| By Caela Abrams |

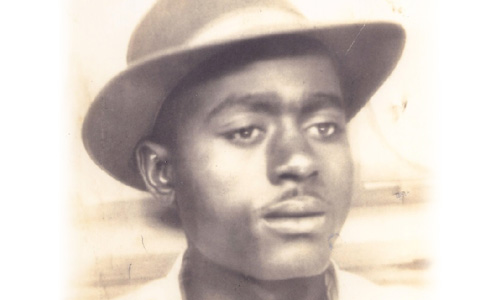

As the Georgia sun set on September 8, 1948, twenty-five year old Sallie Nixon was at home on bed rest. She gave birth to her sixth child just a few days prior. She and her husband, Isaiah Nixon, and their children lived on a sixty-eight acre farm in Montgomery County, Georgia, approximately three hours south of Atlanta. They lived in a large house with a dirt yard and made their living raising livestock and farming tobacco, cotton, and apples. For generations, Isaiah Nixon’s mother, Daisy Davis and her family owned the home and surrounding land.[1]

Sallie Nixon’s daughter, Dorothy Nixon Williams, remembers the good parts of being a young black girl growing up on a Montgomery County farm. She remembers feeling excited about trips to town with her siblings and her father, Isaiah Nixon, via mule-drawn-wagon, and the sweet peppermint candy her father bought. Although Dorothy was only six years old in September of 1948, she still remembers 67 years later that she was gathering vegetables for supper on the eve of September 8 when two white men pulled up to the Nixon property and murdered her father because he voted in the Democratic Primary earlier that day.[2] One week before the election, Klansman Samuel W. Roper asked gubernatorial candidate Herman Talmadge for his thoughts on the best method of keeping black Americans from voting. In response, Talmadge wrote one word on a scrap of paper: pistols.[3]

For about eighteen years, Isaiah Nixon and Dover Carter lived just two and a half miles from each other.[4] Like Nixon, Dover Carter also made his living farming in Montgomery County and in 1946, Carter founded the Montgomery County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP]. Then a forty-one year old father of ten, Carter served as the organization’s president during 1948. Under Carter’s leadership, between 500 and 600 black people registered to vote, including Sallie and Isaiah Nixon, who cast their ballots in the Democratic Primary on the morning of September 8, 1948.[5]

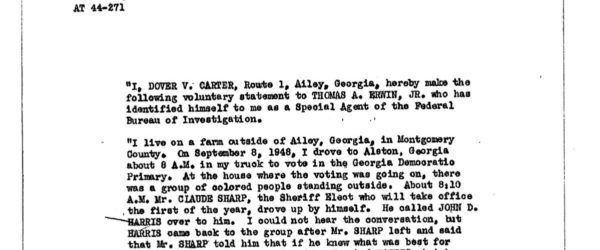

Dover Carter’s orchestration of the Montgomery County NAACP chapter’s voter registration drives made him a target of whites whose efforts to limit the Democratic Party primary only to white voters had failed in the U.S. Supreme Court, twice. After visiting Atlanta in November 1948, NAACP Assistant Special Counsel Franklin H. Williams sent a memo to NAACP national leadership, reporting that Carter had received threats of beatings and death after his initial success in registering black voters in 1946.[6] These threats became reality on the day of the Democratic gubernatorial primary, Sept. 8, 1948, when Carter, at the request of interim Governor Melvin E. Thompson’s local campaign manager, was shuttling black voters to the polls. Two white men, Thomas Jefferson Wilson[7] and Johnnie Johnson[8], blocked Carter’s car and attacked him. As Wilson pointed his shotgun at Carter, Johnson beat Carter until his head was bloody.[9]

Carter would soon flee to Philadelphia. But he had voted that day. So had John D. Harris, a black man who was warned directly by the sheriff elect, W. Claude Sharpe, not to vote that day. So had Sallie and Isaiah Nixon, in defiance of ongoing intimidation.

