| Compiled from student research and reports |

James C. Brazier, a husband and father, a 31-year-old striver who worked two and sometimes three jobs, spent most of his Sunday, April 20, 1958, as he usually did: with his extended family, in church, in Terrell County in rural southwest Georgia. The Brazier family started the day at I Hope Baptist Church in Dawson, then drove 20 miles past cotton and peanut fields to Mt. Mary Baptist Church in Sasser.

A 1958 blue Chevy Impala similar to the one James Brazier drove, photo courtesy Chad Horwedel

Late that afternoon, when the day-long services ended, James Brazier got behind the wheel of the 1958 blue and white Impala he had bought at the Chevrolet dealership where he worked, and shuttled family members to their homes. His father, Odell Brazier, got into the 1956 Chevrolet that James Brazier had purchased a couple of years earlier and did the same.[1]

After dropping off family members at their homes, James Brazier was driving through Dawson on his way home to his wife and four children when he saw a sight that was both familiar and dreaded in the Jim Crow South: A white police officer roughing up a black motorist. James Brazier had a special reason to fear that scene. Dawson Police officers, all of them white, had arrested Brazier, an African-American, seven times in the previous four years. They had charged him with speeding, contempt, disorderly conduct, drunk and disorderly conduct, and DUI and speeding. Most of the fines had run $10 to $15.[2]

Trapped in the Web of a Ruthless Routine

As Emory student papers show in the stories on this website, the police targeting of James Brazier had accelerated in recent months – and the raw rationale for the police behavior had begun to reveal itself. In November 1957, when James Brazier was driving his new 1958 Chevrolet Impala, Dawson Police Officer Weyman Burchle Cherry had stopped him, charged him with DUI and speeding, and arrested him. When Cherry took him to jail, Brazier would later tell his wife, the officer hit him so hard in the back of the head that Brazier fell to the ground. “You smart son-of-a-bitch,” Brazier recalled Cherry saying, “I’ve been wanting to get my hands on you for a long time.”

“Why you want me for?” Brazier responded.

“You is a nigger who is buying new cars and we can’t hardly live,” Cherry explained. “I’ll get you yet.” He hit Brazier again, then stomped him in the back so hard, Hattie Brazier would later say, that she could see Cherry’s shoeprint on her husband’s back when he was returned home, vomiting and with blood coming out of his ear.[3]

That flare-up of racial resentment had occurred only five months before the Sunday in April when James Brazier saw that Dawson Police Officer Randolph Ennis McDonald had pulled a black motorist to the side of the road. As Brazier drew closer, he could see the motorist was his father, Odell Brazier. The elder Brazier and McDonald were engaged in an argument. McDonald had said Odell Brazier was weaving in his car and had been drinking; Odell Brazier had insisted he had been in church all day, had not been drinking, and was driving safely. McDonald, with another white man who arrived on the scene, were trying to push Odell Brazier into the police car. When the elder Brazier resisted, McDonald pulled out a slapjack and, Odell Brazier would later say (and his damaged eye would seem to corroborate), hit him across his eyes and the bridge of his nose. James Brazier, seeing his father’s struggle, got out of his car and walked quickly toward McDonald and his father. “Don’t hit my daddy,” he said to McDonald, then offered to help get his father in the patrol car.[4]

At that moment, James Brazier’s tragic fate was decided. As the Emory student papers that follow show, James Brazier, by driving up to the scene in a new automobile that upended and offended white supremacists’ insistence on economic advantage, then by uttering an imperative to Dawson police officers (“Don’t hit my daddy”), even while offering to help, had become snared in the maddening, inescapable web of the Jim Crow South. The Emory students’ research revealed that James Brazier, working three jobs, in fact did make more money than the police officers. But the numbers would not have mattered; the students, who examined the role of automobiles in race relations as well as the state of black consumerism in the last 1950s, found that James Brazier’s display of middle-class comfort was sufficient.

The Dawson confrontation in Spring 1958 came amid rising tensions in the South — four years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared school segregation unconstitutional in the Brown v. Board decision of 1954, less than three years after Emmett Till was killed in the Mississippi Delta, a little more than a year after the 381-day Montgomery bus boycott ended, and seven months after the showdown in Little Rock over the integration of Central High.

The Message from the Top: Resist at All Costs

Georgia’s political leadership in 1958 was not merely passively segregationist. Gov. Marvin Griffin, Attorney General Eugene Cook, and former House Speaker Roy V. Harris were in the South’s vanguard of white supremacist politicians who added muscle, vitriol and open encouragement to the massive resistance movement spreading over the South. Their influence went beyond Georgia’s borders. In the fall of 1957, days before Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus was to fulfill his longstanding promises to steer Little Rock peacefully and safely toward school integration, Gov. Griffin and Roy Harris showed up at the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion. They had a message for Faubus: If he allowed black students into Central High School, he would go down in history as a traitor to his white race and certainly would not be reelected in Arkansas. Faubus, viewed as a racial moderate, stunned his state by buckling under to last minute pressure and calling out the National Guard to stop nine black students from enrolling at Central High. [5]

- Eugene Cook in an interview with Atlanta Journal reporter Davenport Stewart, Atlanta, GA, 1947, copyright Atlanta Journal-Constitution, courtesy Georgia State University.

