| By Mary Claire Kelly |

Little more than a month after he brutally and fatally beat James Brazier, Police Officer Weyman Burchle Cherry was still on duty, patrolling the black neighborhoods during the night shift in Dawson, Terrell County. At about 1:30 a.m. on May 24, 1958, he and his partner Robert Terrell Hancock walked onto the property where 32-year-old Willie “Wootie” Countryman, a truck driver and Army veteran, lived with his grandmother. There, in the backyard, Cherry encountered Countryman. In what Cherry said was self-defense, and others labeled as murder, Officer Cherry shot Countryman in the abdomen and killed him.

Cherry later said he and Hancock been had investigating a “loud hollering and hooping”[1] in the neighborhood when a drunk Countryman jumped out from behind a tree in his backyard and attacked the officers with a knife – an account that friends and family of Willie Countryman contradicted at every step. Countryman’s girlfriend said she and Countryman were sitting on the porch talking when they heard a noise around the side of the house. In her account, an unarmed Countryman went to investigate, only to encounter Cherry, who shot him. Countryman was not known to carry a knife, the family insisted, and the trees in the backyard were so small no one could hide behind them. Cherry told FBI investigators that Countryman had cursed at the police officers and lunged at him, nicking his police cap with the knife. Seeing that Countryman was preparing to strike again, Cherry said, he fired his pistol at Countryman, hitting him in the stomach. Countryman toppled over and his head landed on top of the hat that had been knocked from Cherry’s head. The hat and the knife in Cherry’s story would prove to be problematic as evidence.

Cherry told FBI investigators that he and Hancock sent for Police Chief Howard Lee and an ambulance. Lee, commenting a month later in The Washington Post on the surge in the number of black men killed or assaulted by white police officers in Dawson, expressed surprise at one aspect of Countryman’s death: “I remarked on the way to the hospital how quick he died. I had to shoot one in the stomach a few years ago and he lived five or six days.”[2]

The ambulance took Countryman to the Dawson hospital, where Dr. Charles Ward pronounced him dead on arrival. Ward, who conducted autopsies for the county, would later tell investigators that “the odor of moonshine whiskey was quite prominent”[3] in Willie Countryman’s abdominal fluid during the autopsy. Ward is the same doctor who a month earlier had tended to James Brazier in the Terrell County Jail after Officer Cherry had beaten Brazier; in that instance, Ward misinterpreted James Brazier’s slurred speech and blood in his ear and nose. He had concluded that Brazier was merely drunk when, it turned out, he was suffering a skull fracture that needed immediate medical attention in a hospital. The day after Ward’s autopsy of Countryman, a coroner’s jury declared that Cherry was acting in the line of duty and in self-defense when he shot Countryman.[4]

Members of Dawson’s black community, especially those who knew Countryman, did not buy the official police account of events. Countryman had never been known to be violent or carry a knife, they said.[5] The knife that Countryman had, in official accounts, brandished at Cherry was an elusive piece of evidence. Cherry had described it as nine inches total with a five-inch saw blade and a bottle opener on the handle. The coroner’s jury was presented a dull “switchblade knife 10 to 12 inches long when open” with the point broken off, and a handle that appeared to have once been painted brown or black.[6] The coroner jury’s report made no mention of any bottle opener on the handle.

Harrison Powell, who worked at the local black funeral home, told the NAACP field secretary, Amos Holmes, that he saw a knife when he arrived at the scene to assist with the ambulance. He later told investigators he noticed a knife on the side of Countryman’s body when it was on the ambulance cot. Powell said he saw an officer pick up the knife, which was, including both the blade and the handle, about six inches long—half the size of the knife the coroner’s jury saw.[7]

When investigators later asked Cherry to produce the knife he had claimed Countryman wielded, Cherry said he could not find it. He told investigators he “must have left it at home.” He also could not give investigators the cap cover that he said Countryman had cut because, he said, he had had it cleaned. The Dawson law enforcement officer, who by nature of his profession should have known basic investigative procedures, said he “guessed he should have left it as it was in order that they could have seen the dirt on the cover.”[8]