While campaigning for a fourth term as governor in 1946, the populist and white supremacist Eugene Talmadge had threatened black Americans by saying: “Wise Negroes will stay away from white folk’s ballot boxes.”[10] After analyzing Georgia’s 1946 election, political scientist Joseph L. Bernd determined Gene Talmadge would not have won without the intimidation campaign against black Americans casting their ballots.[11] One victim of this campaign was black World War II veteran Maceo Snipes. He knew the Taylor County KKK had warned against black people voting in the 1946 primary but cast his ballot anyway. Three days later, white men murdered Snipes in front of his home.[12]

One week after Eugene Talmadge’s 1946 victory, white men killed two couples near Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia. In the following weeks, three more lynchings were reported.[13] Journalist Tom O’Connor of P.M. magazine wrote that Talmadge’s victory signaled open season on black Americans and “every pinheaded Georgia cracker and bigoted Ku Kluxer figured he had a hunting license.”[14]

But before Gene Talmadge could take office, he died, throwing Georgia politics into turmoil. The incumbent governor, Ellis Arnall, vowed to stay in office until into his successor could be determined; the lieutenant governor-elect, Melvin E. Thompson, said that with the governor-elect dead, he would become governor the minute he was sworn in as lieutenant governor; and Talmadge’s son Herman claimed to be the rightful heir because Talmadge forces, anticipating Gene might die, had arranged for many people to write in Herman Talmadge’s name on the 1946 ballot. The legislature also went through a process of electing Herman Talmadge governor, a moved the State Supreme Court ruled illegal when it decided Thompson should serve until a new election could be held in 1948 for the final two years of the 1946-1950 term.

Anticipating the 1948 election, KKK Grand Dragon Dr. Samuel Green informed his followers that their mission was to ensure the election of Gene Talmadge’s son, Herman Talmadge, over Thompson as the Democratic Party’s gubernatorial candidate.[15] Herman Talmadge shared Dr. Green’s belief that “God himself segregated the races” and campaigned on a platform of white supremacy.[16]

Under Green’s leadership, the Georgia Klan targeted black advocates of racial change, like Dover Carter, Isaiah Nixon and John Harris, and deterred black voters by sending threatening letters and placing miniature coffins on the porches of black homes.[17] This activity was especially common in the Black Belt,[18] where preventing the black vote by whatever means necessary was critical to maintaining white supremacy.

If black Americans freely took part in the political process across the United States, their voting power would lessen legal, political, economic, educational, and social barriers to freedom and equality. For example, in 1946, black voters in Brunswick, Georgia, publicly endorsed and – amazingly – were able to elect candidates who promised advancements towards equal justice and improved employment by guaranteeing “black jurors and employment for black doctors in the city hospital.”[19] Unfortunately, other black voters were not as successful.

On the evening of September 8, 1948, young Dorothy Nixon and her grandmother Daisy Davis heard a car approach their home and heard two white men calling for her father. Dorothy followed her grandmother toward the front of the house and took a seat next to her younger sister on the steps.[20]

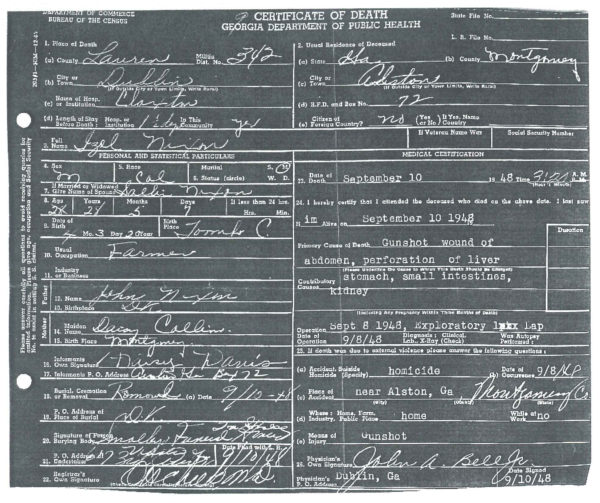

The white men had grown up near the Nixons and were well known to the family: Johnnie Johnson arrived with a shotgun, and his brother, Jim A. Johnson, carried a pistol.[21] Jim A. Johnson called up to the Nixon’s house, demandingIsaiah Nixon come outside.[22] When Nixon stepped onto the porch, Jim A. Johnson asked Nixon how he voted that day. “I guess I voted for Mr. Thompson,” replied Nixon.[23] The Johnson brothers then demanded Isaiah Nixon get into their car. Nixon did not move. Johnnie Johnson aimed his shotgun towards the house. Jim A. Johnson aimed his pistol at Nixon and fired his first shot into Nixon’s stomach.[24] Dorothy – still sitting on the steps – heard her mother come out of the house yelling, “Fall, Isaiah, fall!”[25] Sallie Nixon sprang into action after the Johnson brothers drove off. She carried her husband up the porch steps and into the house; she arranged for a taxi to transport Nixon to Claxton Hospital in Dublin, Laurens County, Georgia. Nixon passed away two days later.[26] His death certificate says he died of gunshot wound of the abdomen and perforations of the liver, stomach, small intestines and kidney.