- Marvin Griffin with Lester Maddox and George C. Wallace, February 14, 1968, Charles Bennet photographer, copyright Atlanta Journal-Constitution, courtesy Georgia State University.

- Roy Harris (left) with Roy Rivers, June 1951, Frank Tuggle photographer, copyright Atlanta Journal Constitution, courtesy Georgia State University.

Under Griffin, Cook and Harris, white supremacists in Georgia, including those in law enforcement, felt they had sanction to push hard and violently to stop racial integration. In 1955, Attorney General Cook, who would later serve on the Georgia Supreme Court, gave a speech to Georgia law enforcement officers calling the NAACP communist-led and “un-American.” He announced his plan to “totally disrobe the NAACP and to present this sinister and subtle organization in all its nakedness.” Roy Harris would later praise whites who rioted in a failed attempt to stop the desegregation of the University of Georgia in 1961.[6]

The impact of that invective from political leaders resonated across the state. In the everyday relationships between white police officers and black residents of far-flung towns across Georgia, few of the messages coming from the political leaders counseled restraint in the use of force to maintain white supremacy and black subservience.

James Brazier, who had no involvement in civil rights activity, was about to receive that message in the most brutal way.

“They may be coming after me”

At the Terrell County Jail, Officer McDonald put Odell Brazier in jail then rounded up Officer Cherry to join him in paying a visit to James Brazier’s home. A few minutes later, Hattie Brazier saw the police car racing down North Ash Street, where she, James, their two daughters and two sons lived.

“Where they going in such a hurry now?” she asked.

“They may be coming to tell me daddy need the doctor…” James Brazier responded. “Then again, they may be coming after me.”

“Coming after you for what?” Hattie Brazier said. She added, in half-statement, half-question: “You ain’t did anything?”

“No, but you know how they is around here,” James Brazier said. “The only thing I said was ask them not to hit him, but to put him in jail if he did anything wrong.”[7]

Officer Cherry and McDonald arrived without displaying a warrant, and met James Brazier in his front yard.

“James, what did you say you were going to do to me?” Officer McDonald said as he walked toward James Brazier, Hattie Brazier later recalled.

“I didn’t say I was going to do anything to you,” James Brazier replied.[8]

As neighbors watched, the officers said they had come to arrest him for interfering with a police officer. They grabbed him and tried to force him into a police car. Brazier insisted that he had done nothing wrong. As the tension escalated quickly, Brazier’s wife Hattie urged him to comply. James Brazier’s ten-year-old son James Jr. tried to intervene – just as the elder James Brazier had done when his father Odell was being arrested about an hour earlier. Police swatted the young boy away, then started pummeling James Brazier. Cherry slammed James Brazier in the forehead, pulled his pistol and stuck it into Brazier’s chest, Hattie Brazier would later say.

“I ought to blow your Goddamn brains out, you smart son-of-a-bitch,” she recalled Cherry saying.

“Well, shoot me if you want to, I ain’t done nothing for you all to treat me like this,” Brazier responded.[9]

Some witnesses, including Hattie Brazier and James Brazier Jr., said Cherry pistol-whipped Brazier. Cherry would later acknowledge he pulled his pistol on Brazier and that he hit Brazier, but said he did not hit Brazier with the pistol.[10]

The Protective Cover of a Medical Misdiagnosis

While neighbors who watched the arrest portrayed Cherry and McDonald as unrelenting in their attack on Brazier, the officers would say they were not especially rough with him. Yet they were sufficiently worried about his condition when they arrived at the Terrell County Jail that they called a physician to examine him. Dr. Charles M. Ward, a graduate of the Medical College of Georgia and a former flight surgeon for the U.S. Navy, examined Brazier in jail that night. There were no black physicians in Dawson and few in Georgia, especially rural Georgia. Ward, a white physician, a member of the Dawson city commission and employed by the county hospital to examine inmates, saw blood in Brazier’s ear and nose and observed his slurred speech. Ward would later acknowledge that he did not ask Brazier how he came to be injured. “I never ask such questions. I had rather not know,” Ward said.[11]

Neglecting the obvious signs of a fractured skull and possible brain damage, Ward concluded that Brazier was simply drunk. Instead of sending him to the hospital and ordering x-rays, Ward covered a couple of lacerations with a bandage and told officers to check on Brazier every couple of hours. As two student essays that follow reveal, that critical misdiagnosis was the first of several indications that the medical response to Brazier’s injuries would range from indifference to neglectful to cruel.[12]

Cherry and McDonald put James Brazier in a cell on the women’s side of the jail, still dressed in his Sunday suit. But they were not done with him. During the middle of the night — under the watchful eyes of at least three other inmates who, at great risk, would later describe what they saw — the officers returned and went to Brazier’s cell. As the officers grabbed him and put a blindfold on him, Brazier begged the policemen to leave him alone as he struggled to stay in his cell. In a grasp for dignity, he asked the officers if he could put on his shoes. “You won’t need no shoes,” one of his abductors responded ominously.[13]

James Brazier was gone two, maybe three hours. Then, in the darkness of the morning, as inmates watched from their cells, Cherry, McDonald, two other police officers and a deputy sheriff returned to the jail, carrying Brazier wrapped in a U.S. Army blanket. He was stripped of his Sunday clothes and was a bloody, near-lifeless mess. He groaned in pain as he lay on a mattress that absorbed his blood.[14]

There to greet the officers was Terrell County Sheriff Zachary Taylor (“Zeke”) Mathews. “How did you come out?” Mathews asked the officers, the inmates would later recall. “Did you do a good job?” [15] He then dispatched an inmate, Eugene Magwood, who held the special status of “trusty,” to take the sheriff’s truck and fetch Brazier’s clothing. As three students explore in an accompanying essay, Magwood, as the sheriff’s designated trusty inside the jail, operated in a murky world that was well known in southern jails, a world where a trusty’s snitching and betrayal of other inmates brought him freedom beyond the jail, hunting trips with the sheriff, and access to the women’s cells.