The black men and women who had known Countryman had other reasons to doubt the officers’ story. Countryman did not seem like the kind of man to attack a police officer without provocation, they said. Friends called Countryman a “steady worker and a well respected, quiet man in that community,”[9] with a good reputation among both whites and blacks. He had never been involved in civil rights activity. Even Police Chief Lee, in his own white supremacist vernacular, found a way to say nice things about the victim. Countryman had “only been arrested twice before,” Lee said, and “seemed to be a good nigger.”[10]

Countryman had also not been known to be a heavy drinker. Leaner Williams, Countryman’s neighbor, told FBI agents that Countryman “would take a drink but to her knowledge he had never been drunk.”[11] His grandmother, Cornelia Countryman, later told investigators she had been with Countryman before she saw him go to bed that night and she had only seen him drink water. [12] Neighbors said there had been no suspicious noises in the neighborhood that night. They noted to investigators that the yard where Countryman lived had only two trees—a peach and a pecan tree—neither of which was large enough for a grown man to hide behind.[13]

The death of Countryman was just one incident in a rash of police violence against Terrell County blacks over several months. On May 23, two days before Countryman’s death, Cherry had shot Tobe Latimer in the buttocks, sending him to the hospital. Nearly a month earlier, Cherry and his partner Randolph McDonald had arrested and beaten James Brazier in front of a neighborhood of witnesses. Black men and women still remembered how, in 1956, police had beaten a man named Frank Burks so violently that they flayed off parts of his skin. Three or four years earlier, police had thrashed “Brother” Martin for honking his car horn in front of the local theater. Anonymous black community members told investigators that Chief Lee had killed at least two black men in recent years and McDonald had beaten at least six.[14]

In a county where African-Americans made up two-thirds of the population, yet only represented about 1% of registered voters,[15] Dawson law enforcement officers intimidated black men and women through the constant threat of violence. Killings and beatings bolstered local practices that limited blacks’ rights, which included an 11 p.m. curfew within city limits.

Hours after Cherry killed Countryman, Dawson city police arrested a young black man named Billie Flagg. Policeman Harold Jones had driven by Flagg and others playing on a Dawson baseball field at around 9 a.m. As the police cruiser rolled by, Flagg allegedly made a hand gesture like he was shooting at the officer and tutted a machine gun-like noise. Jones whipped the car back around, walked up to Flagg, and smacked the 21-year-old. Jones searched Flagg and hit him again before taking him to jail. When the young man’s mother, Annie Flagg, came to the Terrell County jail to ask about her son’s arrest, she was also thrown in a cell.

“She was carrying on about her boy being locked up,” Chief Lee later explained in an interview. “We put her in there to cool her down.”[16]

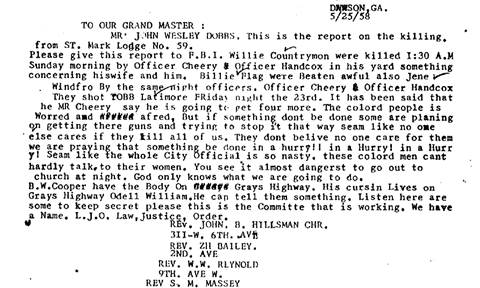

Later that day, a small group of leading black citizens calling themselves Law, Justice, Order, or L.J.O., met to address the morning’s events. In just a few hours, news about Countryman and Flagg had spread around town, and the members of L.J.O knew they had to ask for outside help quickly, before somebody else got hurt. They had heard that Cherry had said he was going to “get four more.” They hastily wrote a letter to John Wesley Dobbs, a leading political leader in Atlanta, to furnish to the FBI.:

“The colord people is worred and afred, But if something don’t be done some are planning on getting there guns and trying to stop it that way seam like no one else cares if they kill all of us. They don’t believe no one care for them we are praying that something be done in a hurry!! In a Hurry! In a Hurry!”

