. Jail cook Nettie Cate told the agents that she witnessed the officers remove Brazier late that evening. When Cate saw him again later that morning, Brazier had been placed in a cell in the women’s cellblock, where a police officer periodically tried to revive the unconscious man.

Other witness testimonies proved less helpful. Eugene Magwood, the jail trusty,[18] denied having any information related to the events that evening. Magwood told FBI agents that he did not see Brazier until the morning of April 21, when Brazier left his cell unassisted. When the FBI agents attempted to interview Mary Carolyn Clyde, Magwood eavesdropped on the conversation, ostensibly to convey any incriminating evidence to the officers under investigation and to intimidate Clyde; she also said spies were placed in the cell adjacent to hers to pick up all of her conversations, heightening her apprehension about disclosing her account.[19] FBI agents returned to Dawson on August 1 to re-interview Clyde. But Sheriff Mathews insisted that the agents conduct this interview in his office, and he attempted to intimidate Clyde by interrupting the interview three times. Abruptly, he ended the session before Clyde had the opportunity to sign a statement.[20]

On August 4, 1958, more than three months after James Brazier died, Joseph H. Davis, the Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Middle District of Georgia, asked a federal grand jury in Macon to bring indictments against Officers McDonald, Cherry, and Edwin Jones in connection with Brazier’s death. Davis relied heavily upon the restricted investigative work of FBI agents in Dawson to prove the government’s case against the three officers. After three days of sworn testimony, the grand jury returned a verdict of “no bill,” indicating that the body did not believe there was enough evidence to issue an indictment against the officers.[21] Due to the secretive nature of the grand jury deliberative process and the absence of historical records of the proceedings, it is difficult to assess the extent to which the difficulties surrounding the FBI’s investigation inhibited the prosecution of Officers Cherry and McDonald. Jim Crow juries were reticent to indict—much less convict—white officers for abuses of African Americans. Still, the FBI’s investigation, hampered by FBI protocols and local intransigence, likely thwarted the search for justice in the death of James Brazier. In 2006, when the Department of Justice announced its civil rights “Cold Case Initiative,” it included the Brazier case among those it said the FBI would reopen and reexamine. In April 2009, almost exactly 51 years after James Brazier was arrested and beaten, the FBI closed the case, saying it had determined that Cherry and McDonald were responsible for Brazier’s death, and that both of the police officers had died and could not be prosecuted. The Brazier case would join the annals of unsolved cold cases during the troubled civil rights era.

Edited by Brett Gadsden and Hank Klibanoff

In the Truman Committee’s landmark study, To Secure These Rights, it found “evidence that FBI investigations [of civil rights cases did not measure] up to the Bureau’s high [standards]” and that the FBI often felt that it was “burdensome and difficult” to conduct these inquiries. The committee also asserted that “cumbersome administrative relationships” between the Bureau and the Department of Justice blocked streamlined investigations.

Georgia, South Carolina and Florida were the only states that had this law in the 1950s.

While the agents began conducting interviews on April 23, when James Brazier was still alive, they did not begin dictating their notes until April 26, after Brazier died, and did not write their reports until May 2. So in some instances, the agents’ reports appear to not know Brazier died when the agents almost certainly must have known.

“Confidential Report re: Investigation of Terrell County, GA,” Papers of the NAACP, (microfilm, Robert W. Woodruff Library), Part 25, Series D, June 9, 1958.

The memos came from “Director, FBI” without additional attribution. The memos from the Atlanta SAC to “Director, FBI” went as far up the line as Clyde Tolson, deputy director of the FBI, routing check marks on the memos indicate. Whether the person responding as “Director, FBI” was Hoover, Tolson or someone else is difficult to discern. The mistakes: Agents had not immediately told supervisors that Chief Lee instructed Cherry not to speak with agents without a city attorney present; they had not anticipated that a holiday might delay mail and bust a deadline; they had told witnesses their testimony could be used “for or against” them when they should not have said testimony might benefit the witnesses; and an agent who recommended a clerical employee for a commendation let the employee know and asked her to type up his recommendation of her.