Shocked, Hattie Brazier Takes Charge

The next morning, unable to walk or speak coherently, Brazier was carried into Mayor’s Court to enter a plea to the charge. When the mayor, acting as a judge, saw Brazier’s condition, he postponed the case. Hattie Brazier entered the courtroom and was shocked to see her husband slumped over, drooling and incoherent. Dawson Police Chief Howard Lee, whose department shared custody of James Brazier with the sheriff’s office for the prior 15 hours, dismissed the obvious signs that James Brazier needed urgent medical attention and told Hattie Brazier to take her husband home and bring him back for his court date three days later.

Instead, Hattie Brazier took charge. She piled her husband and family into their car and raced to Terrell County Hospital in Dawson, where she encountered stunning callousness by a local physician.[16] At the front of the hospital, as James Brazier lay across the back seat of his car in and out of consciousness, his head resting on his sister’s lap, Mrs. Brazier spotted a white physician standing outside. His name was Dr. Walter Martin and he shared a practice with the physician who had examined Brazier in jail, Dr. Charles Ward. She begged Martin to come look at her husband. Martin, she said later, peered into the car window and said, “Ain’t nothing ailing him, nigger… There ain’t nothing ail the damn nigger but drunk.”[17]

Hattie Brazier, frantically trying to get medical attention for her husband, managed to get him inside the hospital, where she saw that Police Chief Lee had arrived and was speaking with Dr. Ward privately in a small room. As they continued talking, she grew impatient with their seeming indifference. She interrupted them and told Ward she was leaving and taking her husband. “He needs working on,” she told Ward. “I’m going to take him out and take him to another doctor.”

“No, wait,” Ward said. “I’m going to look after him.” He quickly got Brazier into an x-ray room. When Ward emerged, his explanation stunned and stung Hattie Brazier: “It ain’t nothing I can do for him, widow.”[18] He had written off her husband, declared him dead, when he was still alive.

Hattie Brazier rushed her husband to Columbus, Georgia, 60 miles away, where he was admitted to the Columbus Medical Center. As James Brazier awaited medical care, his father Odell Brazier quickly pleaded guilty to reckless driving and driving under the influence, then headed to Atlanta, where he met with FBI agents to tell of the terror in Terrell County. As you will read in an essay by two students that follows, FBI agents descended on Terrell and begin an investigation that was never quite full-tilt – it was encouraged by the Department of Justice’s new Civil Rights Division but not embraced in the FBI’s headquarters. What’s more, agents encountered unique Georgia laws that limited federal investigations into local law enforcement wrongdoing.

The FBI presence did nothing to quell what happened next in Dawson and Terrell County. Over the next month, police Officer Cherry shot a black electrician in the buttocks, then shot and killed a black, 32-year old driver for a soda company, Willie Countryman. When a 21-year old black man who was playing ball outside saw a police car and held his arms up as if holding an imaginary gun, Dawson Police arrested him; when the young man’s mother came to bail him out, she was thrown behind bars. Two officers, including McDonald, were involved in beating another black man.

On April 25, five gruesome and painful days after his Sunday afternoon drive through Dawson, James Brazier died. On the day of James Brazier’s funeral at I Hope Baptist Church, Dawson Police inflicted one more insult on the Brazier family. As Odell Brazier was driving through town, he saw a Dawson Police car following him. He drove with special care to avoid giving them any reason to stop him. It didn’t matter. They arrested him, claiming he had run a stop sign.[19]

Where the Minority Rules and the Fight is Over Scraps

As in much of the South, Terrell County was majority black and minority-ruled in the late 1950s, and beyond. Blacks represented 64 percent of the county’s 12,700 population in 1958, but only about 100 blacks were registered to vote. The county’s economy was dependent on peanut and cotton crops and its people were poor. The median annual income in the U.S. was $5,600; in Terrell County, the median was less than half that, $2,057. But it was the impoverishment of blacks that weighed down that countywide number: White families in Terrell County had a median annual income of $4,300; black income was less than a third of that, $1,300. As student research makes clear, Officers Cherry and McDonald made substantially less than the median for whites in the county, and James Brazier made considerably more than the median for blacks.

The median level of education among Terrell County whites over 25 years old was 10th grade in 1958; for black residents, the median fell between 4th and 5th grades.