They said it felt dangerous for black people to even go to church at night. At the end of the letter, they signed their names and added a postscript:

Black community members organized under the name Law, Justice, Order, or L.J.O, sent this letter to John Wesley Dobbs, political leader in Atlanta, found in FBI Files on Willie Countryman, June 9, 1958.

“PLEASE COME! PLEASE COME! PLEASE COME! WE CAN’T HOLD THESE PEOPLE MUCH LONGER.”[17]

Dobbs gave the letter to the FBI, which opened an investigation on May 28. The Bureau had been in Terrell County one month previously, to conduct a preliminary investigation into Brazier’s death. The investigation into Countryman’s death had a rocky start. It began close to Memorial Day, which meant investigators were delayed in sending information back to headquarters during the postal service holiday. The regional FBI head in Atlanta criticized Special Agents James Ward and Henry Burgett for not notifying FBI headquarters when Chief Lee told Cherry and Hancock not to give statements without the city attorney present. Cherry went on vacation until June 11, further extending the investigation until his return. [18]

Burgett also came under fire for “improper phraseology” in obtaining statements from black witnesses. Normally, a signed statement included a preamble informing the questioned witness only that he or she did not have to make a statement, and that any statement “could be used in a court of law.” For several witnesses in the Countryman and Flagg cases, Burgett told them that the statements could be used “for or against” them in court. Criticism against Burgett for what might seem to be a minor infraction came from the highest echelon, the office of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who had often expressed reluctance for the FBI to get involved in these kinds of cases. Burgett wrote a memo saying that he used the phrase in interviewing these witnesses only because “it was first necessary to gain their confidence, because they are by nature suspicious of white people, particularly law enforcement officers.”[19]

One of the witnesses with whom Burgett used this uncustomary phrase was Mary Edith Robinson, Countryman’s girlfriend. Robinson was an 18-year-old mother, living with Countryman and his grandmother. Countryman was married but separated from his wife, who lived in Tennessee. In their letter to Dobbs, the members of the L.J.O. wrote that Cherry had shot Countryman for “something concerning his wife [Robinson] and him.”

“Seam like the whole City Official is so nasty, these colord men cant hardly talk to their women,” the L.J.O. wrote. [20]

Robinson told agents Burgett and Ward that she had been there that night with Countryman. She said she and Countryman had fought on May 23 about whether or not to move, with their baby, out of Countryman’s grandmother’s house. That day, police had shown up to break up their spat, and an unnamed policeman had taken Countryman into his patrol car. Robinson watched as the policeman drove Countryman across the street to speak to two white men. After this mysterious conversation, the officer returned Countryman, but inexplicably booked Robinson in the county jail for the night instead.[21]

The next day, Robinson apologized to Countryman for the fight and asked him for money so they could go to the movies together. She told him that Officer Harold Jones had said “that if we couldn’t get along to stay away from one another and for me not to be seen back down at [Countryman’s] house.”[22] After hearing this comment, Countryman refused to go to the movies.

Later that night, Robinson took a cab to Countryman’s home, where he was asleep in bed. Neither the neighbors nor Countryman’s sleeping grandmother knew she had been at the house that night. The two were talking on the porch when they heard a noise “like someone was urinating.”[23] Countryman left Robinson to go investigate.

Robinson told investigators that she heard a falling sound, then the gunshot. She heard Countryman say, “I’m sorry I didn’t know it was you all.” She watched as one of two shadowy figures shined a light on Countryman’s body as it lay still on the ground. Then she ran away.