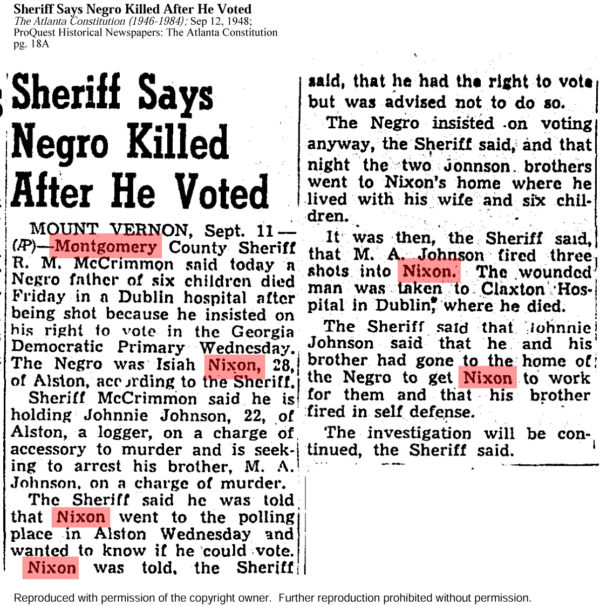

Reports of Nixon’s death traveled quickly. On September 11, 1948, the Atlanta Constitution published an Associated Press report from Mount Vernon, Georgia, containing a statement from Montgomery County Sheriff R. M. McCrimmonIsaiah Nixon insisted on his right to vote after being advised not to do so, and as a result Jim A. Johnson shot Nixon on September 8. Sheriff McCrimmon held Johnnie Johnson on a charge of accessory to murder and announced his intention to arrest Jim A. Johnson on a charge of murder.[27] The Johnsons remained in jail without bond until their trial on November 4, 1948.[28] The Nixon family moved quickly to Jacksonville, Florida, never to live in Georgia again.

Despite countless press releases, newspaper articles, legal aid collection drives, and letters to the Department of Justice, calling for a bona fide prosecution of the Johnsons, there was no justice. The Johnsons, who said they acted in self defense, were not found guilty after a three-hour trial by jury in the Superior Court of Montgomery County. Judge Eschol Graham heard the case but did not recall the presentation of any evidence regarding Nixon having voted when FBI Special Agent Bruce B. Greene interviewed Graham in March of 1949. A transcript of the trial is not available but the court record states Jim A. Johnson was tried first and found not guilty. Then, Judge Graham called a conference of the three prosecuting attorneys during which they “unanimously agreed” that the prosecution had presented their strongest case first and “there was no need to present a case against Johnnie Johnson,” and an order of nolle prosequi was entered for Johnnie Johnson to reflect the prosecution’s decision not to pursue the case.[29]

Daisy Davis told an adolescent Dorothy Nixon that when her father, Isaiah Nixon, cast his ballot, “he stepped over the line.” And for that, Isaiah Nixon lost his life.[30] Sallie Nixon and Daisy Davis doubted the Johnsons were going to be held accountable for killing Isaiah Nixon. Dorothy Nixon Williams recalled Davis asserting that, in 1948, two white men were not going to be convicted of killing a black man.[31]

Read more about the Isaiah Nixon Case

| By Sarah Tiffany | As Isaiah Nixon stared down the barrel of Jim A. Johnson’s gun, his wife yelled, “Fall,

|By Ashley Bianco| In 1948, thirty miles off U.S. Highway One in the small town of Alston, GA, Alexander Rivera, Jr.,

| By Caroline Wilkerson | Sallie Nixon saw it all. She had been at home that morning when Isaiah left to

On September 8, 1948, Dover Carter and Isaiah Nixon, two black men from the small town of Alston, Georgia, went

References

[1] Dorothy Nixon Williams, face-to-face interview with the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class at Emory University, November 4, 2015.