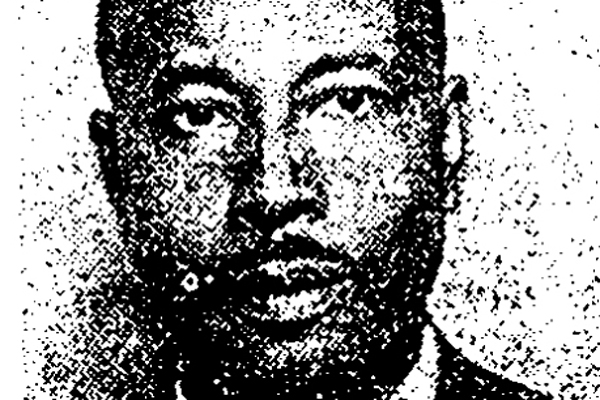

Terrell County and its county seat, Dawson, would produce three people who achieved great recognition. One was Benjamin J. Davis Jr., born in 1903, a Harvard Law graduate, and a member of the city council of New York City. His open embrace of communism cost him some jail time. Davis’ political awakening came in the mid-1930s when he defended a young black Georgia man, Angelo Herndon, who had been convicted in state court of “attempting to incite insurrection” by organizing a union. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually struck down Georgia’s insurrection law as unconstitutional.

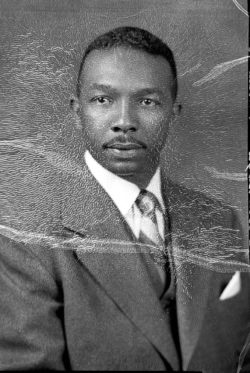

Walter Washington while a student at the Howard University Law School, Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

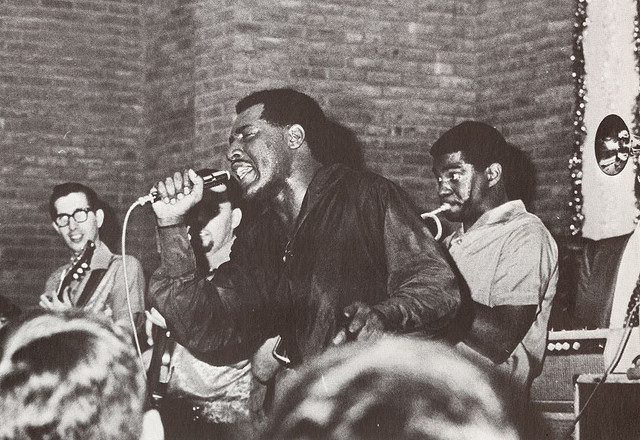

A second notable from Dawson was Walter Washington, born in 1915, who went on to become the first black mayor of Washington, D.C.; and a third was Otis Redding, born in 1941. Redding’s voice and his presence on stage carried rhythm and blues into the soul era and became one of the first black artists to appeal to the post-World War II generation of young whites, even in the South.

Otis Redding sings at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County CREDIT

All three men were African-American; none of them is recognized in Dawson or Terrell County by signage, historic markers, or even passing mentions on the city’s or county’s websites.

One Dawson resident who did not leave was James Calvin Brazier, known to many as Bubba. James Brazier, born in 1926, had served in the U.S. military during World War II, had been honorably discharged, and had returned to Dawson. He held two jobs through the company that owned the Chevrolet dealership in town, often a third job, and his wife Hattie worked two jobs. James Brazier had a special and unapologetic love for cars.

A reign of unrestrained, unreported police attacks

James Brazier’s death went unreported in the local mainstream weekly newspaper, The Dawson News. So did the death of Willie Countryman, shot in his own backyard by Officer Cherry a month later. So did Officer Cherry’s shooting of Tobe Latimer; and his assault, with Officer Edwin Harold Jones, on Billy Flagg, whose mother was arrested when she showed up at the jail to check on her son and became emotional when she saw him. Officer McDonald, whose arrest of Odell Brazier precipitated the events that led to James Brazier’s death, joined Officer Jones in an attack on Eugene Renfroe, also unreported in the newspaper. The NAACP knew of others: Sammy Minton, Peyton Jordan, R.C. Amos, “Brother” Martin, and Frank Burks (“so brutally beaten pieces of his skin were torn off,” the NAACP determined). A Dawson police chief was identified by the NAACP as the man who in the 1940s had handcuffed a black man on a main street in downtown Dawson, then shot and killed him. All the officers were white and all the victims were black.[20]As a student’s profile of Officer Cherry suggests, there was a reward, not a penalty, awaiting officers who brutalized blacks.

The Dawson News saw no story in the rash of killings and beatings, others would. The FBI had begun scratching at the case andrunning into fear and distrust from the jailhouse eyewitnesses when the NAACP’s new field secretary, Amos Holmes, headed to Terrell County to join Hattie Brazier in investigating. As a student essay on Holmes shows, witnesses reluctant to speak with the FBI talked with Holmes. He reported his findings to the NAACP regional leader Ruby Hurley in Atlanta, who shared them with a few influential civil rights organizations, including the Southern Regional Council (SRC) in Atlanta, which was entering its fourth decade pursuing racial justice in the South. Harold Fleming, the executive director of the SRC, passed the findings along to Alfred Friendly, managing editor of The Washington Post, who assigned reporter Robert E. Lee Baker to the story.[21]