While FBI agents Burgett and Ward were trying to coax witnesses into talking to them, the NAACP was conducting its own investigation into the Terrell County situation. Talking to black witnesses who may have felt intimidated by the white FBI officers, NAACP field secretary Amos Holmes learned that when Robinson and Countryman fought days before the shooting, Robinson was overheard saying she “would get him.” The informants told Holmes that Robinson may have been “involved” with one of the police officers.[24] Investigators would never fully gauge the extent of Robinson’s role in Countryman’s death.

After assessing the cases in Terrell County, Holmes declared that the “situation” in Dawson was “as bad as any we have seen during our experiences in the South.” Some African-Americans even asked the field secretary to stay out of their county because it was dangerous for a black man to ride into town in a car with Atlanta tags. Many of the interviews took place in either nearby Albany or Atlanta, for the witnesses’ safety. Holmes wrote that he was worried that black men and women would retaliate in response to Cherry’s threat to “get” more men.

“This is only one of several similar powder kegs that might explode at any time,” Holmes wrote in his report to the NAACP southeastern regional office. “We will sit on it as best we can.”[25]

After talking with the Dawson community members and relatives of Brazier and Countryman, the NAACP and the Southern Regional Council decided to take action through publicity. Harold Fleming, the executive director of the SRC, fed the information about the police terror to Al Friendly, the managing editor of The Washington Post and Times Herald. When Post reporter Robert E. Lee Baker arrived in Albany, NAACP leaders introduced him to the witnesses whom he would quote anonymously in his front-page, June 8 article, “Death and Violence Terrorize Negroes of Georgia Town.”

Baker wrote about the “atmosphere of fear,” “atmosphere of indignation,” and “atmosphere of despair” permeating the small Georgia community. Baker exposed the deaths of Brazier and Countryman, and the wounding of Latimer, Flagg and others. He also described the county’s voter registration process, which denied most African-American registrants—including men and women with college degrees—their ballot.

High-profile local white leaders, including Chief Howard Lee, talked to Baker candidly about their views on race.

“We’re just as good to niggers as they’ll let us be,” Lee told Baker, a white man. “The nigger resents everything the white man has, all you’ve got, all I’ve got.”

Chief Lee defended Cherry in the Brazier and Countryman cases, noting that his “nigger informants” had told him that Countryman had sworn revenge against Cherry for the death of Brazier. Police believed—despite testimony from black acquaintances and relatives to the contrary—that Brazier and Countryman were first cousins since “all the niggers are kin up there.”

Lee blamed all the recent unrest on drinking and outside influence in the wake of the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v Board and the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

“They all got television sets up there and hear all the news over NBC and CBS, telling what the Supreme Court has done and what the Federal Courts say and all about civil rights, and they begin thinking,” Lee told Baker. ‘We’ve had trouble. We’re going to have more of it.”

The article, which was clearly based on a thorough investigation and a nuanced understanding, scooped FBI investigators, who were still waiting on Cherry to return from his vacation. The June 8 front page of The Washington Post reached the desk of W. Wilson White, Assistant Attorney General of the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department, who requested a further investigation into the Brazier trial and pushed legal action. Assistant U.S. Attorney Joseph H. Davis prepared the Countryman, Brazier, Latimer, and Flagg cases to present to a federal grand jury.

The Civil Rights Division had been born just six months previously out of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The infant organization took on the cases in Dawson, which were high profile, by the end of the summer of 1958. From August 4-8, Davis sought indictments against officers Cherry, McDonald, and Edwin Jones for the murders of James Brazier and Willie Countryman, and the injuries of several more black Dawson men. After hearing from more than twenty witnesses, the federal grand jury ruled in line with the kind of southern justice to which Terrell County’s African-American community was accustomed. The jury issued “no bills,” refusing to indict the officers on any of the proposed charges.[26]

Although the case of James Brazier would plod ahead to civil court, Willie Countryman’s legal case would go no further. The official record would maintain that Countryman, not the notoriously violent Cherry, was the aggressor that fatal night.

Edited by Hank Klibanoff