[2] Dorothy Nixon Williams, telephone interview with the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class at Emory University, October 28, 2015.

[3] Chester L. Quarles, The Ku Klux Klan and Related American Racialist and Anti-Semitic Organizations: A History and Analysis. (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1999), 87, citing Stetson Kennedy’s book, The Klan: Unmasked, written in 1954 after he infiltrated the Klan.

[4] NAACP Assistant Special Counsel Franklin H. Williams to NAACP Public Relations Director Mr. Henry Lee Moon, November 26, 1948, NAACP Papers on Dover Carter.

[5] NAACP Assistant Special Counsel Franklin H. Williams to NAACP Public Relations Director Mr. Henry Lee Moon, November 26, 1948, NAACP Papers on Dover Carter.

[6] NAACP Assistant Special Counsel Franklin H. Williams to NAACP Public Relations Director Mr. Henry Lee Moon, November 26, 1948, NAACP Papers on Dover Carter.

[7] The alias “Thomas Wilkes,” used in early FBI files on Isaiah Nixon, has been corrected to Thomas Jefferson Wilson. We know the correct spelling of Thomas Jefferson Wilson’s name from his signed statement given on January 12, 1949, in Mount Vernon, GA to FBI SAC Donald L. Kimble and FBI SAC Bruce B. Greene. The statement is part of the 235 pages of FBI records about the Isaiah Nixon case obtained by the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project through the National Archives and Records Administration.

[8] The alias “Johnny Johnson,” used in early FBI files on Isaiah Nixon, has been corrected to Johnnie Johnson. We know the correct spelling of Johnnie Johnson’s name from his signed statement give on January 12, 1949, in Mount Vernon, GA, to FBI SAC Donald L. Kimble and FBI SAC Bruce B. Greene. FBI records obtained by the cold cases project.

[9] Director, FBI to Assistant Attorney General Alexander M. Campbell, September 14, 1948, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[10] Stephen G. N. Tuck, Beyond Atlanta: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Georgia, 1940-1980. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001), 67.

[11] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 67.

[12] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 71.

[13] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 68.

[14] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 68.

[15] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 17. Stephen Tuck asserts that, by their leadership’s own admission, the Georgia Republican party was ‘dead as a doornail’ in 1937, meaning the Democratic Party’s candidate was destined to win local and state elections.

[16] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 77.

[17] Martin Gitlin, The Ku Klux Klan: A Guide to an American Subculture. (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2009), 24.

[18] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 10. The Black Belt is a region of the Southern U.S., stretching across central and southwest Georgia and formerly home to many large-scale plantations. By 1940, 47 Georgia counties had a majority black population.

[19] Tuck, Beyond Atlanta, 65.

[20] Dorothy Nixon Williams, interview by the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class, November 4, 2015.

[21] Rudolph A. Alt, “Johnnie Johnson; Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” April 4, 1949, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[22] Rudolph A. Alt, “Johnnie Johnson; Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” April 4, 1949, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[23] Director, FBI and SAC, Savannah to FBI, Atlanta, September 11, 1948.

[24] Rudolph A. Alt, “Johnnie Johnson; Jim A. Johnson; Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” April 4, 1949, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[25] Dorothy Nixon Williams, face-to-face interview by Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Class, November 4, 2015.

[26] Isaiah Nixon death certificate, obtained by the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project from Laurens County Health Department. His named is spelled incorrectly as “Izel Nixon.”

[27] AP, “Sheriff Says Negro Killed After He Voted,” Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, GA), Sep. 12, 1948.

[28] Bruce B. Greene, “Johnnie Johnson, Jim A. Johnson, Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” March 28, 1949, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[29] Bruce B. Greene, “Johnnie Johnson, Jim A. Johnson, Isaiah Nixon – Victim,” March 28, 1949, FBI Files on Isaiah Nixon.

[30] Dorothy Nixon Williams, phone interview by Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class, October 28, 2015.

[31] Dorothy Nixon Williams, phone interview by Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class, October 28, 2015.