Terrell County’s debut on the national stage

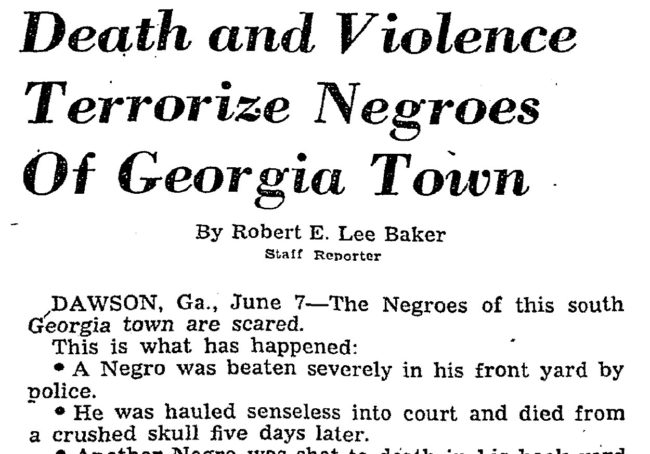

Baker spent some time in Dawson, then holed up in Albany to hear the frightening accounts from blacks who sneaked over from Dawson to tell their stories. Baker’s front-page story on June 6, 1958 — it carried the dateline of Dawson and the headline “Death and Violence Terrorize Negroes in Georgia Town” – described in detail, brutal case by brutal case, a police reign of terror, and a smug indifference to what the outside world thought.

The Washington Post picked up the Brazier story and published an article with this pointed headline. The Washington Post and Times Herald, June 8, 1958.

The story introduced Terrell County’s longtime sheriff, Zachary Taylor (Zeke) Mathews, to the national stage in a role he seemed to relish. “You know, Cap’,” Mathews said to Baker and, by extension, the political establishment in Washington, “there’s nothing like fear to keep niggers in line. I’m talking about ‘outlaw’ niggers. And we always tells them there are four roads leading out of Dawson in all directions and they are free to go anytime they don’t like it here.”

Chief Lee spoke with equal disdain. When discussing a black man whom police had shot in the buttocks, Lee said to the reporter, “All the niggers around town were laughing about where old Tobe got shot.” When discussing Officer Cherry’s shooting of Willie Countryman a month after Brazier, Lee said, “I remarked on the way to the hospital how quick he seemed he died. I had to shoot one in the stomach a few years ago and he lived five or six days.” Lee and Mathews felt protected enough to provoke Washington by telling the FBI to stay out. “Coming down here all the time is a waste of taxpayers’ money,” Lee said. Mathews added: “It aggravates me worse because the FBI starts talking to niggers and then niggers get to thinking they’re important and it stirs them up.”

The law officers made no pretenses about the threat they felt. “Well, Cap’, I believe we ought to be strict about who votes,” Mathews said. “There isn’t a nigger in Georgia who wouldn’t take over if he could. They want all the power.”

Neither Mathews nor Lee showed the slightest concern about appearing on the front pages of The Washington Post as parodies – indeed, Mathews would reappear in the same role on the front page of The New York Times four years later. They may have been preening for the press, but they were serious. And the new Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, catalyzed by the Post article, took them seriously.[22]

The Civil Rights Division had been created only the previous September upon passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act. In response to the Post article, the division’s first director, assistant attorney general W. Wilson White, began sending off memos trying to find out what the FBI was doing in Terrell County. The relationships between the new division, the FBI offices in Georgia and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover were unclear and conflicting. FBI agents in Georgia, who had slowed down their probe while awaiting further orders from Hoover, picked up their investigation.[23]

But local and state law enforcement showed no interest in pursuing any of the police brutality cases in Terrell County. In that void, the Civil Rights Division and the FBI worked hastily to present evidence against Dawson police officers to a federal grand jury. That grand jury met for four days in Macon in August 1958 but declined to bring any charges against the law enforcement officers.[24]

The mysterious fates of eyewitnesses

Grand jury proceedings are secret and information about this grand jury has not been found, so it is not known what witnesses were called. But it is known, as a student essay reveals, that Officer Cherry made sure that Marvin Goshay, who shared a cell with James Brazier at one point during Brazier’s last night, could not testify to the grand jury. Shortly before Goshay was scheduled to testify, Officer Cherry arrested him and kept him in jail until the grand jury completed its work on the Brazier case. When Goshay asked why he was being detained, the officer responded, “You just need to be in jail.”[25] Goshay, as a student explains, would face an even more mysterious and perhaps suspicious outcome.

The fates of the remaining two eyewitnesses – Irene Gladden and Mary Carolyn Clyde — were equally disturbing, Emory students have discovered and described in essays.

After the grand jury declined to bring criminal charges, the same law enforcement officers who had harassed Hattie Brazier’s husband turned their hostility on her.

In 1959, even after she had fled to neighboring Dougherty County, Dawson policemen arrested her in Albany on a charge of stealing her own “power mow” from her father-in-law (Odell Brazier), who had borrowed it.[26]

That same year, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission would later report, Sheriff Mathews encountered Hattie Brazier and his enmity spilled out. “A nigger like you, I feel like slapping them out,” he told her, commission investigators concluded. “You niggers set around here and look at television and go up North and come back and do to white folks here like the niggers up North do, but you ain’t gonna do it. I’m gonna carry the South’s orders out like they oughta be done,” the sheriff continued.[27]

Hattie Brazier was threatened but not intimidated. She decided to file a civil lawsuit in federal court and seek damages against Dawson Police Officers Cherry, McDonald and Sirah Chapman, Police Chief Howard Lee, and Sheriff Mathews. She would finally get her three days in court in a federal courtroom in Americus in February 1963, nearly five years after her husband was killed.[28]

Terrell County would solidify its reputation as one of the most dangerous, violent settings in the South for blacks, making “Terrible Terrell County” the reflexive depiction of the county among black residents and civil rights workers. In July 1962, reporters from The New York Times,The Atlanta Constitution and The Atlanta Journal went to Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Sasser, Terrell County, to write about workers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) seeking to persuade older blacks to register to vote.

As SNCC leaders Charles Sherrod and Ralph Allen began speaking, congregants inside the church could hear muffled sounds coming from the gravel parking lot – the sound of men calling out the license plate numbers of the people inside. Soon the church doors swung open and in walked Sheriff Mathews, in full bloom, with deputies, a sheriff from another county in tow, and assorted white men–13 in all.

Sheriff Mathews makes the front page—again

Mathews made his way to the front of the church and turned to face the 38 potential voting registrants sitting in the pews and two white Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers. Mathews, whose uninhibited racism had been on full display in The Washington Post’s front-page story about Dawson in 1958, was about to land, unreformed and unrepentant, on the front page of The New York Times. As Mathews began to speak, Claude Sitton, the southern correspondent for The New York Times, began to take notes. Two days later, in a story datelined Sasser, Georgia, July 26, 1958, readers of the front page of the Times caught the intimidating flavor of the evening from the opening paragraph of Sitton’s story:

“‘We want our colored people to go on living like they have for a hundred years,’” said Sheriff Z.T. Mathews of Terrell County. Then he turned and glanced disapprovingly at the 38 Negroes and two whites gathered in the Mount Olive Baptist Church here last night for a voter-registration rally. ‘I tell you cap’n, we’re a little fed up with this registration business.’”

Sitton reported that as Mathews spoke, “his nephew and chief deputy, M.E. Mathews, swaggered back and forth fingering a hand-tooled black leather cartridge belt and a .38 revolver. Another deputy, R.M. Dunaway, slapped a five-cell flashlight against his left palm again and again. The three officers took turns badgering the participants and warning of what ‘disturbed white citizens’ might do if this and other rallies continued.”

Sitton then described a verbal battle for control of the room as Sherrod led the audience in prayers and hymns while Mathews and his men sought to intimidate and belittle. Mathews said he didn’t think blacks were “dissatisfied with life in the county,” then asked everyone from Terrell County to stand up.

“Are any of you disturbed?” the sheriff asked as Sitton scribbled in his notebook. The response, Sitton reported, “was a muffled ‘Yes.’”

“Can you vote if you are qualified?” Mathews asked. “No,” said the audience.

“Do you need people to come down and tell you what to do?” “Yes,” came the response.

Mathews was not getting the answers he wanted. He tried one more: “Haven’t you been getting along well for a hundred years.” The response: “No.”

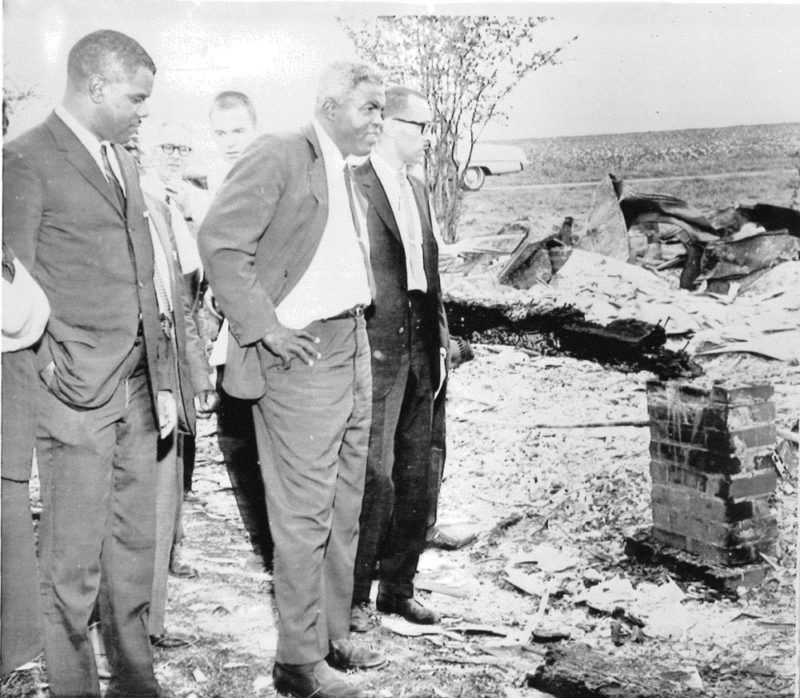

Jackie Robinson at the scene of Mt. Mary Baptist Church in Sasser, Terrell County, Georgia. Photo courtesy the Associated Press NEEDED

The day the story appeared in The New York Times, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was so upset by the article that he ordered the head of the Civil Rights Division, Burke Marshall, to head immediately for Terrell County and to renew intimidation and harassment charges the Justice Department had brought against the sheriff after The Washington Post story in 1958.

Two months later, in September 1962, white supremacists burned down that church, Mt. Olive, as well as another black church, Mt. Mary, which the Brazier family had attended the day he went to jail. The church-burnings drew national attention and protest and attracted major league baseball pioneer Jackie Robinson, born 75 miles south in Cairo, Georgia, who walked amid the sacred ashes.

Last chance for justice

The case, Hattie Brazier v. W.B. Cherry, Randolph McDonald, Zachary T. Matthews (sic), et al., had a cast of characters that suggested a titanic constitutional battle was underway. Hattie Brazier, whose determination to vindicate her husband is evident in a student profile, arranged for the two most prominent African-American lawyers in Georgia to take her case – Donald Hollowell of Atlanta (examined in a student profile) and C.B. King of Albany, who at the same time were representing Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes in their historic and ultimately successful effort to break the color line at the University of Georgia in 1961. In a state that historically had not been home to many blacks with legal education, they were leaders of a new generation of black attorneys in Georgia who were less accommodationist, more confrontational and more willing to use the law to advance civil rights.

They were up against heavy artillery: Cherry, McDonald and Mathews were defended by Charles Bloch of Macon and James M. Collier, who was mayor of Dawson at the time. Both, in introducing themselves to the all-white jury, invoked the names of their close friends, the leading political figures of the region and the state, and wrapped themselves, and the jurors, in the protective cloak of white familiarity — something Holloway and King could not do. Bloch’s legal acumen and white supremacist views made him a popular speaker for states’ rights among massive resisters in Georgia and Washington. He stood alongside political giants: At the acrimonious 1948 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, when the party was sundered on the left by former vice president Henry Wallace’s liberal breakaway group and on the right by segregationist Southern delegates weighing defection to the Dixiecrats, it was Bloch to whom southern delegates turned in a last ditch effort to keep the party together: He was chosen to deliver the convention hall stemwinder they hoped would lead to the nomination of U.S. Sen. Richard B. Russell of Georgia as an alternative to President Harry Truman as the party nominee. Nominate Russell, Bloch told the sweltering crowd, and “You shall not be crucified on the cross of civil rights.”[29] From 1956, when he served as an attorney for the state in seeking to preserve segregated school systems (in defiance of the Brown decision), Bloch was all but on retainer from Georgia’s white supremacist governors. Marvin Griffin sent him to deliver testimony to Congress against the 1957 civil rights legislation, as did Ernest Vandiver when fresh civil rights laws were proposed.[30] Bloch’s Jewish religion made him an anomaly in a civil rights movement where many Jews and blacks felt common cause in shared histories of oppression. Bloch apparently had not been especially moved by the burning of black churches and dismissed suggestions that the seed of racism in white supremacist organizations bore anti-Semitic attitudes as well. Bloch had no difficulty reconciling his points of view as a Jew and a white supremacist until it became clear in the early 1960s, despite his initial denials, that renegades who had been bombing and burning synagogues in the South for two years came from the same political and ideological corner as those who were burning black churches.[31]

They were up against heavy artillery: Cherry, McDonald and Mathews were defended by Charles Bloch of Macon and James M. Collier, who was mayor of Dawson at the time. Both, in introducing themselves to the all-white jury, invoked the names of their close friends, the leading political figures of the region and the state, and wrapped themselves, and the jurors, in the protective cloak of white familiarity — something Holloway and King could not do. Bloch’s legal acumen and white supremacist views made him a popular speaker for states’ rights among massive resisters in Georgia and Washington. He stood alongside political giants: At the acrimonious 1948 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, when the party was sundered on the left by former vice president Henry Wallace’s liberal breakaway group and on the right by segregationist Southern delegates weighing defection to the Dixiecrats, it was Bloch to whom southern delegates turned in a last ditch effort to keep the party together: He was chosen to deliver the convention hall stemwinder they hoped would lead to the nomination of U.S. Sen. Richard B. Russell of Georgia as an alternative to President Harry Truman as the party nominee. Nominate Russell, Bloch told the sweltering crowd, and “You shall not be crucified on the cross of civil rights.”[29] From 1956, when he served as an attorney for the state in seeking to preserve segregated school systems (in defiance of the Brown decision), Bloch was all but on retainer from Georgia’s white supremacist governors. Marvin Griffin sent him to deliver testimony to Congress against the 1957 civil rights legislation, as did Ernest Vandiver when fresh civil rights laws were proposed.[30] Bloch’s Jewish religion made him an anomaly in a civil rights movement where many Jews and blacks felt common cause in shared histories of oppression. Bloch apparently had not been especially moved by the burning of black churches and dismissed suggestions that the seed of racism in white supremacist organizations bore anti-Semitic attitudes as well. Bloch had no difficulty reconciling his points of view as a Jew and a white supremacist until it became clear in the early 1960s, despite his initial denials, that renegades who had been bombing and burning synagogues in the South for two years came from the same political and ideological corner as those who were burning black churches.[31]

Charles Bloch, the Macon, GA defense attorney in Hattie Brazier v. W.B. Cherry, Randolph McDonald, and Zachary T. Matthews, et al., ???

The judge in the case was himself a known quantity in Georgia politics. As shown in a student essay that follows, U.S. District Court Judge J. Robert Elliott had been a staunch segregationist when he was part of the Herman Talmadge machine in the Georgia legislature and a Democratic National Committeeman. One of his first decisions as a federal judge had been to deny Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s request for a permit to hold a march in Albany.[32]

Hattie Brazier had one slim chance of prevailing in Judge Elliott’s court before an all-white, all-male jury. Of the three eyewitnesses, two had died. As a student essay indicates, very little can be found about Irene Gladden, other than a record of her death on Ancestry.com that shows she died after Holloway interviewed her but three months before depositions were taken and six months before the trial began. Marvin Goshay, as a student writes, died in 1961, “apparently” of asphyxiation in a Dawson undertaker’s parlor under circumstances the FBI found suspicious enough to investigate, to no avail.[33]

“I couldn’t tell the truth”

The witness who had provided to the NAACP and, ultimately, the FBI the most incriminating eyewitness description of what occurred in the jail the night Brazier was beaten was also the shakiest. Mary Carolyn Clyde, only 19 when she was jailed on manslaughter for killing her husband, had been afraid to share the truth with FBI agents when, inexplicably, they first interviewed her inside the sheriff’s office. During the interview, the sheriff entered his office and interrupted the interview frequently and his trusty listened through an open window. Through an intermediary, Clyde later told the NAACP’s Amos Holmes the truth, shared more with the FBI, and revealed to Hollowell an account he believed any jury would find compelling.

But Hollowell, a student essay explains, did not know if he could rely on Clyde to tell the truth in court. Both Holmes and Hollowell had heard that police had threatened and bribed Clyde, and they believed she was being abused in the jail. On the day Mary Carolyn Clyde took the witness stand in federal court in Americus, she sat only feet from the men accused of killing James Brazier: Officers Cherry and McDonald, and Sheriff Mathews. She signaled quickly that her fears overshadowed her comfort with the truth. Under oath and on the cusp of bringing a measure of justice to the long harassment and then death of James Brazier, Mary Carolyn Clyde, fidgeting with her hands and stumbling in her responses, contradicted her previous statements. She denied seeing anything unusual in the jail the night Brazier was brought in, removed from his cell, and returned all but dead.

After three full days of testimony that ended on Feb. 8, 1963, the judge gave the jurors instructions, sent them to deliberate, quickly brought them back to clarify an instruction, then sent the jurors to deliberate at 4:50 p.m. At 6:10 p.m. – an hour and twenty minutes later – the jury informed the court it had reached a decision. In a few short words, Hattie Brazier’s hopes to avenge her husband’s murder were dashed. The foreman rose and declared, “We the jury find for the defendants.”

In August 2013, three members of the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory — Professors Hank Klibanoff and Brett Gadsden and then-student Mary Claire Kelly — located Mary Carolyn Clyde and met with her in her home. She was confined to a wheelchair. She remembered the James Brazier story, the federal case, the abusive trusty and her own reluctance to tell the truth when it mattered most. Why had she not told the truth at the trial? She did not have to remind her interviewers that the police officers and sheriff had intimidated her during her FBI interview, arranged for the trusty to eavesdrop on her, spied on her and, her friends told the NAACP and Hollowell, bribed her. As she sat on the witness stand, she told the Emory interviewers, she was only a few feet from the sheriff and the two police officers accused of killing James Brazier.”I couldn’t tell the truth,” she said, “when they were there.”

Today, the James Brazier case is little known and long forgotten, except by his family. He is buried in Sardis Cemetery with his wife Hattie Bell Brazier, his father Odell Brazier and other family members. But finding his grave site without the help of his family is impossible. Time and the elements have rubbed away the words on his headstone – his identity as James Calvin Brazier – and made his name unreadable. He has become the invisible man.

James Brazier’s weatherworn headstone, photo courtesy Mary Claire Kelly

Edited by Hank Klibanoff

References

Bush, Verda Brazier, Sara Brazier and Hattie Brazier Polite. Interview by Brett Gadsden, Hank Klibanoff and Mary Claire Kelly. Personal Interview. Dawson, Georgia, August 16, 2013..

Testimony of Randolph McDonald, Hattie Brazier v. W. B. Cherry, Randolph McDonald, Zachary T. Matthews [sic], et al., C.A. 475, M.D. Ga. (hereafter cited as Brazier v. Cherry), February 8, 1963, The National Archives at Atlanta;

Deposition of Odell Brazier, Brazier v. Cherry, November 24, 1962;

Testimony of Odell Brazier, Brazier v. Cherry.

“Roy V. Harris”, New Georgia Encyclopedia, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/roy-v-harris-1895-1985

Affidavit of James Brazier Jr., June 12, 1958, NAACP files, Manuscripts Collection, Library of Congress, on microfilm at Woodruff Library, Emory University.

As he continued to cover civil rights in the South for The Washington Post, Robert E. Lee Baker changed his byline to Robert E. Baker.

FBI, WILLIE COUNTRYMAN, Bureau File 44-13236.

The tensions between the Civil Rights Division and the FBI are evident in various memos in the Countryman file, particularly FBI correspondence between Atlanta and Washington headquarters between June 9-June 13.

Read more about the James Brazier case

The day Dawson Police Officers Weyman B. Cherry and Randolph McDonald arrested James Brazier, seemingly without warrant, was not anomalous

| By Dania de la Cruz | Only four months into his lifetime appointment as a federal judge in Southwest Georgia

| By Nicole VanderMeer | Deep into the second day of Hattie Bell Brazier’s lawsuit against the law enforcement officers she

| By Christa Nutor | Hattie Brazier was a seamstress, wife and mother of four children who, through a series of violent